A new study reveals how imagining a scenario that takes place in an emotionally neutral place can change our attitude to that place in reality.

To puzzle out how we learn from imagined events, researchers from Harvard University and the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive Brain Sciences conducted an experiment, first in the US and then they replicated it in Germany.

Participants were asked to provide a list of people they really liked, people they disliked and a list of places they had neutral feelings towards. Then, while lying in an fMRI scanner, they were asked to imagine meeting someone from their liked-list at one of their neutral places.

All up, 60 people lay in an MRI to do just that, but the data of 12 of them had to be eliminated after two of the volunteers hilariously managed to fall asleep in the process, while the others struggled to be still enough for accurate imaging.

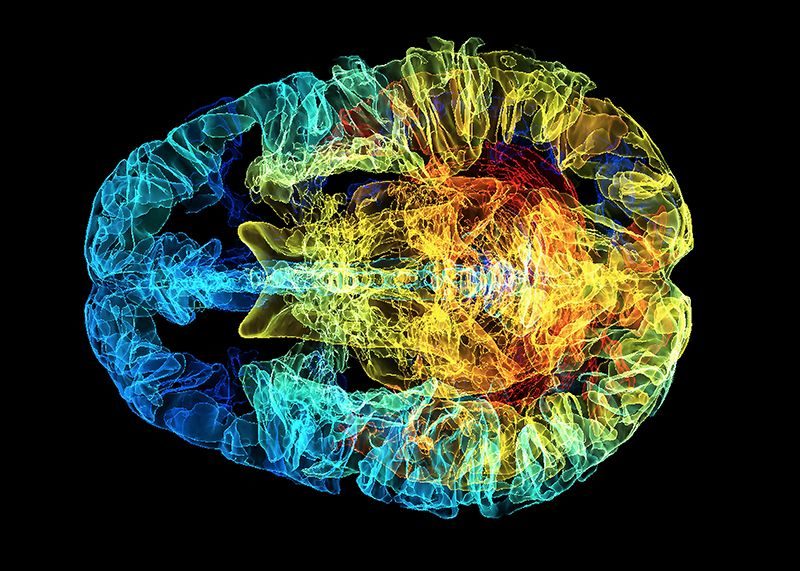

The MRI scans revealed our ability to imagine these scenarios involves a network in our brain that includes the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) - an area that has been linked to processing risk, fear, decision making and evaluation of morality.

"We propose that this region bundles together representations of our environment by binding together information from the entire brain that form an overall picture," said cognitive neuroscientist Roland Benoit.

The researchers explain that while the vmPFC does not code for individual entities such as people exactly, but patterns of coded individual features represent individual people or places within this part of the brain. And they were able to see participants' attitudes towards their neutral places change through changes in activity levels in of these neural patterns.

"When I imagine my daughter in the elevator, both her representation and that of the elevator become active in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. This, in turn, can connect these representations - the positive value of the person can thus transfer to the previously neutral location," Benoit explained.

That the attitudes can transfer in this way confirms those brain parts not only hold the imagination of the place in our mind but also codes our evaluation of the real place too. So, imaginings, much like real happenings, can influence our attitude of the real world.

Evidence that we can alter our attitude towards a place merely with a daydream adds weight to the ideas that changing our thinking patterns can meaningfully change our reactions to the world - an important concept for mental health.

Of course, the power to evoke change through imagination only applies to our perceptions and the influences those can have on our psychology and physiology. It still has no bearing on altering our external physical realities no matter how many self-help books or politicians pretend otherwise.

But given how disruptive perceptions and emotions can be in our lives, understanding more about this phenomenon could prove highly useful.

"In our study, we show how positive imaginings can lead to a more positive evaluation of our environment," Benoit summarised.

"I wonder how this mechanism influences people who tend to dwell on negative thoughts about their future, such as people who suffer from depression. Does such rumination lead to a devaluation of aspects of their life that are actually neutral or even positive?"

It's an interesting question, and one that many of us who battle with negative thoughts are eager to better understand.

The study was published in Nature Communications.

Notice the play on words, of the title of this article, "perception of reality".

To "imagine", is no different from dreaming, a state of physical being, induced by sleep, enters you into a subconscious world.

The human brain works on many platforms.

I will not divulge what I know, but only to say that this article shows its naivety.