Today on MindMatters, we take a look at some of the basics of Stoic cosmology, how it informs their ethics, and the role it had on early Christian theology, specifically in the letters of Paul. For Paul the Holy Spirit actually has more in common with the Stoic Divine Pneuma than you might think, and has some far-out implications for what Paul thought about things like the "resurrection", "pneumatic" bodies, and the growth of knowledge and being.

Running Time: 54:53

Download: MP3 — 50.3 MB

Books mentioned in the show:

- Sellars's Stoicism

- Engberg-Pedersen's Cosmology and Self

- Irvine's Guide to the Good Life

- Ouspensky's In Search of the Miraculous

Harrison: Welcome back to Mind Matters everyone. I hope you tuned in last week to our show on breathing as we introduced the topic of today's show. Last time we were talking about breathing exercises and then got into just a little bit of the theory behind them. For example in practices like chi kung where the breath is actually seen as containing or being equivalent in some way to force or energies of some sort or another.

So we hinted at the vast multitude of belief systems and world views in which spirit or the breath is fundamental in some way. One of those systems which we're going to get into today is Stoicism. Just as a brief background, Stoicism probably isn't what you think it is. A common misconception is that the Stoics, who were an ancient Greek philosophical school and then a Roman school as well, are or were what we now think of as Stoic, stiff upper lip, bottled up emotions, like the Vulcans of the philosophical tradition. In fact that's not really what they were about at all. We can't project back our meaning of Stoicism onto what they were actually all about.

You can get an idea of what they were all about by reading someone like Marcus Aurelius who was a Roman emperor and a Stoic. His book Meditations is his meditations and thoughts on observations of life and his place in life and how he approached being a human and being an emperor and applying the philosophical principles from Stoicism in his life.

Along those lines, next week we're going to be discussing that aspect of Stoicism, the practical art of living as they called it, so if you want to get into the practical side of things I'll just give a hint for next week and that's this book, for example. There's a ton of them. Stoicism has experienced a resurgence in the last 10 or 20 years. This is one of the most well-known books by William B. Irvine, A Guide to the Good Life. This is almost exclusively dedicated to the practical aspects, the actual exercises and practices that you can put into practice in your life to be a better Stoic.

But the aspect we're going to be talking about today is more the cosmology, what the Stoics actually thought about the nature of the world, the nature of reality because like many philosophical systems, and especially the Greek ones, they were an entire system. They had a cosmology that went along with their practice. For the Stoics they placed a great importance on cosmology and also logic and practice and ethics. Depending on which philosophical school you're looking at you might find different emphases placed on those. The cynics for example, didn't place much value at all on the cosmology or philosophizing. They were purely in the practical mode. Then you had something like Plato's academy that was more focused on the theory, the philosophizing, and less worried about the actual implementation of those principles in daily life.

The Stoics, I think, had a more balanced view of the theory and the practice because the two were important but they also supported one another. So the practice came out of the worldview. It was grounded in the worldview. That's what we're going to be focusing on today with the previous show on breath and breathing as a launching point because for the Stoics, they were materialists and monists and what that means is that they weren't dualists. They didn't think there were two types of fundamental stuff in the cosmos. They thought there was one fundamental type of stuff and materialists because they saw the entire world as being material in some way or another.

So it wasn't like there was a transcendent other worldly god or realm of forms or something like that, that had formed the world. It was all a gradation of one thing from the lowest to the highest. It was a complex world view. It wasn't materialism as we think of materialism today where you have one stuff and that's it. The modern materialist worldview is that we have one stuff, what we think of as matter, the physical things that make up the world from subatomic particles and that's it. The hard core materialists today reduce everything to matter whereas for the Stoics there was one thing - matter, but it manifested in different ways, in different degrees. So you did have such a thing as mind but mind was a finer gradation of the primal stuff that made up inorganic matter.

