Accidentally, Onfim created fascinating archaeological data which was discovered centuries after he lived. This unintentional time capsule has provided a unique insight into life in Medieval Novgorod.

Onfim was a six or seven-year-old boy who preserved his personal messages, IOUs, love letters, shopping lists, syllables, notes, and homework in the clay soil of Novgorod. He also kept his drawings which depicted everyday experiences such as fights between him and his teacher.

Onfim's notes are valuable because of their childish honesty which describes the life in Medieval times impartially and can be studied as social history. Most records of the past are the writings of politicians, theologians, and historians, but children's preserved work tells more about the life of "actual" people.

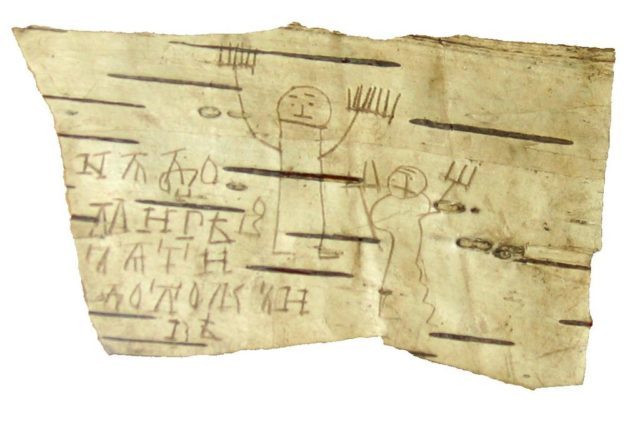

The collection consists of seventeen birch bark items of which twelve are illustrations with text, and the remaining five contain only text. Scholars have studied the amusing collection and analyzed Onfim's work.

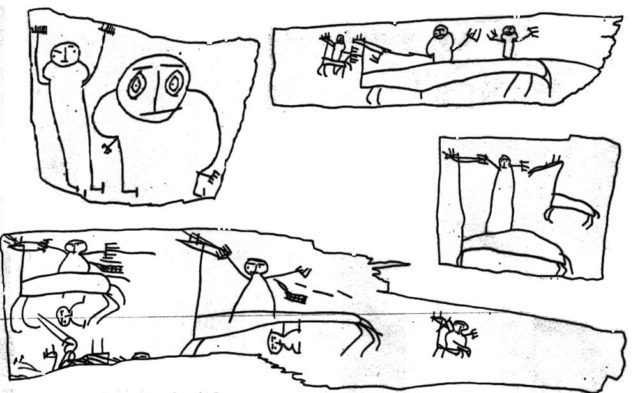

In one of them, he had illustrated a knight on a horse, stabbing someone on the ground with a lance and it was concluded that Onfim drew himself as a knight.

Most of the preserved work is part of his homework - he had practiced the alphabet and had written psalms including phrases such as "Lord, help your servant Onfim" and fragments from Psalms 6:2 and 27:3. Most of his work contains citations from the Book of Psalms.

The boy left drawings of knights, horses, arrows, and slain enemies, and apparently, he liked to illustrate people more than anything else.

On one of the drawings he had illustrated himself, his mother, and father, while on another one he had drawn a portrait of himself as a fantastic animal. There is also one of the children playing around a tree, while one of them is hidden behind the tree.

There are notes on the illustrations, one saying "I am a beast" and another "Greetings from Onfim to Danila." He had also illustrated his father and written "This is my Dad!

He is a warrior. When I grow up, I want to be a warrior just like him!" We hope that he did and that he was a happy knight when he grew up.

Where Mud Is Archaeological Gold, Russian History Grew on Trees

The city of Novgorod was founded, according to legend, by Rurik, a Varangian chieftain, in 859. It is a place where democracy once flourished, where benevolent princes ruled with the consent of a parliament of local elites called the Veche, where markets hummed and international trade thrived, where women were empowered to participate in business and other aspects of public life.

It was a place where children began attending school around the year 1030. Among the most poignant of the birch documents are writings by a boy named Onfim, believed to be 6 or 7 years old. Dated to around 1260, they included school exercises and doodles. In one drawing, Onfim seems to envision himself as a warrior, writing his own name next to a figure on horseback who has slain an adversary. In another, there is a four-legged creature with a tail, and the words, "I, beast."

In an interview in his office, the city's mayor, Yuri I. Bobryshev, glowed with pride as he described its history as a major trading post of the medieval Hanseatic League, with strong ties to the European centers of Lubeck, Bruges, Ghent and London.

"It was a union of merchants and the decisions taken by that union were unconditionally carried out by the rulers of all European states," Mr. Bobryshev said, adding with a sly smile, "Of course, at that time there was no trace of the United States."

The city and its outskirts are dotted with excavation sites, including the Troitsky dig, which has been underway since the 1970s. The first birch-bark scrolls were found in 1951. At the huge pit on Bolshaya Moskovskaya Street, which yielded some of the most important finds this summer, Mr. Yazikov bounded down a ramp, descending through hundreds of years of Russian history (with every few steps). Small white pieces of paper marked the layers in the soil corresponding to the different centuries.Coins, seals and jewelry point to a merchant's home being on the site for much of its history.

There is evidence that in the 10th century the area was mostly used for gardens and an apple orchard. In the 12th century, the city was flourishing, with evidence of large wooden buildings. Experts say the wet, clay soil that lies under Novgorod, and contains little or no oxygen, has the unusual chemical quality that preserves both hard artifacts made of metal and items made of softer material like leather."It is revolutionary in the sense that it gives you inside knowledge of a medieval city that had international ties with the East and the West, how it was organized and functioned, and how people communicated with each other," he said. The birch-bark documents date from the 1000s through the 1400s, when paper became more readily available.

Source: NYT

Comment: See also: