OF THE

TIMES

A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual doom.

(Communications/Transportation Mercury Retrograde in Aries changed to forward motion conjunct the Nodes of Destiny simultaneously with our Scorpio...

Harari said, he and the likeminded cabal of shadowy world masters will "build an Ark and leave the rest to drown." Moonraker [Link]

With each such step we come closer to the fulfillment of Irlmaier's prophecy.

A once "prosperous" country has been ruined by its leaders and "oligarchs," the Belarusian president has claimed Yes, it is true; and the reason...

A precedent has been set, at least in the minds of property owners along the border.

To submit an article for publication, see our Submission Guidelines

Reader comments do not necessarily reflect the views of the volunteers, editors, and directors of SOTT.net or the Quantum Future Group.

Some icons on this site were created by: Afterglow, Aha-Soft, AntialiasFactory, artdesigner.lv, Artura, DailyOverview, Everaldo, GraphicsFuel, IconFactory, Iconka, IconShock, Icons-Land, i-love-icons, KDE-look.org, Klukeart, mugenb16, Map Icons Collection, PetshopBoxStudio, VisualPharm, wbeiruti, WebIconset

Powered by PikaJS 🐁 and In·Site

Original content © 2002-2024 by Sott.net/Signs of the Times. See: FAIR USE NOTICE

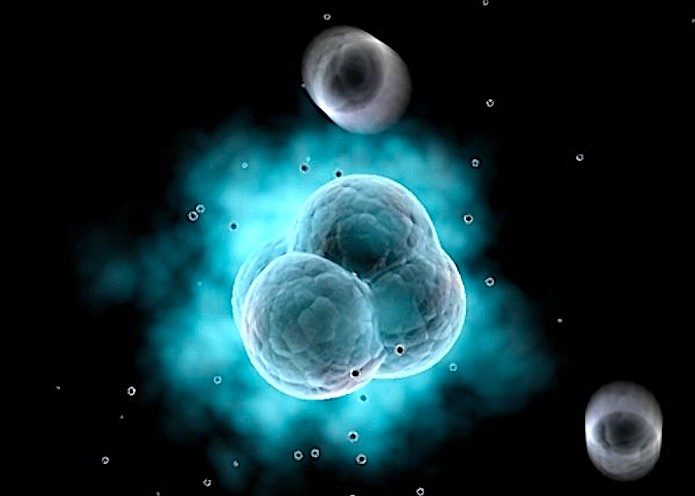

Comment: There are between1078 to 1082 atoms in the known, observable universe. In layman's terms, that works out to between ten quadrillion vigintillion and one-hundred thousand quadrillion vigintillion atoms. If we can store our data on an atom...best not to lose it.