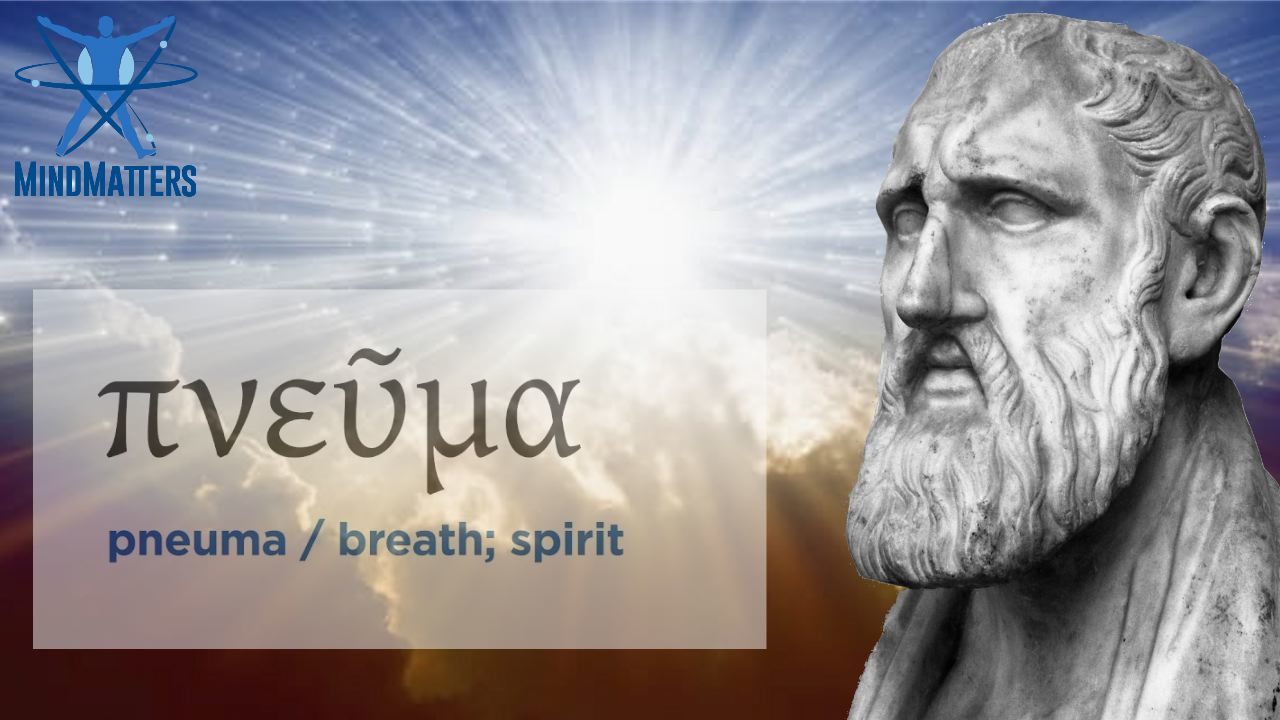

Now the substance that they identified as this fundamental stuff was what they called pneuma. That's the Greek word for it. We might say pneuma as in pneumatic, like pneumatic tubes. It was spirit or breath. Right away there's a correspondence with early Christian tradition because in the earliest writings of Christianity and the letters of Paul he repeatedly refers to the pneuma. That would be the holy spirit or the spirit of life, spirit of god, spirit of Christ and the spirit among everyone. There's spirit stuff all over early Christianity and the worldview at the time, the way of looking at the world and thinking of the makeup of the world was arguably predominantly Stoic at that time. At least that's the argument of one of the guys that we'll be talking about whose book we'll be looking at a little bit today.

So there was this stuff that made up the universe and everything in it, this pneuma, this breath, this spirit and that was actually a later development of Stoic thought because early on, the primary element was seen as fire and it was later on that it got adapted to air. So pneuma was perceived and thought of as a fiery, airy substance. It was warm, it was hot, it was breathy and essentially equated with the spirit or breath of god because the Stoics were not materialists in the sense of everything is just matter. It's a more complex materialism. They did believe in a unitary, original, fundamental consciousness or agency but it was more like the panentheism of Griffin and Whitehead, that the universe is inside the mind of god and the mind of god is inside every bit of the universe.

Carolyn: So it's the embedding matrix of everything that is.

Harrison: Yeah. And from this, everything comes out of it. So the qualities of this pneuma are intelligence, reason, logos, logic, the original word that you find in the gospel of John. This pneuma, like I said, is in various gradations so you have these almost like phase changes in this cosmic substance, this cosmic breath. So the breath exists in these various levels of what they call tonus or tension.

I don't know if this is exactly how they'd phrase it, but when reading the concepts, this is the picture that develops in my mind. The most tense would be the very basic matter, the lowest form of pneuma and then above that the pneuma takes a different tension and that would be the animating soul, the psyche which animates all organic beings. So you can have animals and humans would share this soul level pneuma. Then when you get to humans you have a further gradation of pneuma which is pneumos, the mind. This is where you actually get the ability to reason about things, to be a rational being. Then above that you'll have another level. That would be more like the divine mind or divine pneuma.

