The petroglyphs are now in different countries but in fact are only about 20 kilometres part.

The drawings were mostly found in the 1990s and early 2000s but many questions at the time remained unanswered.

In particular there was a dispute between experts as to whether the drawings showed extinct woolly mammoths that one roamed these parts - or fantastical creatures with trunks.

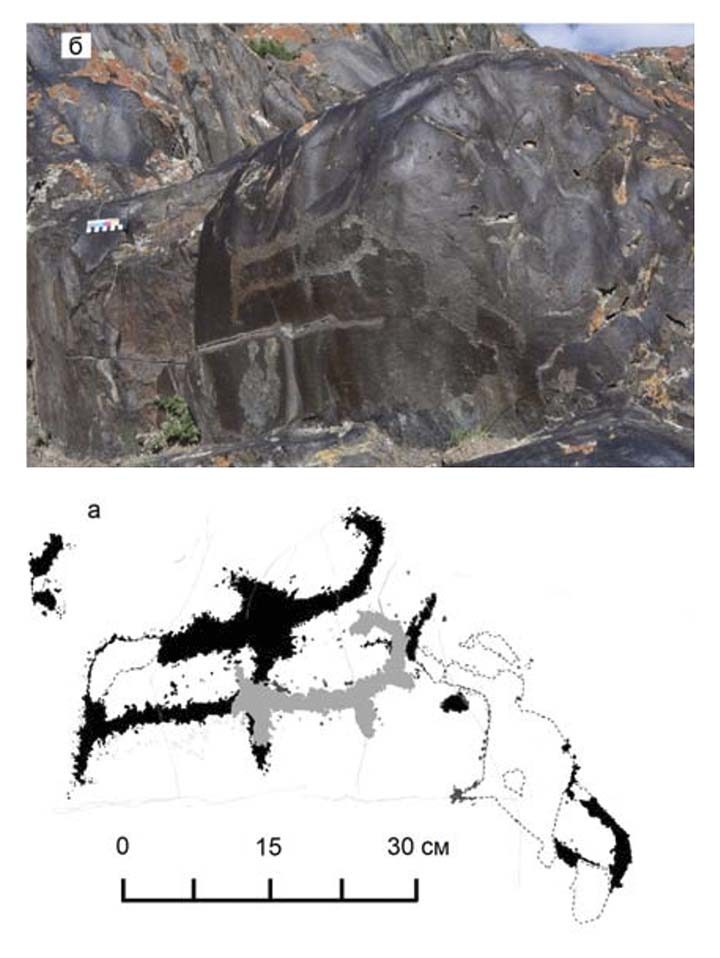

A new study by Russian and French researchers found new petroglyphs which helped the answer this conundrum.

Comment: Most likely this was a hairy Rhino, not woolly: Of Flash Frozen Mammoths and Cosmic Catastrophes

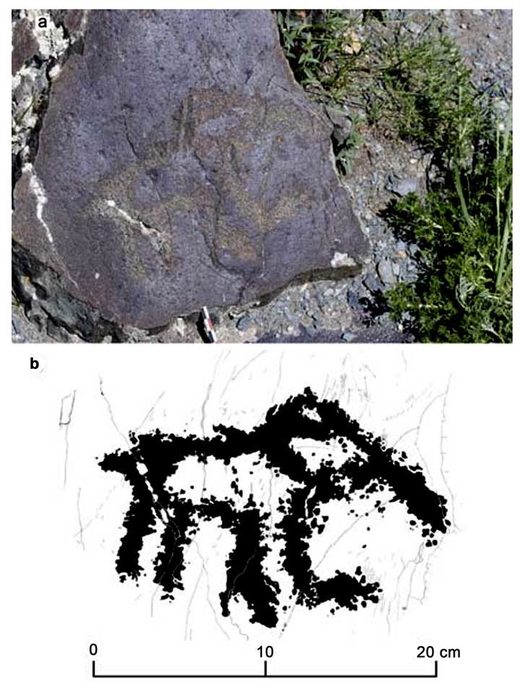

Most of the image is lost due to a rock slicing, but the animal is quite recognisable with an elongated, squat torso, short powerful legs, a characteristic tail, and an elongated muzzle with exaggeratedly enlarged two horns.

