Microplastics are particles smaller than five millimetres. About 800,000 to 2.5 million tonnes of these tiny pieces of plastic are estimated to end up in oceans each year, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

However, not much is known about the damage these particles cause to landscapes as they make their way to the sea.

Agricultural lands are likely to be the most plastic-contaminated places outside of landfill and urban spaces, according to research published in the Environmental Science and Technology journal.

The plastics find their way into agricultural soils through recycled wastewater and rubbish.

Between 107,000-730,000 tonnes of microplastic are added to European and North American farmlands each year, according to researchers at the Norwegian Institute of Water Research.

Biosolids in great demand

Comment: Biosludged: Documentary reveals EPA allows spraying of highly toxic sewage sludge on food crops

Food scraps recycled from our mixed waste bins for compost and plastic products used directly by farmers, such as plastic mulch, were also contributing.

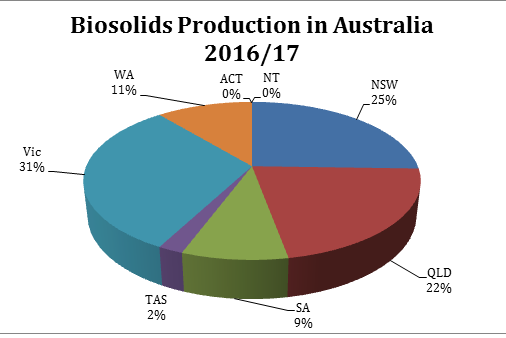

In 2017, Australia produced 327,000 tonnes of dry biosolids in wastewater treatment plants and 75 per cent of it was used in agriculture.

Between 2,800-19,000 tonnes of microplastics are applied to Australian farmland each year through biosolids, according to research in the Science of the Total Environment journal.

"There are farmers in Queensland that are crying out for biosolids and in western New South Wales as well," she said.

"Every time they put a crop into the soil they're pulling out valuable nutrients and carbon, and we can help replace those elements by using biosolids."

Dr Futter said the production of biosolids in wastewater treatment helped reduce the number of microplastics heading directly to the sea.

"What people haven't properly considered is what happens with these biosolids," he said.

"If these are then applied back to the land, you have the potential for contamination and you do have the potential for remobilisation if the soil is eroded or if there's run-off into rivers."

Dr Futter said countless sources, such as clothing fibres, tyre debris in stormwater, and microbeads in cleaning products were contaminating wastewater.

Scientists are not sure what effect microplastics are having on our agricultural ecosystems.

Mark Browne, an ecologist specialising in microplastic pollution at the University of NSW, said a lack of awareness had resulted in limited research funding.

"We get a lot of confusion out there about where this material is accumulating most and what sort of problems it's causing," Dr Browne said.

"This causes us to put all sorts of management plans in place to combat certain products we think are emitting large amounts of microplastics.

"We find out later on, because the scientists have been ignored, that these problems are actually larger elsewhere."

Dr Browne was concerned this hidden build-up could affect soil function and put hazardous chemicals in the food chain.

"We've shown these tiny particles of plastic last for a long period of time, and they can be accumulated by organisms and they can transfer from point of entry into organisms' tissues," he said.

However, Dr Futter said scientists did not have the full picture.

"We can speculate, as certainly plastic can have hazardous substances like endocrine disrupters and carcinogens," he said.Plastic regulations

"These substances can leak out and there can be ecological effects on the soil fauna, which is needed to maintain soil health.

"We don't know very much at all about possible transfer to crops or possible transfer to animals ... so we're very much in the dark."

Australia's regulation of biosolids is strict compared to other countries.

Ms Hopewell said parts of the regulation ensured end use was appropriate.

"You wouldn't put carrots or lettuce on biosolid-amended soil unless it has had a certain withholding period," she said.

Ms Hopewell said regulators and industry were aware of issues with heavy metal contamination and pathogens but not plastic.

"I haven't seen enough research on microplastics in biosolids to date, but it is definitely something we have to be on top of," she said.

The Australian standard allows up to 0.5 per cent of rigid plastic and 0.005 per cent of light plastics in compost, soil conditioners, and mulches.

Dr Browne said that was still quite a lot of contamination and there was not much consideration to what kind of plastics were acceptable.

"We need to be asking clear questions. Even when these plastics are applied to land, how easy is it to remove them again?" he asked.

"These are problems the public needs to be made aware of."

A Department of the Environment and Energy spokesperson said state, territory, and local governments were responsible for the environmental management of waste and resource recovery, including the application of material to farmlands.

"The Australian Government is working with states and territories on a number of initiatives such as the development of a strong, national action plan to implement the 2018 National Waste Policy which contains a number of strategies that will help improve the environmental management of waste and resource recovery," the spokesperson said in a statement.

Ms Hopewell said the partnership would be looking to find funding for future research.

"We don't want to be sending plastics and spreading them out across all the fields," she said.

Comment: The underestimated threat of land-based microplastic pollution