One of the descriptions of why they thought of pneuma as fiery is that in that worldview, in that philosophical system, the gods were equated with the heavenly spheres. So they saw stars and planets, the sun, comets, all of these things were heavenly spheres and identified with beings. All of these heavenly objects were beings or agents of some sort. They had mind. So the heavenly bodies, the highest level of beings that were observable were these heavenly bodies so that was the stuff that made up their bodies. It was pneuma. They were made out of this fiery, airy substance.

So that would be a level above the human level of pneuma. Because it was so fundamental, there's all kinds of different directions you can go in with looking at this pneumatic way of looking at the world. But just to tie it in to start out with, with our show last week, this is the point we were making, that for the Stoics, the fundamental thing about reality is breath in some sense, that the human mind, the human organism is somehow infused with this universal cosmic breath, energy or life force. It's hard to say whether there was a transfer of traditions and knowledge between cultures that led to this kind of almost universality of the view of breath being so important, or if it was just a spontaneous development of similar systems.

Maybe it's just because air is so universal. Everyone breathes. So similar beliefs cropped up in relation to air because air is so important to life, but with this extra something added to it because air isn't just this gas that you breathe. There's something more to it that gives it an added significance or importance.

Carolyn: Well the fact that it sustains life. You could say air in the form of wind has certain effects. I'm sure they made some connection between that and weather. But this extra added component, air, when added to a living body is what sustains it because if you took the air away, the living body doesn't live anymore.

The other thing I thought was really interesting is that they already had the concept of this pneuma being cyclical, that it went back and forth between its generative ground and its manifestations which I thought was pretty cool because that's actually usually thought of as an eastern idea. So somehow that made it across.

Harrison: They were some of the early catastrophists of their kind, right? They thought that the world and the cosmos went through periodic destruction and creation and that this was pneumatic in nature. So eventually the time would come when the world would be destroyed by pneuma, by fire, by this fiery cosmic substance and that's the cycle. So you've got the destruction and then the rebirth, like a phoenix.

Carolyn: Well they didn't consider it a bad thing. It was just that all things were gathered back into the primal pneuma and recreated again.

Corey: Another important connection - and correct me if I'm wrong - was that the Stoics connected the pneuma and the logos together in a very important way so that along with breath there's also the word and with the word you have intelligence and rationality and some higher divine force that's taking place and working throughout the entire cosmos. So I think that's a principle reason why, when you're studying Stoicism, it's so important if you're studying the practical stuff, to study their worldview as well because it all fits together in a very important way. You have to have the highest thing to aim for. You have to have this god-like being really, in order to make sense of all these other aspects and to understand why is there this rational force in the cosmos, what is its place and what is your relationship to this rational force and what ought you to do with this knowledge. That's where the practical stuff takes place. But as you're saying, it all comes back to their view of the universe as a biological organism, which is one big difference in the kind of brands of materialism. Theirs' isn't a mechanical materialism. It's a biological materialism.

Harrison: It's organic.

Corey: Yeah, it's very organic. The universe is a living thing and you are part of it and all of their ideas of fate and the cyclical things, they all come out of this really critical idea.

Harrison: It's like I said at the beginning. The theory is integrally tied with the practice. Before I get into that I want to point out that the Irvine book that I mentioned before is purely practical. It's more like a modern self-help book but based on early Stoic ideas. But if you want an academic introduction to Stoicism and all the nitty-gritty, sometimes boring but other times interesting ideas involved, this one's pretty good. It's Stoicism by John Sellers. It's an introductory textbook that goes over all of the basics including their logic, physics, ethics and associated ideas.

One really interesting portrayal or way of describing that link between the theory and the practice is actually by a New Testament scholar, Troels Engberg-Pedersen. He wrote two books on Stoicism and its relation to early Christianity. He also wrote I think a couple of books strictly devoted to Stoicism and his interpretation of the main ideas of Stoicism. This is the book that we'll be mentioning today. It's called Cosmology and Self in the Apostle Paul, the Material Spirit.

He's arguing that there is a fundamental Stoic cosmology at the root of the letters of Paul. But the idea that he developed in his other books, the one he devoted strictly to Stoicism and the book he wrote before this called Paul and the Stoics, is the idea that because of the nature of the universe, because there is this universal stuff that the universe is made of and that is essentially the mind stuff of god, that that is logos or reason, that there's something fundamental about intelligence and specifically divine intelligence and it's that intelligence that infuses and is a spark in every human being.

