Basing our discussion on Peter Townsend's The Mecca Mystery: Probing the Black Hole at the Heart of Islam and Shiraz Maher's Salafi-Jihadism: The History of an Idea, we take a look at what the historical record really tells us about Muhammed, Mecca, and the principal power players around when Islam began, as well as what modern jihadists truly believe - based on their own theorists and their foundational writings. So if you were ever curious about Islam, join us today on the Truth Perspective for the beginning of a discussion into these complex and controversial topics.

Running Time: 01:44:03

Download: MP3

Here's the transcript of the show:

Corey: Hello everyone and welcome back to the Truth Perspective. My name is Corey Schink and joining me in the studio today are Adam Daniels,

Adam: Hello.

Corey: And Harrison Koehli.

Harrison: Hello.

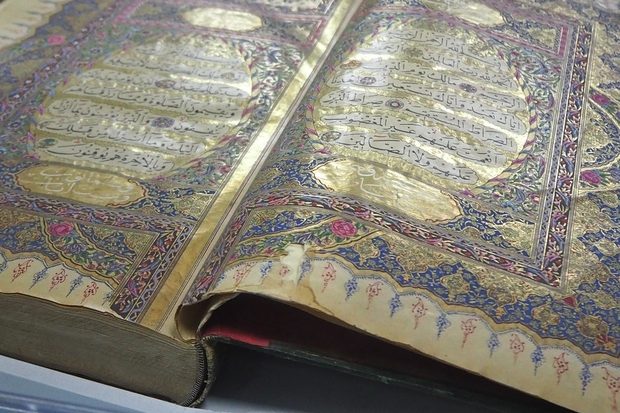

Corey: Today we're going to be discussing the history of Islam. Since the early 19th century western investigators have been attempting an objective and critical history of Islam and the Qur'an. Investigators such as Abraham Geiger, Theodor Nöldeke and Heinrich Speyer, among others, investigated the language of the Qur'an as well as the origins of many of the stories it contained. Two of them made lasting impressions on the field with Nöldeke developing a hypothetical chronological development of the text within the Qur'an and Geiger setting out a framework for understanding the sources of Islamic scripture within Judaism itself.

However, over the 20th century such reductionist approaches towards the subject similar to those methods used to critically analyse Christian origins were tarnished with the label "Orientalists" and "colonialists". Edward Said, author of Orientalism wrote, "To say simply that Orientalism was a rationalization of colonial rule is to ignore the extent to which colonial rule was justified in advance by Orientalism rather than after the fact." These kinds of attitudes obviously hamper progress in the field even today when academics have to publish their plain-spoken work on Islam under pseudonyms for fear of slander, death threats, or if you're Robert Spencer, getting kicked off of Patreon or Twitter, etc.

But they continue to publish so thankfully today we have plenty of material to do through. In recent years we've witnessed a pretty huge political fault line emerge across the western world and in Europe specifically. Islam is a core component of that divide. So it's safe to say many people are curious and justifiably curious about what exactly is going on within their countries and what kind of a background and history Islam really has. So on today's show we decided it's time to take a look at the scholarly material concerning its origins in much the same way as we at SOTT.net have taken a critical look at Christian origins.

We've been reading a number of books, including Peter Townsend's The Mecca Mystery - Probing the Black Hole at the Heart of Islam. Now Peter Townsend is a pseudonym as far as I can gather. You can't get much information on his actual background through the web, but the book is easily the most accessible to the lay person and it's clear by the references he provides, that I've checked, that he's done his homework. He seems to use them faithfully. You can follow through the book and track down every quote or every statistic that he cites and you can judge for yourself whether he is being faithful to the original work.

So that said, it seems to me that it would be good to use the framework that he has set out in order to discuss this field, this subject. Adam, do you have anything that you want to say about that framework, about how he sets out the book?

Adam: Well he starts it off with taking it through with an Idea of History laying out of what it is that we should be doing as far as understanding and critically examining historical texts. So at the very beginning, this is for lay people. It gives you a good understanding of "Okay, here's how you go about sorting everything out into primary and secondary sources and then taking that and dividing it up into archaeological evidence, an oral transmission, a primary source." If it was a history of the Napoleonic wars, this is something that Napoleon himself wrote.' So I thought that was really good as far as giving you the context of 'this is what history is and here's how we critique it and here's how we examine it and then here's what Islam is'.

Corey: Right. I think that's one of the main points he stresses. If you're just a normal person in a western country and you're just curious about the history of Islam, you might pick up a translation of the Qur'an. But if you're going to do that, you're going to find out relatively quickly that the Qur'an is a very de-contextualized text. I think it contains three references to Mecca, the most important city in all of Islam. It might actually just be one or two and it contains only three or four references to Muhammad himself, the prophet, the most important and critical figure in the religion.

Harrison: His actual name?

Corey: Yeah, his actual name. There's only three or four references to it. And there are very, very few references to actual landmarks or anything that you could identify so that if you were going to study the history, if you wanted to know what was going on and where it was going on, you can't use the Qur'an to do that. This has been an issue for Islam for the next hundred years after the Qur'an actually became a concrete text; there was so little to go by that a lot of people had to create sayings, expressions. They had to come up with a biography of Muhammad and his life and it wasn't until the 9th century that an actual comprehensive list, a biography of his sayings - it's referred to as I believe it's pronounced a hadith - which is all the texts that supplement this big gap between the religion and the Qur'an.

Harrison: Before we get into some specifics on this study, I want to provide some context because you mentioned that we have looked at Christianity in this sort of way. So I want to give a little background on how this is done in those fields too because just like we are finding now with Islam, it's actually very hard within the Judaic and Christian traditions and even scholarly fields to do a really objective, dispassionate study of the history of what is alleged to have happened in what we call the bible.

It's not that it doesn't get done but if we just take a couple of example, if we look at the history of the Hebrew bible, the old testament, there's actually been a lot of critical study of the bible, most of it having been done in the last 100 years but really in the past 50 years is when it's really taken off. But even then, if you look at the so-called Copenhagen school, the biblical minimalists like Thomas Thompson and Philip Davies and a bunch of other guys but those are two of them, we've talked about some of their works before and of course Russell Gmirkin who we had on the show a couple of years ago to talk about his book on the old testament's relation to the writings of Plato.

Basically what you find is that you come up against the same kind of issues. With the old testament, here's this book that is widely acknowledged to have been written over a period of hundreds of years. Of course first of all, the first books are alleged to have been written by Moses himself. Very early on in the critical study of the bible, scholars realize that was kind of nonsense because here he is narrating his own death and talking about a bunch of stuff that he couldn't possibly have known, etc. So it's like, "Okay, well maybe that's not true" and slowly the date of composition has gotten closer and closer in time, to the point where, as Russell Gmirkin points out, there's no actual attestation of the existence of these texts until the so-called Hellenistic era, after Alexander. This is hundreds and hundreds, sometimes thousands of years before many people have thought the bible was written.

So if you're going to approach a study like this, critically using a scientific framework and method, then you've got to ask "Here's this book. When is the first time we actually have any kind of written record of people acknowledging the existence of this book?" And then you have to look at the texts and say "Okay, well when's the first manuscript that we have?" Let's say we've got a book that's alleged to have been written 2,000 years ago but the earliest manuscript we have is 300 years old. Well that's 1,700 years where we don't know what happened to this text. Maybe we can find another book that was written by a scholar 800 years ago who is talking about this book and he says, "Oh and here is what I read in this book" and he quotes a sentence from it. And you can look at the manuscript from several hundred years later and say "Oh, there's that sentence too so at least that's some kind of confirmation that at least 700 years ago this book existed and had that sentence in it."

