The community has turned against the asylum seekers who have been setting sail toward Italy in search of a better life. The new mayor is talking about barring the way to fresh arrivals. Pani's old neighbors are campaigning against a proposed migrant reception center in their midst. And a priest who dared to shelter an undocumented Ghanaian man was slapped with a fine for failing to tip off authorities to his presence.

Many in this city of 90,000 are in good company in Italy, where moods have soured as the country faces a seemingly limitless flow of people taking boats across the sea from Africa. Leaders are struggling to integrate the more than 500,000 migrants who have landed since 2014, even as new asylum seekers arrive almost daily.

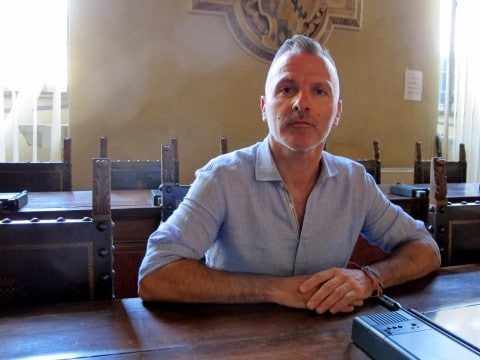

"I've been shocked about the reaction of the town. I knew it wasn't exactly the center of the world," said Pani, a 39-year-old film production manager. "But here we really have had a fear of differences."

Pistoia's former leaders - allies of the center-left party that rules Italy - thought they had the situation under control when the first migrants began showing up three years ago. But more people kept coming, and eventually some of them became fixtures in the city's 13th-century piazzas and its parks.

"In a community like this one, we noticed when we started seeing issues more typical of big cities," said Iacopo Vespignani, 43, a newly elected local councilor who always voted for left-wing politicians until he ran this year on a right-wing ticket.

"I'm not talking about anything illegal. But there are people standing in front of every cafe and bar, in front of the hospital, standing in parking lots. Before the crisis, we had five black people here, everyone knew them and people would help them go back to their countries two times a year," Vespignani said. "Everyone knew what they were doing. Ever since that number went exponentially higher, something felt wrong."

With thousands of new arrivals every month, more Italians are starting to rebel, and they are driving their leaders to pursue once-unthinkable solutions to halt the flow.

Those efforts include empowering the Libyan coast guard - an anarchic, often corrupt force - to return migrants to detention camps on Libyan soil where inmates face forced labor, torture and rape; imposing tough new rules on charity-run rescue ships, thus making their missions more difficult; and pursuing administrative action against Italians, such as the priest, who help under-the-radar migrants.

Former center-left prime minister Matteo Renzi, who hopes to recapture office in elections due no later than spring 2018, embraced the shift when he endorsed an approach to migration once held mainly by Italy's far right. He caused a stir when he proclaimed last month that Italy should help potential migrants in their home nations, echoing language used by advocates of extreme anti-migrant policies.

Comment: What a novel idea - help them stay at home rather than become homeless in Italy!

Renzi's move came after June's local elections, which were a hammer blow to his allies across Italy. Anti-migrant politicians surged, while Renzi's left-wing partners lost power in areas that had voted for them for generations, including Pistoia.

Migration "is an issue that will last 20 years," Renzi told an Italian radio station this month.

Inside the grand brick palazzo that has been home to Pistoia's city government since the 14th century, the new mayor, Alessandro Tomassi, is quickly toughening the approach to migration. He cracked down on loitering in the Piazza della Resistenza, a sun-beaten park where some of the city's 188 official asylum seekers, many of them forbidden to take up work, pass the time. And he put the construction of the reception center on hold, saying that it did not have the proper permits.

Italy's center-left leaders "are paying for their top-down, elitist approach to migration," said Tomassi, 38, who before the election was a local councilor who worked at his family's bakery.

The migrant-friendly leaders "are detached from reality," Tomassi said. "They don't know what the people actually think."

Unlike the major 2015 spike in people traveling from Turkey into Greece, where most were Syrians and Iraqis, most of Italy's arrivals come from sub-Saharan Africa, and not all of them are fleeing war. This year, top origin nations include Nigeria, Guinea and Ivory Coast, along with Bangladesh.