So the process goes something like this. If a person comes to realize that they are a spark of the divine, that they have divine reason within them, then that understanding then creates this closer identity between them and the divine reason and now if they understand and feel and experience that identity with the ultimate, the unifying principle and being of the universe, then they can't but act rationally. It has this transformative effect and that is the goal of Stoicism, to reach the ideal of the level of the Stoic sage. At that level the Stoic sage is an austere but joyful sage-like being who always does the right thing because that's essentially what the goal is - to learn what the right thing is to do in every situation and to do it.

Carolyn: Also part of the practice, although they never used the word, seemed to be an alignment or an attunement, that the more you embodied these principles of order and balance and recognizing the cyclicality of your life - you have good times, you have bad times - and modulating your response to them, you would enlarge your ability to be a receptacle of this pneuma.

Harrison: There's a connection, a pull towards the logos that transforms your mind and therefore your behaviour so that you become a Stoic sage that is an exemplar who is always doing the right thing. Then after that, an implication of that new state that you find yourself in is that you are now identified with all of the other rational beings around you. So you become almost a member of this new club of rational beings who act well with each other or towards each other. It's a new club. {laughter} Cosmopolitan - they are citizens of the cosmos, right? So there was this community element to Stoicism and that determined your interactions with other people, the way you lived with other people and the way you behaved with other people.

There was almost like a religious transformative aspect to this philosophy that had certain implications for how to behave in the world. Because everything was one cosmos, there must be right ways and wrong ways of doing things. When you were doing the right thing they'd call it something like "in accordance with nature" or something like that. There was acting according to Nature. If you were acting according to Nature, you were acting rationally and doing the right thing. And doing the right thing looked a particular way. There were certain things you just did and certain things you didn't.

Carolyn: This would be nature with a capital "N".

Harrison: Right.

Carolyn: As opposed to the lion out on the plain eating something, was acting according to nature, but as a rational human being you probably didn't want to do that. So there was a higher order. Also I would say too that they felt it incumbent upon themselves to be acting out the divine reason. If you want to go off into Jordan Peterson territory it's probably where he got it - that it was their duty to enhance the order of their environment by acting well, by being an example, but creating a higher level of interpersonal actions and how you behaved within the world, but that you would show a better way to be.

Corey: I just want to interject quickly and say that a lot of the Stoics were unsung heroes of unbelievable character, intelligence and wit. In the history of western philosophy they get lumped together but there was a lot of debating and discussion and none of them considered themselves slaves to the founders or to the ones who systematized logic and that there's this general aura that they had a stale system that was based off of Aristotle when in fact their logic was quite different from Aristotle's. From my reading in the 20th century it sounds like logicians rediscovered their work with new eyes when they discovered the propositional calculus and realized that they were onto a completely different track of logical thinking that was quite novel for the time. It was a huge step forward and it wasn't like the syllogism of Aristotle which has been criticized for a number of reasons which we won't get into here.

But they had a much more action-oriented and practical and even in some cases, Boolean. It sounds like you would probably be writing some of their logical codes in your coding software, rather than Socrates was a man, type stuff. But they're really unsung heroes of our history and have made a huge impact that is far greater - as you're suggesting Harrison with the connection to Paul - than just the idea of having a stiff upper lip.

Harrison: That's one of the remarkable things about the legacy of Stoicism, is that most people don't realize it. Even philosophers don't realize it. This guy William Irvine, in the introduction to this book, he gives a bit of his story and how he discovered the Stoics. He's a philosophy professor and didn't know anything about them for the majority of his professional career because his professors hadn't assigned any readings of the original Stoics so he had the idea that they must be like everyone else thinks Stoics are, just these stiff upper lipped type guys. So finally he was reading a novel by Tom Wolfe where one of the characters...

Corey: A Man in Full I think.

Harrison: Yeah, one of the characters encounters the Stoic writings and then starts spouting off Stoic stuff throughout the novel and that intrigued him so he started reading him and essentially converted to Stoicism after that, after an investigation and became a practicing Stoic. He wrote this book as a Stoic guide because one didn't exist until that point. He wanted to make a modern-day 'how to be a Stoic', how to implement Stoic ideas and practices into your daily life. It's just remarkable that such an important and interesting system with so many branches and tendrils into our intellectual history and cultural history, especially through Christianity, that it is not realized and talked about and more widely accepted.