You can kind of say "Well it's pretty probable then that a lot of the other sentences that are in this later manuscript were also there when this guy was writing his thing". You can't be certain. You've got to leave the possibility open that maybe there are interpolations, that is text that has been inserted since that time and as for the actual historicity or the validity of the events actually related in this book, that a whole other story. Let's say the book that you're reading is an account of King Arthur. Maybe we've got this book of King Arthur and we've got an attestation of it having existed 500 years after the events alleged to have occurred in it and then we've got an actual manuscript from a couple of hundred years after that. What does that say about the existence of King Arthur? Do we accept that as truth just based on the book existing and these things having happened? Well we have to ask that question.

So that's been going on in the studies of the old testament and that work is still considered fringe. A lot of it gets accepted by the mainstream academic community years afterwards so it's more common nowadays for scholars to admit "Oh maybe Moses and Abraham didn't actually exist as historical characters. They're mythological. They're constructs. They're cultural heroes and who knows, maybe there was someone named David or named Moses that went down in memory but chances are the tales written about them didn't actually happen and a lot of this stuff is just myth-making." That's not to denigrate myth-making. Myths are a huge pat of every culture.

So a larger number of scholars than could have previously, can accept things like that, where you get to Russell Gmirkin who really takes it down and says, "Here, the bible was written in 320 BC" and there's no reason to believe there was much of anything before that, maybe a few texts and some traditions that got co-opted into the bible and reworked and put into the framework of this new text but that's really our starting point for looking at the existence of the bible and that should be our frame of reference for looking at what's in the bible." And he of course makes his case and it's a really good one.

It's the same kind of thing with Christianity where you look at the historical reality of the figure of Jesus Christ. You look at the documents. Okay, when were they written? When were the earliest attestations of these books? And so the conclusion that a lot of scholars are coming to now for example - this is something that's widely regarded by pretty much every Christian scholar except maybe a few really, really conservative fundamentalists - the gospels probably weren't written by the people whose names are attached to them and they were written at least 40-100 years after the events that are supposed to have occurred in those gospels, the story of Jesus.

So then you have to go, "Okay, well so what are the conclusions we can draw from that?" When you get down to the evidence, there's really a small number of people who take a look at this really critically because for the most part, the people who study the bible are believers and of course believers are humans just like everyone else so they have their biases and their conclusions that they don't want to come to. So you're not going to get very many Christians, if any, who by critically studying the bible will be open to coming to the conclusion that Jesus never existed because that is such a fundamental core of their being that to question that would cause them to totally disintegrate. Their entire world view would disintegrate.

Now that's not to say that that's necessarily a bad thing or that they can't recover from it because some have and some do. As a slightly off-topic thing here, there's this thing called Jesus mythicism. These are the people who believe that Jesus didn't actually exist as a historical personality but that the original Christians viewed Jesus as this celestial deity, so a god that existed in the heavens but not necessarily as what we would consider a human being. So a lot of Christians are very wary of that idea as if to believe that would somehow shake their faith to the core of its foundations. I can see why they believe that but I don't think it's a really valid fear in the sense that if that hypothesis is true, the early Christians believed it. That was part of their faith. It didn't destroy their faith because that's actually what they believed.

Well if it's actually true, then it's possible to believe it and still be religious or Christian. It's just that it goes against the actual beliefs that have been framed in certain words and certain ways over the generations. "Okay, well that contradicts the last 1,700 years of Christian history and dogma and that's a bad thing", but really when you think about it, "If I allow this to break down my current belief I'd have more in common with the first actual Christians". Just something to consider there. But that's all just to say that Christianity and Judaism have been subjected to the same kind of study and we've been more interested in those. We've devoted more time to that, read more books on it but at the same time it is still a difficult study to engage in and to have accepted widely within the academic community.

Corey: You mentioned the psychological biases and how big a role they play in erecting this wall towards criticism of the religion, the text and everything that's associated with it. With Islam there's another hurdle that you have to cross and the is that hadith tradition that I was discussing earlier because that is a tradition that was an oral tradition that was passed down from Muhammad through all of the ancestors, everybody who met him and knows him and had an opinion and could share what he said or what they heard somebody say. There is this kind of a hint of historical accuracy in there that really functions I think to help people say "Well, maybe there isn't really a lot of information in the Qur'an but we have this information and we can't prove or disprove because it's all oral tradition".

Harrison: Like the Talmud.

Corey: Yeah, like the Talmud, exactly. But you can still investigate that. You can still go back and, like you were saying, you can look into the historical record and see if anybody else was talking about this Muhammad character, if anybody else was visiting Mecca because Mecca didn't exist in a vacuum. You had the Roman Empire, you have the Persian Empire, you have Greeks and everybody who would be trading with them and as it turns out, what Townsend points out is that in these dry conditions it's really easy to preserve information over long periods of time. So we have just copious amounts of detailed records, log lists of trade and the trade routes and who traded with whom, who conquered whom.

Just to go back really quickly to what this oral tradition claims, it says that the ancient city of Mecca was the site of immense spiritual and economic importance but by the time Muhammad was born in the mid-6th century, it was adrift in a sea of paganism and barbarity that enveloped the entire Arabian Peninsula. He was a member of one of the most important tribes and received a call from god to act as the prophet in a cave just outside the city and upon acting upon this call he received a series of revelations up to his death in 632 CE and these then became what we know as the Qur'an. Then after his death people burst out of the Arabian Peninsula in the name of Islam and conquered the Persian and much of the eastern Roman Empire in a fit of rage and anger and glory I guess, in the name of Allah.

Now just that first point. As I was saying, there's a lot of evidence there, there's a lot of material data there that if you were to look at it and see "Oh, the Roman empire was trading with Mecca, they were a big trade partner with Mecca throughout the fourth, fifth, sixth centuries, then you could say, "Okay, so Mecca exists. Now let's find out if anybody is talking about Muhammad?" But the problem is that there is absolutely no evidence that Mecca was ever trading with anybody. The Greeks don't have any evidence of this. Patricia Crone discusses this fact in her book Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam. She discusses this in great detail. She goes through all the records and she says there was no Mecca of great importance in the Hijrahs, out in the middle of the desert. Of course there are desert cities that were booming and bustling through trade routes but at that time Mecca would have just been a desert that nobody would go through to trade to. If you look at it on a map and you imagine going from Persia to other large trading partners, it would have been hundreds of miles off the beaten path. Nobody would have had any good reason to trade with it if it existed as this large spiritual and economic centre.

So that's one of the biggest problems. To counter this a lot of critics will say "Well absence of evidence doesn't prove evidence of absence." That's true. Just because there's evidence of absence doesn't mean it didn't exist. But I think that if you told me there was an elephant in my living room and I went and I looked in my living room and a giant elephant wasn't there, then I could conclude that the absence of that was pretty good evidence of absence.

Harrison: Maybe there's a tiny toy elephant hidden underneath your couch.

Corey: Right.

Harrison: That's not really the same thing, right?

Corey: Yeah. It makes sense if it's something small that you wouldn't expect to find. "There's a needle in the haystack, ah, I couldn't find it if the evidence exists in that haystack." Then you could still make that case. But this is supposed to be a huge city that Abraham visited and that played a huge economic and spiritual role for many Arabs who were allegedly adrift in paganism at the time. But it just doesn't turn out to be the case.

Harrison: I've got a couple of questions. So the Qur'an has Mecca as this set place, this setting for the events in the Qur'an in the early 600s, right? That's when this story is taking place. This would imply that Mecca had existed at that point and for some time previously. So the question I've got is when is the first external reference to Mecca?

Corey: So the first appearance of Mecca on a map wasn't until the 9th century and the first reference to Mecca - I'm not sure if this was outside external to the Arab caliphates - was in the mid-8th century.

Harrison: Okay, so 200-300 years later.

Corey: Yes.

Harrison: Okay. so that would seem to suggest - this is just off the top of my head, making an analogy to the stuff that I've read about the old and new testaments - when you have something similar like that that happens in those books, that would lead some scholars to think that looking at the evidence, that might suggest that Mecca came to exist at this certain time, that's when the books were written and then these events were retrojected back in time 200 or 300 years to create a history of this newly established city. You find that in things of the bible and that's why one of the tests for the historical reality of something in a document, in a text, is an anachronism. So if you find an obvious anachronism in a document then you know it wasn't written at the time it was alleged. It was actually written later because that detail shouldn't have shown up earlier in that document.

I don't have examples off of the top of my head in the Hebrew bible but there are examples like that where they're talking about political realities, towns and cities and regional powers that only existed in the Hellenistic era and they're talking about them as if they existed hundreds or thousands of years before that time. So that would lead someone like Gmirkin to say this text is actually being written from the perspective of a writer who lives in this then-current time and who is writing what you could call fake history. He's mythologizing or historicizing these events and putting them back in antiquity when they didn't actually happen back then, or at the very least, let's just hypothesize that he's going on an oral tradition so he's got this vague story. Well he's using details from his present day situation to construct the narrative using these oral details. The problem with that is that, as with any orally transmitted story, you can't verify how old that story is which is also a problem.

But just on that subject, I distrust most of the theories of oral transmission unless you're looking at something that is orally transmitted, if you're looking at tales from a tribal group that don't have written language and they tell their traditional stories. You can say, "These stories really seem to have been transmitted orally over generations". The one thing you can't say about that is the actual definitive form they took 100, 200 or 300 years ago. Chances are they will be similar because there is a very strong continuity in stories like that. But when you look at new testament studies, for instance, for years there was this idea - and it's still around - that a lot of the things in the gospels, for instance, they say "Oh, this must have been an orally transmitted story that existed from the earliest days of the Christian movement.'

But then a lot of those have actually been disproved because you find that the origin for that story is actually in the gospel of Mark and if you look at the way that whoever Mark was who composed this gospel, created the story, it uses a story from the old testament as the frame for creating this story and all of the major elements of that story with these new characters are culled from the old testament. So it seems more a question of literary transmission, that is looking at it in existing text and writing a new text with the old text as inspiration and there's not only no evidence for oral transmission, there's no need to bring it in because all of the elements can be accounted for by textual transmission, by literary mimesis like I mentioned last week.

So those are just my thoughts on this oral transmission. You have to be sceptical of those claims because they are inherently unprovable.

Corey: Yeah, not only are they unprovable but when it comes to such humongous and important things like what the prophet of your religion thought about marriage, about child marriage, about war, about all these things that became the lawS of the land, it makes perfect sense that anybody could come up with just about anything they wanted, put it in the mouth of the prophet then get their way and get something settled in their favour. That's why it took two-and-a-half centuries before they came up with the "sound list" of things that the prophet said and did because it was recognized early on that this was a problem. I think especially from the western perspective, right off the bat, if you're going to be a serious researcher you can't take oral transmission as really good quality evidence. You can see what they say. I think that's an important thing too, especially when you're studying the psychology of Islam and how they portray the prophet.

But getting back to Mecca and how important and central Mecca is to this story. All of the mosques are supposed to be oriented towards Mecca, towards the great mosque. One really interesting piece of evidence is the actual orientation of the mosques up to a certain point in time. When you look at them, the mosques built in the early 8th century, the late 7th century, all of the mosques that were built up until around the 9th century are oriented towards this place far, far away from Mecca but they're all oriented towards the same spot.

Harrison: So these are the mosques that were built during this time that we were just talking about, before the first mention of Mecca. So this is the first 200-300 years of Islamic history which is alleged to have occurred after all the events of the Qur'an. I just wanted to show that connection, that these are the mosques built in that period of time during which there are no attestations for the existence of Mecca.

Corey: Right. And at this time, after Muhammad is supposed to have died and then everyone is supposed to have flooded the peninsula and everything - we want to get a little bit into that later on - at that time after the caliphate grew, after there was the Umayyad Caliphate, there was still no mention of anything really Islamic. They were still printing crosses on coins and anything that had Muhammad on it seemed like it was more of a title because I believe that Muhammad means something like the faithful one or the chosen one, something similar to Christ in Arabic. But at that time they had a vague monotheism that seemed like it was designed to appease as many people as possible in a kingdom that was probably filled with so many different ideas about Christ, who Christ was. You think about the controversies over whether Christ was a man or whether he was divine or whether he was fully divine and fully man. There's one funny tale about one person walking through the city and they stop at the market and there's a disagreement about Christ's identity and then they stop on the street and somebody else is having an argument over Christ's identity. It's just a really controversial time.

So one of the ways that these early Arabic rulers dealt with that was by having this very vague monotheism. But there was a huge element of the population that was a little bit more rebellious and militant so when these mosques start to get oriented away from what looks like the city of Petra in the north-western area...

Harrison: Jordan.

Corey: Jordan, yeah.

Harrison: From Indiana Jones. That's where it originated, is Indiana Jones. {laughter}

Corey: So it was during the civil war that they started to orient differently. Then as they were getting built, they were oriented towards what we would identify today as Mecca. It happens over the course of two-and-a-half centuries where you can see the progression of this idea occurring, not as a distinct religious identity that came bursting out to conquer the land but as this gradual usurpation I guess, of an ideology that was gradually developing its text, developing ideas and then implementing them in a way that was distinctly anti-Christian, almost in a sense that that way you could take this distinct Arabic identity and solidify it.

Harrison: Again, to make an analogy to the other monotheist religions, that reminds me of early Christianity, which started as a more universalistic religion that formed within Judaism as a way of including both Jews and Gentiles, so non-Jews, kind of like "Let's all get together. Let's ignore all these old boundaries and unify ourselves with this new identity." Then within a couple of hundred years it became "Now we've got our identity and now all you guys aren't Christians". Of course we've seen how that plays out over the centuries.

Corey: Yup.

Harrison: I'm curious because I haven't read Mecca Mystery yet. Does he show any maps with the layout of these mosques?

Corey: Yeah.

Harrison: I'm wondering because I'm thinking, imagine myself 1,200 years ago. What's the degree of accuracy to which you could align a building to a place however many miles away and it could be really far away, depending on where these mosques are built. How many degrees off were these mosques? How many degrees was the change at this time to go to Mecca? Was it 10 degrees or was it 45 or 90 degrees? Do you know?

Corey: No, I do not know although he discusses the fact that these were people who were nomadic and they were having to travel across the desert using just the stars, so they had a very good sense of direction.

Harrison: A pretty good sense of direction.

Corey: But how exact it is, no measurements were provided.

Harrison: That would be interesting to see, to see a map with each of these ancient mosques plotted out and then with a line pointing in the direction that they face and then seeing where those points converge. Of course you're going to get some error right, because not every mosque is going to be perfectly situated. Then you compare that with the mosques afterwards and show what they're aligned towards. That would be a good thing to look at, to see how obvious the change is.

Adam: I found the map. So if you actually look at the map that's in the book you can see that Mecca is on the Saudi Arabian peninsula, I want to say middle on the left side, kind of towards the south side. Then Petra, where these other ones were directed toward, was actually way far north.

Harrison: Well it would depend where the mosque in question is, that's aligned.

Adam: Yeah.

Harrison: But that could be as much as a - where's Petra here? - as much as maybe 30 to 40 degrees, if I'm just looking at one point. So it would be quite substantial depending on where the mosque is. Of course if you've got a mosque right at the coast, like in Aden or something, then it would pretty much be aligned in the same direction because there's a line between Aden, Mecca and Petra-almost.

Adam: If there's one in between Mecca and Petra then it's facing the exact opposite direction.

Harrison: Right. So that's interesting.

Corey: A couple more interesting facts. So the first record of Muhammad's death appears more than a century after his alleged death in 632, so that puts it in the middle of the 8th century, which is right around the same time that we're discussing here with the re-orientation of the mosques and all these other happenings.

Harrison: And where is this reference? Is it in the hadiths or is it an external source? Do you know?

Corey: It's in an external source. It's not Arabic. But there is a mid-630s Christian reference to a living Arab prophet armed with a sword and people cite this as evidence that Muhammad existed. But the first actual biography of him appeared around 750 CE and the first Arabic reference to Muhammad appears in 691 CE, the Dome of the Rock, which as it turns out, coincides with a period of strife in which one caliphate gives way to another and this other caliphate decides that they want to cement an Arabic identity against the Christian identity so they decide to erect the Dome of the Rock and on it I believe are the first actual Qur'anic sayings though they're vastly different from the ones that we have today.

But that's the first time that you get an idea of what the Qur'an is going to look like at this time in a very political move.

Harrison: Is there anything else we wanted to talk about from Townsend's book, The Mecca Mystery? Or do we want to move on? Maybe we can come back to his book at another time or is there anything else that we want to talk about, like his thesis and the evidence he presents? Do you want to go forward a bit in time or is that a good place to move on from?

Corey: We could maybe come back to it later on. Maybe something will spark a thought.

Harrison: Okay. Maybe I can ask this question. Does he give any kind of indication of what was going on at the time when these texts were actually written? The reason I ask that is that obviously these stories are presented in a certain way. Certain things happen, right? And didn't necessarily happen in the 100 or 300 years before when they were alleged to have happened. But they must have presented Muhammad in a certain way for a certain purpose. That's the way all books work, right? When you have a narrative you're writing it for a reason. It's only been really recently that we have written history for the purpose of actually writing history. For hundreds and thousands of years it's been a lot more political than that. There have been elements of historiography. People have professed their desire to write truthful events but even within those works you find totally fantastical events that can't possibly have been historical.

So what was going on around the time, even globally or regionally that was the crucible in which these stories took root?

Corey: That ties in with the whole idea that the Arabs invaded and conquered Rome and the Persians which as it turns out flies in the face of the evidence, which was that Rome was collapsing and that through a series of plagues - and this is increasingly becoming a more mainstream opinion - that the Arabs were just moving in and taking over. So at the time you had this power collapse all across the region and as these Arab communities were moving they were mixing with all of these other Christian groups. There was this hugely critical, I think, dynamic into understanding where the Qur'an and Islam came from; this need to create a concrete identity for these ruling groups in the face of this large collapse, the Persian empire going down, the Roman empire going down and then moving into this chaotic situation. As I discussed early you have the controversies about Christ and Christianity and all these groups were largely Christian and Jewish.

The hypothesis that Townsend puts forward is that a group from I believe Jordan, the Nabataeans - I could be getting this slightly wrong - but that the Nabataeans' ancestors had moved into this area and they were mixing with all of these Christians and they had their own distinct religious identity and their own traditions. They were an empire. They were very powerful at the peak of their culture and that in this cauldron really, they were mixing with all these distinct Christian ideas, identities, and out of that they cemented what came to be a more and more Arabic Islamic identity against the Syriac language. They started to create the Arabic language and from there on then just for basic power moves essentially, Islam was created in order to control these various tribes, tribes that had once been nomadic, used to being at war. Now they were moving into these areas that were colonized, set up and structured by Romans and communities that had been colonized, set up and culturally indoctrinated by Romans and had to find some way to kick that Roman identity out, kick it to the curb because it was so prevalent and so powerful. So what better way to do that than to take that religion, that identity and say "No, you're wrong. We have the final big boss man. He's the real culmination."

One of the earliest Qur'anic publications that was made public was the idea that Christ was never crucified which flew right in the face of the whole Christian mythos, that he never died. I think they said something like that some body double was crucified in his place. But when you look into the texts and the stories, a lot of it sounds like the myths that were coming from some of these other heretical Christian groups. You get stories about Christ as a child and all the different things that he would do as a child. Harrison, maybe you know a little bit more about the smaller cults that these ideas were coming from.

Harrison: I want to come back to this at a later date when we come back to this topic because I'm thinking of this book in particular. I think it's called Jewish Christianity and I think the author's name was Shepps. I can't remember for sure. I want to take a look at this book and come back to this at a later date because what he hypothesized, from what we know about early Christianity it looks like the more Jewish group and the more gentile group. So Paul represented the more gentile group. He was the apostle to the gentiles. He was out to convert Greeks and everyone else living in the Roman empire that wasn't already part of the Jewish community at the time.

But then there were the Christians that were led by James and Peter. It seems like what they wanted to do was maybe accept gentiles but it was more limited to Judaism. So they would accept converts but you were basically converting to a form of Judaism. Paul would have said the same thing but the actual cultural markers of Judaism like circumcision and obeying all of the Torah rules for Jews. It looks like after the Roman Jewish war in the late '60, early '70s of the first century, that the remnants of this Jewish Christian group fled into the desert and continued on with their traditions. This guy Schepps actually hypothesizes that these were the kind of groups that carried on for the next several hundred years potentially and from within those groups we get the Islamic tradition coming out of there.

For this group in particular I don't think there's a lot of solid historical evidence for what they actually believed. That's why I want to go back and look at this because I'm not really familiar with how their beliefs differed. But definitely within the known Christian history of controversies within Christianity, there were the beliefs like you mentioned; the controversy between those that believed that Jesus was really a human who was crucified and those who believed that he wasn't and those who believed that there was just a ghostly form that came down and appeared to have been crucified and then some that he actually died on the cross and some that he didn't die on the cross, etc., just every possible permutation of those factors was characterized in some kind of Christian group. That would be interesting to find out too.

That's one of the things I want to look at over the coming months, the environment in which Islam got the form that it's been codified as, that has come down to us now today in the texts because when you look at the beliefs of Muslims today, of course just like with Judaism and Christianity, all the Muslims today believe all this stuff actually happened. So whether they did or didn't, they are accepted by a large number of people as historical reality and not just historical reality but as moral and religious imperatives. So these are the things we must believe and must do in order to be true Muslims, true humans, true whatever, just like any other religion.

