A team led by Michelle Comber, an archaeologist with the National University of Ireland (NUI), Galway, made the discovery as part of the Caherconnell Archaeological Project. Built in the late 10th century, the settlement remained in use through the beginning of the 17th century, housing a succession of wealthy local landowners. While most evidence of early literacy in Ireland comes from sites connected to the Christian church, the cashel, or ringfort, was a secular institution, reports Shane O'Brien for Irish Central. Its residents built their wealth through farming and trade.

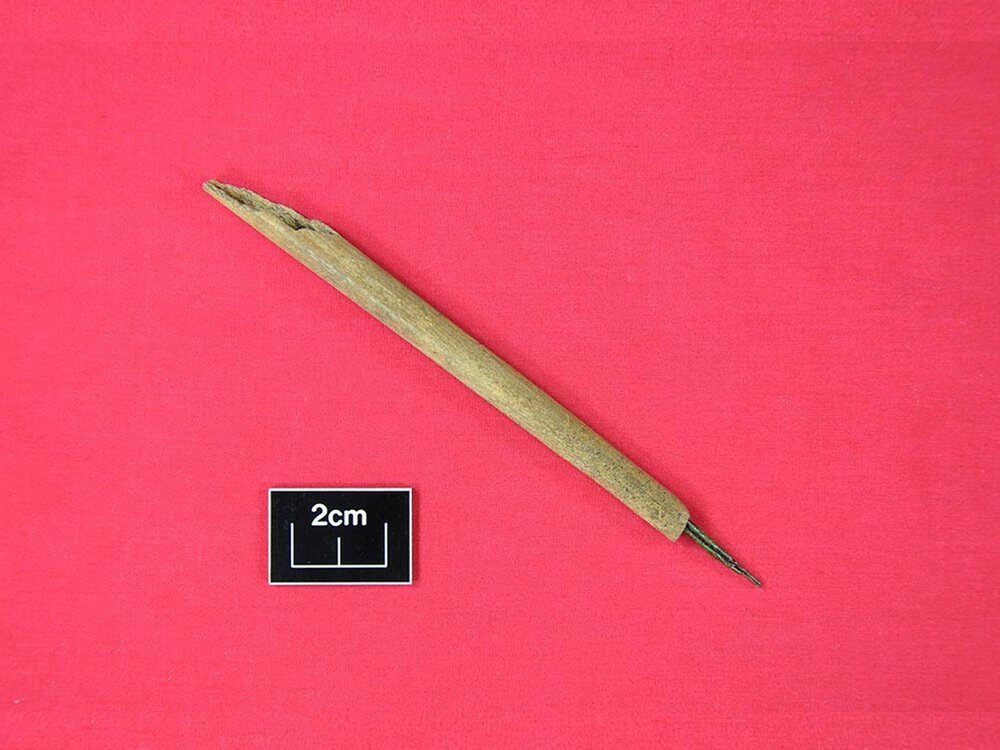

The pen's construction is distinct from the feather quills more commonly used by medieval Europe's literate minority. Historian and calligrapher Tim O'Neill notes that it may have been used for drawing fine lines, which would have been more difficult to produce with a standard feather quill.

"It would have worked well for ruling straight lines to form, for instance, a frame for a page," he says in the statement.

Though the artifact is the earliest complete example of a composite pen found in the British Isles, researchers know of both older and more recent related designs. During the Roman occupation of Britain (roughly 43 to 410 C.E.), people sometimes used pens made entirely of a copper alloy. In England, archaeologists have also found both copper-alloy nibs without bone barrels and vice versa. These specimens typically date to between the 13th and 16th centuries.

The unusual find at Caherconnell led the team to question whether the artifact could have actually been used for writing. Adam Parsons, an archaeologist with Blueaxe Reproductions, which specializes in creating copies of historic artifacts, constructed a replica. Testing confirmed that the object would've worked as a dip pen.

Comment: Blueaxe Reproductions demonstrates with a reproduction (due to the artifact's fragility) using a period-authentic ink preparation:

Caherconnell Cashel is part of a region known as the Burren along Ireland's western coast. Excavations at the site have uncovered not only remnants of the medieval settlement but also artifacts dated to as far back the Neolithic period.

"The excavations are beginning to build a picture of how life developed in a part of Ireland largely uninterrupted by intrusive groups such as the Vikings and Anglo-Normans," notes NUI Galway on the Caherconnel Archaeological Project's website. "The richness and excellent preservation of the archaeological record in this area hold enormous potential."

Archaeology Ireland magazine published a full account of the pen's discovery in its winter 2021 issue.

According to Colleen Thomas of the Library of Trinity College Dublin, writing was an essential aspect of monastic life in early medieval Ireland. Scribes trained by copying their mentors' work, inscribing words into wax tablets with a metal stylus. Eventually, scribes graduated to pen and parchment, using feather quills to copy existing devotional texts or author their own.

Livia Gershon is a daily correspondent for Smithsonian. She is also a freelance journalist based in New Hampshire. She has written for JSTOR Daily, the Daily Beast, the Boston Globe, HuffPost and Vice, among others.

It's a cleansing exercise, history is being erased and if it was me, I'd ban them from setting foot on such grounds.