Carolyn: I think different portions of the elements that eventually have culminated in our society grabbed different pieces of it. So they've come in piecemeal, but never presented as part of the original system they sprang from. We can blame Paul for some of that. {laughter} Or thank him.

Harrison: Well getting to Paul, that's one of the interesting things. Because we don't have this conscious awareness of what Stoicism is and how it might apply to certain things, then when we read a text like the New Testament, we miss out on what it's actually saying. So that's one of the really interesting things about Engberg-Pedersen's work. He lays out some of the Stoic ideas and then shows how they're right there on the surface in these early texts. By just engaging in that procedure, that exercise, you see that some of the things that Paul was saying were really weird, way weirder than you might think that Christian theology is in the first place, almost like sci-fi levels of weird. {laughter} There's some really strange and fascinating things going on there.

For instance, I mentioned that the heavenly bodies are made of pneuma. In Paul's letters, Engberg-Pederesen shows that you have the same idea there, that Paul talks about the heavenly bodies. He talks about the stars and their different glories for different levels of things. A man has his type of glory. A star has its own glory but that the community of Christians will become stars in the sky. They will become, somehow literally, stars in the sky. And by putting together these texts, the picture that forms is that through some process, the Christian community will actually acquire heavenly bodies for their own. They will inhabit heavenly bodies.

So what's going on is that the body of flesh is slowly dying. It's an entropic, deathly thing that is decaying and within that decaying body is growing and filling up those decaying spaces with heavenly pneuma. So a new spirit body, which is a pneumatic body, is being formed within Paul himself and within these early Christians and creating what will be their resurrection body, as it might be called, but it's actually a body composed of pneuma, composed of this different type of stuff. We have all these ideas in mainstream Christianity but also new age religions about the astral body, the spirit body and things like this. But when you hear it or read it stated in such basic terms, it's very strange. It's this actual body being...

Carolyn: Regenerated.

Harrison: ...grown and generated out of this divine fiery plasma stuff that is then inhabiting the space that has been lost to the decaying parts of the fleshly body and that at the time of the parusia, the coming of Christ, the resurrection, whatever that is, that the whole world, like with the Stoics, is going to experience this transformation into heavenly pneuma, into god's pneuma. So there will be all the fleshly parts, all the parts that don't have that initial portion of spirit to sustain them will be burned away. So all the fleshly parts will be burned away but the body that has been generated within that old body will be the one that lives on and lives in this new world, this new pneumatic world. Like I said, it's far out stuff. It's pretty trippy.

Carolyn: Well the thing is too, Paul obviously had an extraordinary experience of some sort, life-changing down to the soles of his feet. In one sense he may have been taking the concepts that he could grasp them under and expressing it.

Harrison: Yeah.

Carolyn: But on the other hand, I've been going through this book too and he's pretty, pretty clear that this is the process he thinks is going on.

Corey: Well Harrison, you also like to tell a story about how Paul thinks that he interacts with that with the congregations too, right? How his own pneuma interacts.

Harrison: For Paul, his experience with the risen Christ, whatever that was for him, gave him a portion of the divine pneuma, of Christ's spirit, so literally a portion of Christ's mind/spirit inhabited Paul, entered his body in some way and is now growing in his body. So for Paul, his missionary activity is to now dispense with and disperse this pneuma, this spirit, to other people. Basically through his speech and through his letter writing, what Engberg-Pedersen calls bodily practices, they're practical behaviours and actions that Paul takes to transfer the spirit from himself to others.

You could think of it in terms of the last supper, the dispensing of the body of Christ because the body of Christ is the spirit of Christ, this heavenly pneumatic stuff, the feeding of the 5,000. You could look at a lot of the parables in the gospels as symbolic representations and metaphors for this giving out of the spirit.

You mentioned something earlier Corey about the logos and the importance of the word. If you think about it in terms of this worldview, the air is what passes through your throat to produce words. So there was something pneumatic about speech because the air was what produced the words that came out of your mouth. So this intelligence in your throat was something divine. This was the expression of the divine through your body. So for Paul, when speaking the truth, that spirit went outside of his mouth with his words and entered into the ear holes of the people listening and gave them a bit of spirit to then form within themselves and that sharing of the spirit among all of these people tied them all together, essentially gave them a portion of the same mind.

So that's where the idea of the body of Christ comes from. The body of Christ is the church. They are all sharing in something. They all have access to this higher mind of which they are appendages. What was that Netflix show that the Wachowskis did? Sense8?

Carolyn: Sense8.

Harrison: The idea of this shared consciousness.

Carolyn: Not only was he broadening the reach and strengthening this pneuma, he also at one point says to one of his congregations - I think it was to the Philippians - that you are sustaining me, so that they were doing something that they could give back to him, strengthening pneuma.

Harrison: Right. If you read Paul's letters they're very emotional.

Carolyn: His purple prose.

Harrison: Engberg-Pedersen ends the book in a nice way. Let me see if I can find the last paragraph there. I'm going to read the last paragraph, just to get to the last sentence because it kind of captures what it's like to read Paul's letters. I'll start with the sentence in the second-last paragraph.

"So Christ as a shape in the Galatians, we know what Paul has in mind, that the pneuma might once more be found in them as transmitted to them by Paul's own letter."

So again, this is the practice of transmitting his pneuma to them through his letter writing. But he goes, on,

"However, just as we took it to be the case with Paul's concrete cosmological conception of the resurrection, so here too we cannot make his understanding of the concrete pneuma-transmitting character of his letter writing our own."

What Engberg Pederesen's saying is that he doesn't think that this way of looking at the world is applicable to modern humans because we don't see the world the same way so we can't adopt that idea as our own. That's debatable because he's coming from a modern scientific perspective. He's right in the sense that the wording and stuff is out of date, but I'd say that there's probably more truth behind it than a modern academic is willing to give to it. But anyway, with that in mind he says,

"None of us could conceivably believe that we would be actually sending our pneuma to somebody else by means of a letter. Perhaps though, if this was Paul's own conception, we can better understand why the Pauline self, his converted self merging into his apostolic self, feels so strongly present in his letters. His theory of his own letter writing may well have contributed to a style of writing that made that self be most vividly present. One feels that he is almost there."

So that's how he ends the book and it's pretty appropriate because there is a presence when you read Paul's letters that's just like he's bursting out of the page at you. Maybe there's something to it. What is it about something that does that, that captures people, that grasps you? You read an idea for the first time or you have an experience with a person or they tell you something that just goes straight through your ears into your heart or your soul, that deepest recess, that part of yourself, what is actually going on there? Well the Stoics tried to give an explanation for what that is. That is actually some process happening. There is something about the thing you're hearing that is changing you, that is affecting you in a fundamental way. Maybe it's not exactly as they described, but maybe there's actually something to be gleaned and learned from that description, from the imagery that they have of it.

One way of looking at it in a modern sense would be in terms of information. I don't really like that way of looking at it just because the word itself, information, is so dry, bland and boring. I much prefer 'heavenly pneuma'. {laughter}

Carolyn: I was just thinking information is very dry and maybe on some level Paul knew that. His letters are very emotional and that is a way of cutting through. He doesn't denigrate the intellect but it does cut through and create those resonances that allow you to absorb the information.

Harrison: Yeah. There's something about the truth when you hear it, for instance, that hits you in a certain way. I want to tie this back to the breathing exercises. I'm not saying that the Stoics had it all right or that this is necessarily an accurate description of the way the world is, but just to picture it to yourself, even just because it's interesting, but also because there may be truth in there that is hidden beneath the surface in some way. But you have this spirit that is transmitted through speech or writing and it's associated with the breath and the air. This is one thing that Gurdjieff put into practice. I mentioned Gurdjieff last time when we were talking about breathing exercises because one of the things Gurdjieff did - he too had his system, his theory but he also had the practice of it and the practice doesn't get talked about very much because for the longest time it was kept secret by the people who were familiar with him and the school that built itself after his death.

But the famous book, the one that most people who are familiar with Gurdjieff know, is In Search of the Miraculous by Ouspenski, that pretty much lays out all the theory. But it was only in the last 15 years of Gurdjieff's life that he put it into practice and that we have accounts of how it was put into practice. There's a little bit of that pretty obviously hinted at, we'll state explicitly but you have to be kind of aware to realize that's what's going on, in his last book Life is Real Only Then When I Am where he gives a breathing exercise. And in that breathing exercise, the way he lays it out is that - skipping all the details, you can read that book and find the exercise for yourself - but tying that into his theory, what's actually happening is by consciously engaging with the breath, so observing the breath, essentially breathing consciously, what's happening for Gurdjieff in his system is that you're breathing in what he called active elements or higher energies or hydrogens as he called them.

There are these energetic particles that are in the air and by conscious breathing you are digesting then, these elements, these particles that otherwise just get expelled and not used and these particles, these higher hydrogens, these active elements are actually what creates what he called the higher being body or the spirit body. So when you're doing conscious breathing, for Gurdjieff you're actually digesting the material that will then create your pneumatic body, that will then be able to survive death. But you won't have that body if you don't grow it and you won't grow it if you don't do conscious breathing exercises.

So again, Paul read in the Stoic light is pretty far out and Gurdjieff just read in a Gurdjieffian light is far out because they're both characters. I'll say that. They're both quite creative, is the way to put it. {laughter} So for Gurdjieff, these active elements, mixing the systems a bit, this spirit that you breathe in then gets digested by these processes in the body that creates a double body, a new body that will, like I said, survive death because for Gurdjieff you don't automatically have a soul. When you die, if you don't have a soul then you're going to disintegrate in some way and probably never come back. If you have the seed of a soul, the embryo of a soul, you might come back and reincarnate and suffer a whole lot until you learn the lessons, until you finally learn how to grow a spirit body and only then when you have a fully developed spirit body, which is associated with what he called having a real I, so not the fake personality I that we have, the ever-changing sequence of personality fragments that we have within ourselves that govern what we do, but when you have our own solid, unified self, that self then has the ability to consciously either incarnate or go on to other worlds or who knows what.

But all these systems come down to this mystical quality to the air that we breathe and that has the effect of re-enchanting the world. This is an observation that several theologians in the 20th century have made, which led to David Ray Griffin writing one of his books. I believe it was called The Re-enchantment of the World or something like that. The world is pretty boring. There's not a lot of spirit in it when you look at the modern scientific worldview. There's not a lot to inspire those...

Carolyn: No art or music or anything that's really worth listening to or looking at.

Harrison: Right. And even then, something more than that. Even though we live in this world with this scientific worldview, we all have the emotions that come when we listen to music we enjoy or watch something moving that we see on TV or in a movie. But there's another level of experience or feeling or that search for something higher. Ouspenski called it miraculous in what became the title of the book. That's the search for something extra, for something more.

Carolyn: That gives meaning.

Harrison: Yeah, that gives real meaning.

Carolyn: One thing I found kind of interesting about the Stoics is that even though there was this idea of assimilating more pneuma and aligning and acquiring this body that will survive the conflagration, the gathering in and redispersing, it didn't seem to be something that exercised them. They didn't seem to be frantic or worried about it. It was just sort of, "This is what you do if this is something that interests you'. They weren't out proselytizing that 'the world is going to end and you have to do this'. They seemed to be rather calm about it all.

Harrison: That comes down to the Stoics theory of emotions, right? Their psychology, which we'll get into in our next show because a Stoic doesn't worry about things that they have no control over. So if the world's going to end tomorrow it's not going to bother them because they have no control over it. {laughter} It wouldn't be rational to fear something that you have no control over so just get on with it. Meet your death joyfully, basically. How are we doing for time? Where are we at?

Adam: 46.

Harrison: Okay. Do you guys have anything else to say?

Corey: Yeah. I would just say if there's one thing I would hope that everyone takes away from this show, it's that Stoicism is part of a tradition that goes back years and years and years and years but we can point to probably students of Socrates, people who are impressed by Socrates and his death, his sacrifice and other brilliant individuals and that has continued on and inspired the early Christians and that continues to this day to inspire and to offer solutions to extraordinary problems and that it's something worth investigating. I would definitely highly recommend investigating the systems, the ethics, the logic, the physics of Stoicism, just as a way of connecting to that tradition. And if there is still some pneuma left within it, of gathering that for yourself.

Harrison: Well I was thinking about reading a short bit to close out the show. In this book Engberg-Pedersen gets into what Paul must have meant by such things as faith and faith's relation to knowledge and what he actually meant because in most modern Christianity, the idea is that you just need to have faith in Jesus, and that means that you'll be saved or that you are save. But first of all, is that actually in Paul and what does that actually mean?

So for Engberg-Pedersen, when he's looking at this from this Stoic perspective, there's a much higher emphasis placed on actual knowledge and understanding. It's not like you just believe in something blindly, but that you actually understand something and the root of faith is that understanding. So I'll read a paragraph and a few sentences that just say this in his own words.

"Very importantly, the texts are speaking of how those human beings have acquired knowledge of God, or Christ for the Philippians. The theme is one of cognition, of the acquisition of knowledge. Paul is speaking of the way in which, in conversion, his addressees and he himself have come to know God as a result of God's knowing of them at that very moment. We may suppose that he is relying here on what, in modern philosophical terminology, has become a distinction between two types of knowledge - knowledge by direct acquaintance and propositional knowledge or knowledge 'that'. Something is thus and so. His idea may be that in conversion human beings have acquired propositional knowledge of what God is based on direct acquaintance with God. Moreover, a kind of acquaintance that has been brought about by God himself."

