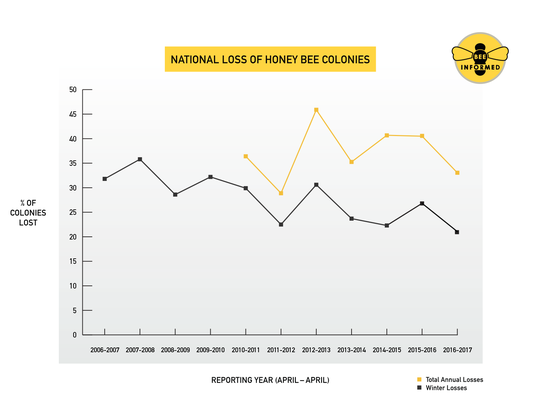

The annual survey of roughly 5,000 beekeepers showed the 33% dip from April 2016 to April 2017. The decrease is small compared to the survey's previous 10 years, when the decrease hovered at roughly 40%. From 2012 to 2013, nearly half of the nation's colonies died.

"I would stop short of calling this 'good' news," said Dennis vanEngelsdorp, an assistant professor at the University of Maryland. "Colony loss of more than 30% over the entire year is high. It's hard to imagine any other agricultural sector being able to stay in business with such consistently high losses."

The research, published Thursday, is the work of the nonprofit Bee Informed Partnership and the Apiary Inspectors of America.

That causes beekeepers to charge farmers more for pollinating crops and creates a scarcity of bees available for pollination. It's a trend that threatens beekeepers trying to make a living and could lead to a drop-off in fruits and nuts reliant on pollination, vanEngelsdor said.

One in every three bites of food, van Engelsdorp said, is directly or indirectly pollinated by honeybees, who pollinate about $15 billion worth of U.S. crops each year. Almonds, for instance, are completely reliant on honeybee pollination.

"Keeping bees healthy is really essential in order to meet that demand," said vanEngelsdorp. He said there are concerns it won't.

So what's killing the honeybees? Parasites, diseases, poor nutrition, and pesticides among many others. The chief killer is the varroa mite, a "lethal parasite," which researchers said spreads among colonies.

"This is a complex problem," said Maryland graduate student Kelly Kulhanek, who assisted with the study. "Lower losses are a great start, but it's important to remember that 33% is still much higher than beekeepers deem acceptable. There is still much work to do."

vanEngelsdorp said people can do their part to save bee colonies by buying honey from a local beekeeper, becoming a beekeeper, avoiding using pesticides in your yard and making room for pollinators, such as honeybees, in your yard.

"Bees are good indicators of the landscape as a whole," said Nathalie Steinhauer, who led data collection on the project. "To keep healthy bees, you need a good environment and you need your neighbors to keep healthy bees. Honeybee health is a community matter."

I hate my neighbors