As of Friday, 96,930 migrants had arrived in Italy this year, down 3.9 percent compared with the same period last year. Far fewer have

In Pistoia, northwest of Florence, the local political campaign was upended shortly before the June elections by a rebellion against a planned migrant reception center in Nespolo, the tiny neighborhood where Pani grew up. Many residents immediately turned against it - and they and many others credit the new mayor's upset win to their anger.

The proposed building, a long-vacant clinic with barred windows, is a poor place to turn into a home for 24 asylum seekers, they say. And the residential area, nearly completely devoid of businesses and poorly connected to the center of town, offers little for migrants to pass the time.

"We have a lot of young people who are going to the United States or somewhere else because there's no work," said Sergio Sebastiani, 40, a member of a local group campaigning against the reception center. "And here you have people who have no education, no qualifications. What are they going to do here?"

One of the city's former leaders blames her loss on migration.

"In a global age, mixing is a natural perspective for our countries," said Daniela Belliti, the former deputy mayor who was voted out in June. She was giving voice to a perspective once typical of the city's leftist political scene. Pistoia lived through an earlier migration wave in the 1990s, when tens of thousands of Albanians fled the ashes of communism and sailed across the Adriatic to Italy. Many settled here.

Comment: In an age of global war the 'mixing' becomes that much more chaotic and dangerous.

"Pistoia is a city that is hospitable to the left wing," Belliti said. "But there are many concerns about the lack of jobs, the lack of future for youth. There is widespread uncertainty that serves as fertile soil for people trying to find scapegoats."

The town's tensions are on easy display to its migrants.

"Here, they don't like blacks," said Kone Yacouba, 24, who arrived in Pistoia last October after a trek from his native Ivory Coast. "They said it was a country with rule of law, but they won't even take you at a clinic. And if you get onto a bus, everyone looks at you strangely."

He said he had been turned away from a hospital when he needed medical attention for eye problems and a skin condition. And he said that the facility where he is staying is pocketing public funds instead of offering food to its residents.

But many Pistoians have also dedicated themselves to the crisis, including a priest, Massimo Biancalani, who has thrown open his church doors to a group of largely Muslim migrants. About 30 young men stay in the church's warren of outbuildings at any one time. Not all of them are legally registered in Italy, and last month he was fined about $380 for failing to notify authorities within 48 hours that he had taken in a 26-year-old Ghanaian man.

"This law creates more invisible people, whose only crime was asking for help. As a priest, I am called to help people when they ask for it," he said. "Pistoia reflects the general climate of mistrust and fear. But the more you know these guys, the greater your perception of their humanity."

Biancalani wrote a letter to the leaders of the group protesting the new migrant center, asking them to be sympathetic to those in need. He didn't hear back.

Near the proposed site, Pani sat one recent sweltering evening at a community center her father now runs. She said that despite her longtime involvement in left-wing politics, she could barely recognize the help-migrants-in-Africa sentiments of Renzi, let alone the attitudes of her family's neighbors.

Pani said she had struggled for years to find full-time work - but she said that, despite Italy's stubbornly high youth unemployment rates, it didn't make sense to view the migrants as competition.

"The jobs we are looking for in Italy are not the ones they are looking for," she said. "They're not stealing a job from me."

But Pani's disagreements aren't just with the neighborhood - they extend to her family.

Her father, Renato, 71, was an elected leader in the city in the mid-1990s, just as the Albanians were arriving. Now he runs a community center tied to a left-wing local organization. Migration makes the town richer, he said, and he was firm that his commitment to that idea has not slackened.

Still, he said with a pained smile, this time it might be better to help people in their own countries.

"We ought to keep helping and receiving people fleeing for humanitarian reasons," Renato Pani said. "And at the same time, we need to put in obstacles to the business of the flow."

"People looking for a job ought to be able to find one in their own countries," he said, "rather than looking for them in countries like ours, where we struggle to find places for our own people."

Comment: For more on the myriad problems Europe faces in the coming years, check out:

The Truth Perspective: Weapons of Mass Migration: Interview with Michael Springmann on Europe's Migrant Crisis