That's an important thing to look at also. It's kind of looking at it from two directions. One would be 'what really happened' and one is 'what do people believe today'. Knowing what really happened can be used to undermine the beliefs of people today but at the same time you have to take into account the beliefs of people today in order to understand what people do and why they do it. Just to give an example from the old testament, if you look at Israelis and some of the common justifications for the state of Israel, to put it crudely, 'god gave us this land because the bible said so'. As much as the minimalists or the critical biblical historians can say 'That's not actually true, look at this history. Your history isn't exactly what you think it is', that's never going to sway the beliefs of the Jews that believe that.

So you have to take into account those beliefs. You basically have to treat them on their own terms. But then at the same time, you don't need to show that the history wasn't wrong or that the history didn't happen in the way they think it happened in order to criticize that belief because even if you encounter a Jew or a Christian who believes that the reason that Israel should exist and the justification for any acts that are committed by Israel in the pursuit of maintaining the state of Israel, you don't have to bring that up because the premise is basically 'This is what it says in the bible, therefore I am justified in taking this land and doing what I want with it'.

But the conclusion doesn't follow from the premise or the premises if we expand the syllogism. Just because it happened in the bible, let's just say it did. Let's just say the bible is actually accurate. That still doesn't justify things. There are different ways of looking at the situation and different things to look at. So we have to separate out the area of study that we're looking at and the purpose of that study. Why are we necessarily looking into the history of all these religions? Well that can be to get to the truth. Another question is looking at the beliefs and actions of identifiable groups today and then saying okay, what's our purpose there. It could be to criticize either the morality or the validity of certain political moves and certain cultural practices or whatever so we can establish a chain of causation and other things too. I'm just saying there's different things to keep in mind whenever we're looking at anything like this.

Corey: I agree wholeheartedly because I think what you're saying is there's a difference between ethics and history. You can make a distinction there when you're analysing or trying to criticize a religious system. But then also when you go through history you can see where the corruption comes in. In Political Ponerology, Lobaczewski talks about how it depends on where corruption comes in, on whether a tradition is salvageable or not.

Harrison: We talked about that when we covered the chapter on religion and pathocracy.

Corey: Yeah. So going back through history, if you can see where the corruption sets in, then that can tell you what in your ideology or religion or this belief system, is worth saving and what isn't. One of the most interesting things I think that comes out of reading The Mecca Mystery is that the same types of people who are coming up with these grand biblical narratives were hard at work doing the exact same thing in Islam, in the same places, in the same cities even. He discusses Babylon specifically. I just thought that was interesting.

Harrison: Expand on that? I didn't understand what you just said.

Corey: I don't actually know if I can expand on that. I can't even remember. {laughter}

Harrison: Okay. I wanted to use that meandering point that I made to transition to a book that I just started reading by Shiraz Maher. I'm not sure how to pronounce his last name. It's called Salafi Jihadism, the History of an Idea. The book itself is an intellectual history of the so-called Salafi Jihadist movement. I'll get into how he defines that but basically it's a modern form of Islam. That's why I was saying we have these different things to approach and different ways to approach them. So you can approach the original texts and then you can approach the way that they are believed and transmogrified today.

There's another book that I started reading. I haven't gotten very far in it. It's The History of Jihad from Muhammad to ISIS by Robert Spencer and the point he makes early on in the book, right in the first paragraph I believe, is that he himself has written a book called Did Muhammad Exist? or something like that, questioning the historical reality of the figure of Muhammad using some of the similar methods I think, that Townsend used. So I'm going to be talking about all these passages in the Qur'an. Keep in mind that while we don't necessarily need to agree about the historical reality, we have to acknowledge that there are millions and billions of people that actually believe that this is what happened so that actually forms their world view. So keep that in mind.

This book, Salafi Jihadism is an analysis of that because Maher goes on to first describe what Salafism is. That's a term that gets thrown around a lot and you say "Oh those Salafists" usually in reference to jihadist militant groups. But what Salafism is, is the belief that in order to practice true Islam what the Ummah, the Islamic community needs to do, is to go back to the first three generations of Islam. So these would be the prophet's direct descendants in those first three generations, like 90-100 years. They say "We the Islamic community need to go back to those original practices" which is kind of an internal confirmation of the belief from a lot of anti-Islam people who say "Oh, they just want to take us back to the Middle Ages". Well it's like well that's actually true. There's a large group of Muslims that actually want that and they think that's the proper way, the true Islam, to go back to the way it was practiced originally.

He gives some examples because as with any religion you'll find variations and controversies and disputes within and between different Islamic groups. So Salafism itself - just to give some overview - its roots are grounded in Sunni Islam. He says "Their roots are grounded in the experience of Sunni Islam over the last century and beyond." He says "The real purpose of this book is to examine and explain the evolution of Salafi Jihadi soteriology which is their religious 'saviour' philosophy", so how do you get saved. That's kind of like the purpose of religion. How do you achieve whatever it is in that religion that you're supposed to achieve? Usually it's thought of as where you go when you die; how to lead a life that you will be rewarded for by god.

So just continuing that train of thought he says, "This is a broad and varied ecosystem of dense Islamic jurisprudence. It has licensed the actions of militant movements across the world. Islamic State is just the latest and most successful group that it has spawned." He's written this book on Salafi jihadism and he actually distinguishes jihadism. Salafi jihadism is a subset of Salafism and of course Salafism is a subset of Sunni Islam and Sunni Islam is a subset of all Islam, the main divide being Sunni and Shia. So he defines Salafi jihadism as the ones that are in total rejection of the current status quo, the current world order and the current governments and nation state systems of the current Islamic world. He gives three different categories for Salafi political preference. This is how he places groups. It's by their method for change and he gives the three possible methods for change-violence, activism and quietism. So the jihadists would be in the realm of violence.

But he says that the activists - these would be people that actively protest against existing governments for instance - can get violent. He gives the example of Ahrar al-Sham in Syria. This is one of the militant groups in Syria. They engage in violence but their political manifesto is limited to Syria. They just want an Islamic state in Syria and they're willing to use violence to get it whereas the Salafi jihadists want to tear everything down. So really they are revolutionary groups. We've got the violent groups, the activist groups but there's a third group which he calls the quietists. He gives the example of the Saudi awakening movement.

"By contrast, the Saudi awakening movement produced a cadre of scholars who operated as activist challengers" - so they're actually an activist group - "by publicly airing their disagreements with the Saudi government and calling on it to reform." So this would be a reform in the direction of a more pure Salafi Islam which is kind of ironic -or maybe not - because Wahhabism, which is the state religion in Saudi Arabia, is a type of Salafism. I should have added that earlier, when we look at that. Wahhabism is one of the main groups within Salafism. "This Saudi awakening group are more directly engaged with the political process lobbying and campaigning for organic change in accordance with Islamic precepts. Moreover, their belief in maintaining social order and unity leads them to reject radical and revolutionary upheaval."

This is totally contrary to the Salafi jihadists who are radical revolutionaries. He gives the five traits for what he sees as the essential features of Salafist jihadism because he goes through some of them. A lot of people have tried to define it over the years. This is a relatively recent book, published in 2016 and I'm pretty sure it's the first book to actually look at the ideology of Salafi jihadism. He points out a lot of people are focused on the military tactics of groups like this but he actually looks at all of the writings by the theorists and the ideologues, the people actually writing the justifications and writing the manifestos and writing the long and laboured theological justifications for everything. If you've read any communist writings you get the flavour for that kind of thing. It's written by ideologues. It has the flavour of it.