This was useful because these animals - like mammoths - became extinct around 15,000 years ago in this region, making the drawings the work of Palaeolithic artists.

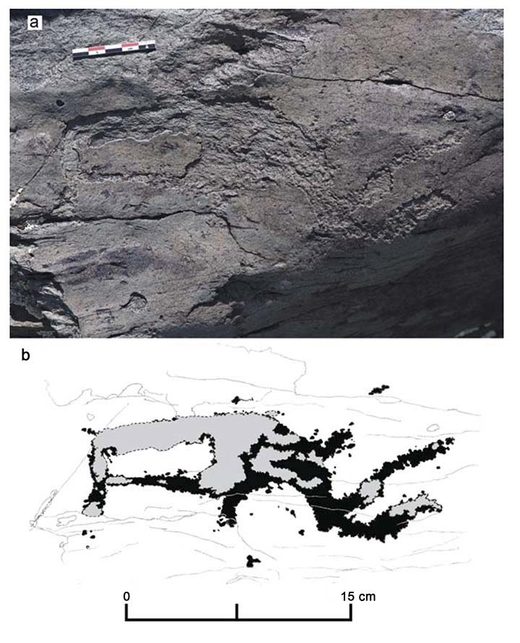

Another new image at Baga-Oygur III evidently shows a mammoth calf.

The scientists also concluded that the artists worked with stone implements, and not metal.

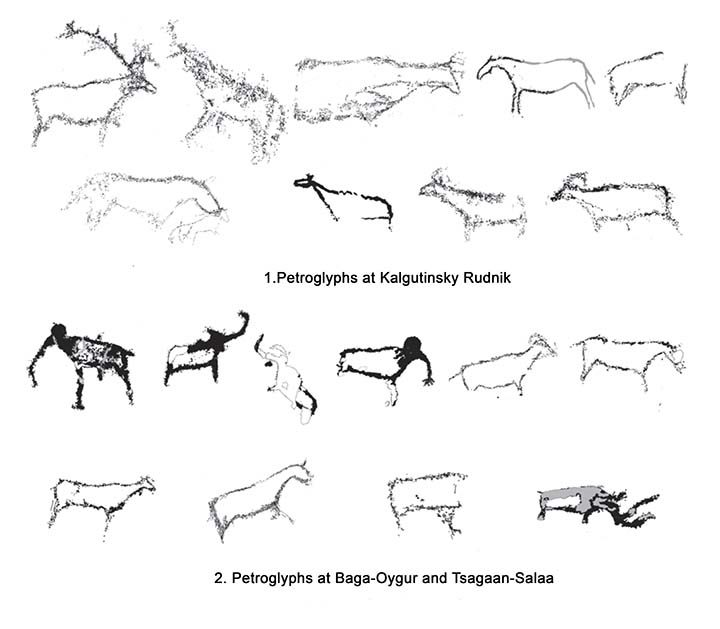

Stylistic similarities between the Mongolian and Siberian petroglyphs further indicated the Ukok drawings to be woolly mammoths.

They made their petroglyphs in the so-called Kalgutinsky style.

The experts concluded: 'We attribute the petroglyphs to the Final Upper Palaeolithic because the examples with typical features of this style depict the Pleistocene fauna (mammoths, rhinoceros).

'These stylistic features find their parallels among the typical examples of the Upper Palaeolithic rock art of Europe.'

Russian scientists Vyacheslav Molodin said: 'This is a new touch to what we know about the irrational activities of ancient people in Central Asia.

'This is the famous series of sculptures in Malta in Irkutsk region, whose age is from 23,000 to 19,000 years ago, and several examples from Angara.

'The assumption that the Pleistocene inhabitants undertook rock art on open surfaces fits into this context.'

Their article 'The Kalgutinsky Style in the Rock Art of Central Asia' was published in late 2019, in the magazine Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia (issued by Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography SB RAS).

Comment: See also:

- The Seven Destructive Earth Passes of Comet Venus

- 45,000 year old lion statuette found in Denisova Cave may be world's oldest

- Earliest known cave art by modern humans found in Indonesia

- Mysterious 25,000-year-old circular structure built from bones of 60 mammoths discovered in Russia's forest steppe

- Depicting plasma? Ancient 'mantis-man' petroglyph discovered in Iran

And check out SOTT radio's: