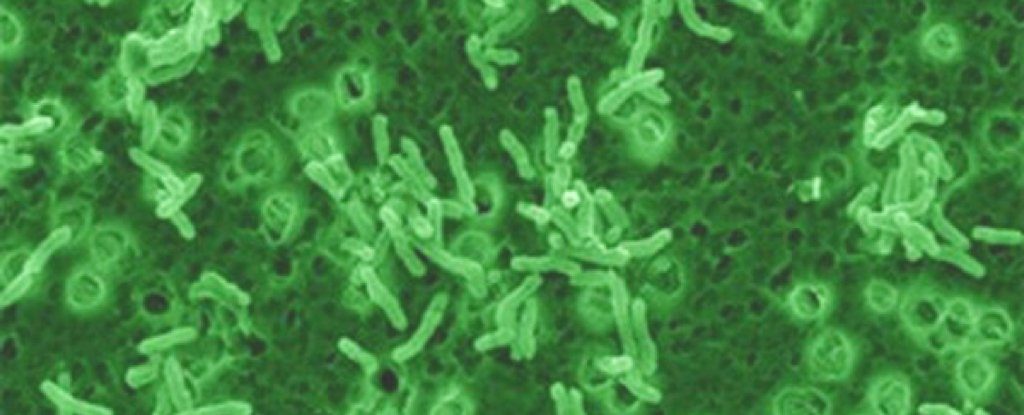

© Christopher LowryMycobacterium vaccae.

Scientists have isolated a unique molecular pattern that might one day enable a 'stress vaccine' to exist for real - and they found it hidden inside a bacterium that thrives in dirt.

Mycobacterium vaccae is a non-pathogenic bacterium that lives in soil, and has shown considerable promise in health research; now, a new study may have finally figured out why.

The findings suggest that a specific kind of fat inside M. vaccae could be why exposure to this seemingly beneficial bacterium in ground soil may be good for us.This work ties in with the idea of "old friends", a hypothesis that claims humans co-evolved with a bunch of useful microorganisms, and losing those ties in the modern environment has led to an increase in allergic and autoimmune diseases.

"The idea is that as humans have moved away from farms and an agricultural or hunter-gatherer existence into cities, we have lost contact with organisms that served to regulate our immune system and suppress inappropriate inflammation," says neuroendocrinologist Christopher Lowry. "That has put us at higher risk for inflammatory disease and stress-related psychiatric disorders."

Lowry has been researching

M. vaccae for years, finding in a

previous study that injecting mice with a heat-killed preparation of the bacterium prevented the emergence of stress-induced reactions in the animals.

But until now, nobody was sure what was it in

M. vaccae that could be responsible for such effects.

"One of the burning questions is, essentially, what are the critical components of the bacteria that seem to benefit the host?" Lowry told

The Denver Post.

In the new study, the researchers isolated and chemically synthesised a fatty acid called 10(Z)-hexadecenoic acid, which looks to be how the bacterium can reduce inflammation in other animals.At the molecular level, the lipid seems to work by binding to receptors called peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR). In doing so, it inhibits inflammation pathways - at least, in experimentally treated mouse immune cells."It seems that these bacteria we co-evolved with have a trick up their sleeve,"

says Lowry.

"When they get taken up by immune cells, they release these lipids that bind to this receptor and shut off the inflammatory cascade."

A lot more work would need to be done to see if the same effect could be replicated in humans. If it can, the researchers say this discovery could help eventually develop a 'stress vaccine' to help people in high-stress professions that place them at risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder.

That's still a long way off, as the research stands now. Lowry is rather optimistic however, estimating it might only be

10 to 15 years before such a treatment is available; if he's right, we'll have bugs in the dirt to thank.

"We used to think that microbacteria weren't an important part of the human microbiome," Lowry told

The Denver Post.

"The power of nature continues to amaze and surprise us as scientists and we look forward to learning more."

The findings are reported in

Psychopharmacology.

We'll have to wait 10 years until they have found a way to synthesise a drug!

Strange advice ...