I'd say that's the total opposite of what some modern Christians think of as the process of what's going on. It's that you believe and then hopefully you'll have some kind of epiphany, or you never will, but you believe in God so that kind of assures your spot in heaven. But for Paul it was the experience that came first. It was the direct acquaintance, the actually knowing God that then gave you faith. Because you understood something very basic about the nature of reality, that was the foundation of your faith. That's why faith was so strong because it was actually based on knowledge, not based on just believing something that someone told you.

A couple of other things:

"So when this knowledge on God's part is met by the chosen ones, the Christians, then they have the knowledge of God. In order for the kind of action that flows from this knowledge to be people's own and in order for them to be therefore also themselves responsible for their ways, the knowledge must be their own too in addition to having clearly been generated by God."

That's in the section on the idea of human agency and freewill. So for Paul he's not a strict determinist in the sense that God controls every action that people are doing. It's that there's this handshake that's going on between the higher and the lower, that the freewill, the agency of the humans, of the lowly creatures, is as important as the signal coming from above. It's where they meet that the higher will, becomes the will of the lower being.

So it's never that things are completely done for us. We're not just puppets of the higher power, it's that we actually, in this process that Paul's talking about, become more of a channel for that higher force to express itself through, but with our complete participation because it's based in knowledge and understanding.

Carolyn: He writes in another place too,

"It's obvious that the pneuma plays a crucial role in bridging the gap between God and human beings. The pneuma of God knows the depths of God and by receiving the pneuma that is from God, human beings obtain cognitive access to God's gifts. They now understand God."

Harrison: Mm-hm. And then one more to wrap it up:

"But the strong and exclusive emphasis on God's agency in generating the proper knowledge, must not be taken to obliterate the other results we have also reached, that the knowledge generated in this way in human beings by God, is also distinctly their own and indeed, when they do have this knowledge, then they are aligning themselves and of course also being aligned with God."

It's just another way of showing that it is a mutual process of the higher and the lower working together cooperatively and not the lower rebelling against the higher impulse and it's not the higher impulse controlling and directing the lower. It is a natural meeting of the two that, as the Stoics would say, would be in accordance with nature.

So, very interesting stuff. If you want to check that one out, it is Cosmology and Self and the Apostle Paul, the Material Spirit. It's a bit academic at times but interesting stuff.

Carolyn: He makes it very easy. He puts it in an academic format for his peers but it's not pedantic. In fact he even says, "I've done that deliberately. If you really want to go super dry university, go to the footnotes." They're crazy.

Harrison: Alright, with that said thanks for tuning in everyone and we'll see you next time.

Reader Comments

Second, Acts cannot be regarded as history. It is a novelization idealizing early Christian relations and written more than 2 generations after the events it purports to describe. Third, Paul most likely did reject Greek philosophers (though we can't take the word of Acts), but that does not preclude his use adoption and adaptation of what were at the time mainstream cosmological concepts.

Secondly, the book of Acts is a collection of eyewitness accounts beginning with Jesus's resurrection, and can be fairly precisely dated prior to the execution of Paul around 62AD. How do you get a later date?

What happens is that a word acquires certain connotations through theological interpretation. That interpretation then influences the translation, to the point where, in the case of justification, we get a word that doesn't actually capture what Paul is saying in the Greek. We can all read modern English translations, but every translation is influenced by the translators' own theology and interpretation. Sometimes they make good decisions, sometimes questionable, sometimes flat-out wrong.

For the spirit, it helps to know that when Paul was writing, there was a widespread understanding of spirit as a basic element of the cosmos, essentially a portion of the mind/reason of God. It was a physical stuff existing at various tensions, responsible for the inertness of inorganic material, the animating 'psyche' of living things, and the mind or 'nous' of humans. In its divine form it was the stuff that made up the heavenly bodies. So when Paul says believers would shine like stars, he meant it quite literally: the spirit in them was actually the same stuff that made stars. There's more to it, but the point is just that without an understanding of what people meant by the words back then, we risk projecting our own ideas, and other ideas from later periods, onto what was originally there.

As for Acts, see the work of, for example, Richard Pervo and David Trobisch. That's a good place to start, but there's more.