So he points out that there are some beliefs that the Salafi jihadists have that naturally are the same beliefs that most other Muslims have or most other Sunnis have. But the five that distinguish Salafi jihadism is their focus on and the particular ways in which they characterize these five things. He goes through each of these five in the book; Tawhid, Hakha-Mia, Al-Wala' Wal-Bara, Jihad and Takfir. I'll go to the glossary so I can read his definitions.

Tawhid is the unitary oneness of god, the core component of Islam and the single most important factor for Salafism. They use that as a political rallying call that the purpose of life, religion and Islam is the unitary oneness of god, to accept that and to put it into practice. Basically that is the justification for taking over land and getting other people to convert because that's the religious imperative. You do that for god because that's the way the universe should be structured. If humans are living right with the universe they will be Muslims, essentially. And of course you can see that in a lot of different religions. And of course with jihad they've got specific justifications for war and methods for war, what is and isn't allowed.

Takfir is the excommunication of other Muslims, so banishing them from the faith. So it's their methods and justifications for who is and who isn't a Muslim. The other two I haven't gotten into yet so I wouldn't be able to summarize them at all. But asically they're for two purposes - the protection of the faith and the promotion of the faith. The protection comes through Al-Wala' Wal-Bara and Takfir, so defining the boundaries. And also jihad. Its promotion is linked to Tawhid and Hakha-Mia. The book is structured on each of those five things and showing how these guys actually talk about those five things, how they relate them to the Hadiths and the Qur'an and thereby justify all of their actions.

Corey: I just wanted to interject for a second because one of the top themes in the Hadiths is the portrayal of Muhammad as an intense warrior. The amount of toxic masculinity - if you want to call it that - that's in the Hadith would blow your mind. He engaged in war with every single neighbouring tribe and city that he came into contact with. I've got a list of things that he did in this long oral tradition. He ordered raids on caravans in order to steal their contents and then sell people for ransom. He allowed his followers to rape captive women. He consistently taught that warfare for the sake of Allah is the highest duty that a Muslim can perform. He taught that those who abandoned Islam should be executed. He ordered the assassination of several people who were critical of him. He was present and did nothing to stop an act of genocide when his followers slaughtered disarmed male members of a Jewish tribe after that tribe refused to embrace Islam and he married and consummated that union with a woman on the same day that her husband, father, brother and most of her family were slaughtered by his followers.

So this is the portrayal of the highest form of character that you could aspire to if you grew up in this religion. All those traits, it's really intense, it hits you right in the face when you read them one-by-one. I didn't grow up in that tradition. I'm not sure how popular those kinds of stories are, but as a male, this is the top alpha dog that you would look up to in terms of forming your traits. So it makes sense I think that these characteristics, these traits would be so visible.

Harrison: One of the points he makes is that oftentimes when groups like ISIS are portrayed in the media, they're portrayed as just a bunch of blood-thirsty psychopaths or murderers, mindless criminals. But actually, as he points out, everything that they do is actually justified and reasoned through based on a text. They have examples for everything. That's not to say there isn't hypocrisy even among ISIS members, but all their main tactics and strategies and pretty much everything they do does have a justification, a really well-thought-through and rational justification. Of course if the premises are wrong you're going to lead to some immoral conclusions and practices but there is that procedure of Islamic jurisprudence.

Just giving the example of jihad, there is a long history of theorizing on jihad and of course that does mean warfare and the vast majority of Muslims agree that it means warfare; the idea that there is this greater jihad which is the struggle within one's self. It actually is a valid idea but it's actually a late idea so a lot of Muslims reject that idea and say "Okay, you can think that but jihad actually is warfare". So there are justifications for offensive and defensive warfare, naturally just like in any society. But especially with the militant Salafis, warfare gets elevated to a moral imperative. I'll just read a paragraph from Shiraz Maher's book. He writes,

"At its core the contemporary Salafi jihadi movement regards physical struggle in the cause of god as the pinnacle of Islam, its zenith and apex. It is the vehicle by which the religion is both defended and raised. This chapter explores the importance attached by Salafi jihadist theorists to the idea particularly with regards to the virtues of combat and its link to the concept of worship itself. Viewed in this way jihad in the path of god is ibadah, an act of worship akin to ritualistic acts such as prayer, pilgrimage or fasting. This chapter also explores mainstream Salafi jihadi positions on defensive jihad before explaining how the global jihad movement appropriated these opinion to license its war against the west as a legitimate and necessary defensive measure."

So he actually goes through all of the mental gymnastics in order to get to the point where Salafi jihadists today can justify just killing anyone. Ironically but not unsurprisingly, that has led to fractures within the Salafist community itself.

He gives examples of some of the early Salafist jihadist theorists. These were the guys writing the tracts, writing the monographs, the treatises who give this very steady defence of offensive jihad who have turned on the movement because of what they see in the actual practice of these Salafi jihadists. They're saying "You guys can't do that" because there's this whole idea of the killing of women and children and basically innocent civilians. It has gotten to the point through this theorizing that that is allowed for these groups and they use it as justification, the Islamic the law of equal retaliation. This is called qisas.

So it's based on certain texts from the Qur'an justifying these things but then these guys come along and say "You guys are really expanding the definitions here because yeah, there are these verses that say, for instance 'whatever wrong is done to you, you mete that out to the person that wronged you'," something like that. I'm paraphrasing. Kind of like 'an eye for an eye', the same principle. The very next verse says "Oh, but you should be moderate because Allah judges harshly" but they leave out the second part and just focus on the first part.

I think it's kind of ironic because you'll get a lot of westerners who are critical of the anti-Islam stance who'll say "You're just misinterpreting the Qur'an because the Qur'an actually says this". Well yeah, and that's what Muslims will say too and even some Salafist groups. But you do have the groups that don't care. They will theorize whatever they want to and will justify it however they want to and that's essentially what has gone on with this example of jihad.

With that in mind I want to read a couple of paragraphs from Ponerology because I think there's some relevant things here. So first I'm going to read a paragraph from the section on spellbinders. Lobaczewski writes,

"In a healthy society the activities of spellbinders meet with criticism effective enough to stifle them quickly. However when they are preceded by conditions operating destructively upon common sense and social order such as social injustice, cultural backwardness or intellectually limited rulers sometimes manifesting pathological traits, spellbinders' activities have led entire societies into large-scale tragedy."

The next section on ponerogenic unions like gangs or psychopathic revolutionary groups he writes,

"The earlier phase of a ponerogenic union's activities is usually dominated by a characteropathic particularly paranoid individual..."

So people with personality disorders.

"...who play an inspirational or spellbinding role in the ponerization process. Recall here the power of the paranoid characteropath lies in the fact that they easily enslave less critical minds. For example, people with other kinds of psychological deficiencies or who have been victims of individuals with character disorders and in particular a large segment of young people. At this point in time the union still exhibits certain romantic features and is not yet characterized by excessively brutal behaviour. Soon however, the more normal members are pushed into fringe functions and are excluded from organizational secrets. Some of them thereupon leave such a union."

Then one last little bit on ideology,

"The ideology of unions affected by such degeneration has certain constant factors regardless of their quality, quantity or scope of action, namely the motivations of a wronged group, radical righting of the wrong and the higher values of the individuals who have joined the organization. These motivations facilitate sublimation of the feeling of being wronged and different caused by one's own psychological failings and appear to liberate the individual from the need to abide by uncomfortable moral principles. In the world full of real injustice and human humiliation, making it conducive to the formation of an ideology containing the above elements, a union of its converts may easily succumb to degradation. When this happens, those people with a tendency to accept the better version of the ideology will tend to justify such ideological duality. The ideology of the proletariat (communism) which aimed at revolutionary restructuring of the world was already contaminated by a schizoid deficit in the understanding of and trust for human nature. Small wonder then that it easily succumbed to a process of typical degeneration in order to nourish and disguise a macrosocial phenomenon whose basic essence is completely different."

In these three little excerpts I think we've got a perfect description of the Salafi jihadist movement. What's the environment in which these jihadist and Salafist movements have arisen? I can't speak for 150 or 200 years ago but in the last 100 years there have been great geopolitical changes and foreign meddling and in the last 20 years warfare and very rightly, and not just the Muslim community but the multi-confessional community, nations like Iraq and Afghanistan, Syria and Libya have been under attack in various ways including actual warfare and bombs and millions of deaths.

This is like what Lobaczewski says, that these ideologies arise in times of real grievances, real bad things that happen. Where's that bit that I just quoted? "Real injustice and human humiliation" and that these ideologies arise and what are their goals? Well their goals are always the same and their goals always make sense. They're the motivation of a wronged group. What is their goal? To radically make right the wrong that was done to them and then to elevate the individuals who join the organization to the level of the highest valued individuals.

So essentially what you have is really a tragic scenario, right? And this happens all the time. When you have a group that does suffer a wrong, what are you naturally going to get? You're going to get primarily a lot of young men who see what's being done to them and being young men, like all young men across the world and people being self-centred, they're more willing to see the fault in another person than they are within themselves. So naturally that will combine with the actual wrong done to them to totally demonize the enemy and of course it is an enemy.

So you will get a movement that will form. It could be a national resistance movement like sprung up in Iraq, who are fighting for their freedom, but there's this ideology. So you have these real reasons for fighting, these real reasons for joining a militia, to protect your family, to protect your village, your town, your city, your country but this is how revolutionary ideologies take hold. It's the same thing in Ukraine. Like I said last week, I'm reading this book, Ukraine Over the Edge by Gordon Hahn and he talks about the rise of Right Sector and all the different neo-fascist groups that went into the creation of Right Sector. Right Sector was actually created on the Maidan. That's when it started.

Then he goes into all of their actual writings and what they believe. If you look, western Ukrainians haven't had it easy for a long time and currently today. Even in Ukraine, western Ukrainians are the poorest. They suffer from the most poverty and they've gone back and forth between nations. Borders have changed around them and they have never really had a lot of political representation. Imagine yourself a young man in that situation. It's no surprise that he might join a group like the Right Sector. But the problem is that these are the types of groups that ponerogenesis happens in. These are the types of groups that get ponerized.

That's why I say it's a tragedy. You look at the people in Czarist Russia, you look at the revolution that went on. Not everyone engaging in the revolution wanted what they ended up getting. It's not like they would have predicted saying "We want a revolution and we want Stalin and we want him to do this". No, that happened but that's not what they wanted. The revolution took its course and the tragic thing is that revolutions take their course and they tend to take them in the same direction. Violent revolutions that make things worse are far more common than non-violent revolutions that actually get the changes that the revolutionaries want.

Corey: Right. And one of the big problems, as Lobaczewski points out, is this schizoidal ideology that functions as the system of coordinates for all of these people and how they act. Albert Einstein described the movement of heavenly bodies as contingent on a system of coordinates that empirical data were of use only insofar as they could be related to a field of perception already plotted. So when you have these conditions set up and then you throw this schizoidal ideology into the mix, this is the system that you have to go by. I think that's what really lends the shield for these kinds of characteropathic individuals who are doing things that are so unnatural that if you had a more realistic system of coordinates, that you would be able to see, 'no, this isn't what we should do. This doesn't make sense. We should think this through. This should be more logical. We can't just assume we know that the proletariat of the masses is going to solve all the world's problems.'

When you have that deranged system in place, I think that's really a critical factor in why things get so bad. But as you point out, revolutions run their course. Revolutionaries run their course really.

Harrison: The Salafi jihadist movement really got to the point, like Lobaczewski mentioned, where the old members are no longer welcome. A person outside the belief system would look at a Salafist and say "Well, they're pretty radical". But some of them have left or been ex-communicated from the movement because they aren't radical enough. Like you said, that's just the natural progression of things.

One of the really ironic things that I found in this book just in the first 40 or 50 pages is that he points out that the actual Salafist jihadist movement didn't really exist until the second Iraq war, 2003 to the present. Before that there were Salafist groups but they didn't really have a core ideology. There were a bunch of conflicting opinions and it was really only in the Algerian war in the early '90s that these ideas started taking root. So it's taken almost 30 years but nowadays there is this identifiable ideology and it has been born in actual warfare, partially out of the necessity of warfare and then the practical working out of beliefs and actions that have already been manifested in warfare to the point where now there is a movement.

So the irony is that in the '90s there was a small minority of concerned individuals who actually saw what these people were writing and were genuinely and rightfully concerned about it. I mentioned Gordon Hahn who wrote this book on Ukraine. He was actually one of the guys in the late '90s who was one of the only westerners who was looking at what was going on in Chechnya and saying "This is a bad situation. Russia is facing an Islamic threat within the country." From the western mainstream perspective Russia was just facing an Islamic separatist movement and Islam didn't really have anything to do with it. It was like Chechnya and Dagestan. They were the oppressed minorities in these regions and they wanted their independence from Russia.

Of course, long history again of historical grievances, real wrongs done through the course the interaction with the Russian empire and the Soviet Union and even in those first years, those groups might have been considered if not Salafists, then very similar to the activist movement that Maher includes in his categories. They weren't bent on global jihad. They just wanted independence and they fought a war for independence and there wasn't actually any kind of infection by the jihadist movement in those early years. It was only in the later years that ex-al-Qaeda or people who fought in Afghanistan and Bosnia started going into Chechnya and gaining converts and really jihadizing the movement there. This is what Gordon Hahn was warning about saying "This is actually really bad". And of course no one was listening to him.

So it got to the point where these groups eventually amalgamated and solidified into the Caucasus Emirate who then pledged allegiance to ISIS and now most of them are in Syria fighting or dead. But there's still some of them in Chechnya and Dagestan. You can watch videos of the FSB rooting them out of their holes in the forest where they hang out and terrorize the villages during the night. It is a problem still and that's one of the main reasons that Russia went to Syria in the first place, the relatively huge number of Russian citizens and central Asians who went to Russia and would have come back.

Corey: This Salafist mercenary jihadi type individual, you said that this ideology that they have took many years for it to develop its own distinct identity.

Harrison: Mm-hm.

Corey: How recognizably Islamic is it? Are you supposed to read the Qur'an before you go, murder everyone? Because you hear stories coming out of the Middle East, especially in Syria with cities being liberated, you get the idea of what you were discussing earlier about this ideology wanting to turn back time to the medieval age type of living conditions in terms of women having to wear their burka and you get your hand cut off if you steal, those kinds of punishments. Is this a Sharia law? I'm not exactly sure how I'm trying to say there.

Harrison: Is it a religious movement.

Corey: Is it fundamentally a religious movement?

Harrison: Well that really depends on what angle you're looking at it from. If you ask these guys they'll say yeah. But there's all kinds of things to consider. When you look at a lot of the new converts to ISIS, a lot of them are newly converted to Islam and they're young. So these are the susceptible individuals that Lobaczewski talks about, especially if you're a young guy. One of the points that Maher makes - let me see if I can find it - he talks about the actual ideology. "A brief note on ideology is also needed given that it informs the cornerstone of what is being examined here. In its most basic construction, ideology is distinct from the political way of thinking by attempting to bring together a series of speculative abstractions into a coherent doctrine in the pursuit of utopia or at the very least, a better way of living."

He says elsewhere, "To this end Salafi jihadism exhibits a tendency towards brutal nihilism with its desire to forcibly replace everything other than itself. Its adherents also recoil at the permissive egalitarianism of contemporary societies, seeking a return to the more assured, albeit absolutist times. Satiating ideologies consequently provide their adherents with a form of common cause, a unifying mission and a sense of purpose for bringing society together." That's what it comes down to. There is this very definite ideology and it provides a sense of purpose for these primarily young males. On the one hand you get a guy like Jordan Peterson who provides meaning and purpose to people's lives and on the other hand you can have groups like ISIS who do the same thing but it's a different type of purpose and a different type of meaning but it's the same principle operating there.

So what I was going to say about these new converts to Islam who go over to join ISIS, from the insider reports and the documents that have been released from liberated areas and first-hand accounts, what happens when they go to join up, they fill out a questionnaire and are asked the question "What's your proficiency and knowledge about Islam" and a lot of them will say "Not very much at all". So this can be seen as evidence that these aren't real Muslims, but really, what do I know? I'm not an expert. When they join they actually are indoctrinated. There are rules. There are imams that are leading prayer and there is a religious, ritualistic aspect to everything that they do.

Now of course, keeping in mind what Lobaczewski writes about these ideologies, in a sense that is the original surface ideology. As pathological as it is, that's still just the surface ideology. Behind that is the actual psychological psychopathology that's underneath the surface to the point where you can get hypocrisy even within that pathological system where some of these guys might actually violate their own precepts.

Corey: But that's just the rule for centuries.

Harrison: Right.

Corey: There's a certain set of standards for the elite, that they set the standards for everyone else, especially in Saudi Arabia. The elite in Saudi Arabia, you hear about them flying and doing all sorts of crazy things in their billion dollar palaces while the man on the street, if he's singing, he's going to get flogged or a woman cheats, she gets her head cut off. But I'm sure there's no such thing going on for them.

Harrison: Right. I didn't read it but in one of those sections that I quoted from Ponerology, Lobaczewski writes that the original ideology is used as the measure by which younger, more naïve members are held to account. So even though it's just a mask, it's still used as the rules for membership, essentially, the rules for initiation.

Corey: The game that we're going to play.

Harrison: Right.

Corey: We all need a game that we know how to play and this is going to be the game. Part of the game is knowing that the elite don't play the game.

Harrison. Right.

Corey: You just know that's what's going on but who are you to say anything?

Harrison: Right. That's why I said it depends on what angle you're looking at it from because for the fighters themselves it is very religious. This is their purpose in life. As Maher shows in the beginning of the book, he makes reference to a book I read a couple of years ago called The ISIS Apocalypse by William McCants that they really are an apocalyptic movement. So this guy points out the kind of paradox in their beliefs because on the one hand they have this constructive ideology about state building - or they did before they got slaughtered - but on the other hand, they're totally destructive because they're actually planning for the end of the world.

You can see this in a lot of the suicide bombers in Syria. If you've ever watched some of the propaganda videos from ISIS, you see these guys, they show them and they go to their deaths willingly, believing that they're fighting for a good cause and that they will be rewarded for engaging in warfare. That was kind of implied in some of the quotes I read. I didn't read the ones that explicitly say it, but when he's saying that jihad is essentially a religious ritual and apex of Islam for these guys, that's true, that level of indoctrination and self-purpose, that pathological purpose that will allow someone to just go into battle knowing that they're going to die. Even then, that's universal in warfare where you're in warfare, you're fighting for a good cause and you're going to sacrifice yourself for the greater good.

In this case, from the outside you can say no one accepts that that's the greater good and it looks weird. It looks like there's something wrong going on here.

Corey: Right. But when you tap into the kind of nihilism that this movement is drawing on within its members and the nihilistic environment which they live in, surrounded by warfare and poverty and all this and then you factor in that extra little pathological element, that chaotic element that you see in figures on the macroscale like Hitler, if you read about him you get the impression that - I think Jordan Peterson discussed this and several authors have discussed the fact that - maybe he wanted to die while Europe was in flames. Maybe that was a deep-seated desire of his because of how sick and disgusting he was.

This is part of the psyche I think that's active in these individuals, why they do the crazy things that they do. They can go into battle believing that they will be rewarded eternally and that nothing that they do is unethical, that they should feel guilty about, that it's actually something to be revelled in, the fact that you have conquered human morality. You have conquered society. You've conquered this enemy of reality that's been keeping you down. You just look it right in the face and you spit in its face and then believe that you're going to heaven afterwards. Of course, the ethical claim of that is highly debatable, that you're going to heaven after that. That's about as crazy a claim I think as you can make but that's a part of the whole package, is the craziness. Actually I find it really interesting that this Islamic movement finds so much ideological justification within Islam.

From what I've read, just in The Mecca Mystery and I'm also reading another book on the linguistics behind the Qur'an, you get the idea that a lot of the Qur'an is basically the same stories from the bible, similar stories from the new testament, stories that were passed around about Jesus that never made it into the canon of the west. But then after that you get that large commentary, like I discussed earlier, the Hadiths. Who knows who these people were? They could introject their opinion on who the prophet should be. If the prophet is only mentioned by name three or four times, I don't know how his character is described in the Qur'an, but I'm assuming that it's not obviously set out because these people felt like they had to spend 100 or 200 years describing "This is what he did. This is what he said. No, actually he said this. No actually he did this. He likes to murder people. No he's pro-peace."

Adam: Yeah, all you have to do is just throw in a couple of people in front of you and say that you got it directly from the guy and then you can say pretty much whatever you want.

Corey: Right. That seems to me what a huge chunk of that corrupting pathology got swept in there because it just strikes me as odd. I haven't read the Qur'an but from what I've read about it, it sounds like the same stories, the same kinds of principles and then a lot of it that can't be understood because some people think that it was written in Syrian and not Arabic. There's some translation issues that nobody can understand what the heck's going on in the book. But it's just such a confusing mass to have at the centre of your culture.

Harrison: I have one point that I want to finish up with before we end the show for today. I was talking about the irony of the Salafi jihadist movement really gaining steam in the second Iraq war. For these guys that saw the problems in Salafism in the 1990s, of course there was the problem, and the solution was the war on terror, presumably. Of course there were other motives for that too but the war on terror just made things worse and actually gave birth to a movement that didn't really even exist beforehand. There's no real comparison between the Mujahedeen of the 1980s to ISIS today. The ideology has solidified and it has gotten to the point where, like Lobaczewski describes, this is an ideology. The problem with ideologies, especially pathocratic ideologies, is that they're decentralized and that is a feature of ISIS and other types of groups.

Lobaczewski says the leader doesn't matter. As much significance is given to any leader of any movement, whether it's Osama bin Laden or Stalin or Hitler or Al-Baghdadi, the leaders actually don't matter very much because the ideology itself acts as this kind of broadcasting system as Lobaczewski describes, that is then picked up on by susceptible individuals, by like-minded individuals anywhere. The west has, in a sense, created ISIS in more than one way, but are not the only ones who have created it because you can't take the blame away from the people who actually created it, actually wrote the books and actually trained the fighters - well the CIA did some of that.

Corey: Joined it.