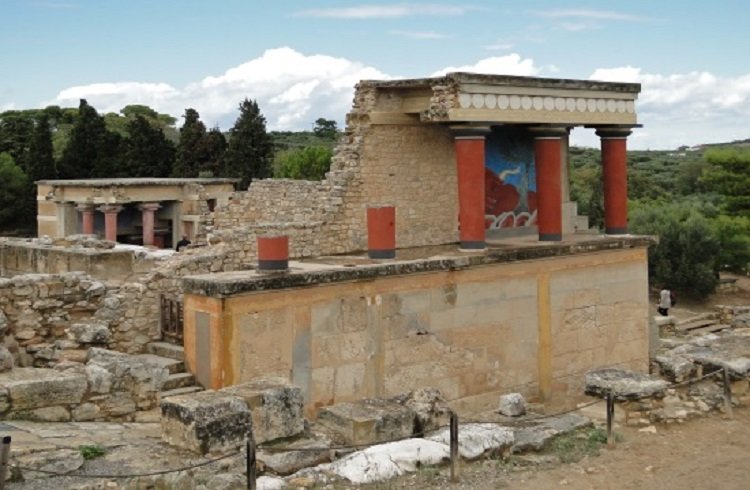

Scientists already knew that Knossos was Europe's oldest city and ruled over the massive trade empire during the Bronze age, nevertheless, new evidence suggests that the Minoans may have actually survived into the Iron Age.

Europe's oldest city, the majestic site of the Greek Bronze Age, was the seat of power of the mythological King Minos and the home of the enigmatic labyrinth. Also linked to far reaching legends like Daedalus and son Icarus, the Minoan palace and the Minoans were also considered to be the sons and daughters of Atlantic by the ancients. This civilization is widely acclaimed as the birthplace for all western civilization and, when the mainland Greeks came out of the Stone Age, the Minoans managed a maritime empire across the entire Mediterranean basin and beyond. When Rome was not even so much as an idea, Minoans built the first paved roads.

Even though the ancient city was previously thought to have perished around 1200 B.C. after the volcanic eruption of Thera on Santorini, new artifacts discovered by a team led by a University of Cincinnati assistant professor of classics, Antonis Kotsonas, suggest that it was much larger and richer than was previously thought.

According to a press release on Kotsonas' work, "recent fieldwork at the ancient city of Knossos on the Greek island of Crete finds that during the early Iron Age (1100 to 600 BC), the city was rich in imports and was nearly three times larger than what was believed from earlier excavations.

San Francisco meeting

The discovery suggests that not only did this spectacular site in the Greek Bronze Age (between 3500 and 1100 BC) recover from the collapse of the socio-political system around 1200 BC, but also rapidly grew and thrived as a cosmopolitan hub of the Aegean and Mediterranean regions. Antonis Kotsonas, a University of Cincinnati assistant professor of classics, will highlight his field research with the Knossos Urban Landscape Project at the 117th annual meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America and Society for Classical Studies. The meeting takes place Jan. 7-10 in San Francisco.

The Knossos Urban Landscape Project over the past decade has recovered a large collection of ceramics and artifacts dating back to the Iron Age. The relics were spread over an extensive area that was previously unexplored. Kotsonas says that this exploration revealed considerable growth in the size of the settlement during the early Iron Age and also growth in the quantity and quality of its imports coming from mainland Greece, Cyprus, the Near East, Egypt, Italy, Sardinia and the western Mediterranean.

"No other site in the Aegean period has such a range of imports," Kotsonas says. The imports include bronze and other metals - jewelry and adornments, as well as pottery. He adds that the majority of the materials, recovered from tombs, provide a glimpse of the wealth in the community, because status symbols were buried with the dead during this period.

The antiquities were collected from fields covering the remains of dwellings and cemeteries. "Distinguishing between domestic and burial contexts is essential for determining the size of the settlement and understanding the demographic, socio-political and economic development of the local community," explains Kotsonas. "Even at this early stage in detailed analysis, it appears that this was a nucleated, rather densely occupied settlement extending over the core of the Knossos valley, from at least the east slopes of the acropolis hill on the west to the Kairatos River, and from the Vlychia stream on the south until roughly midway between the Minoan palace and the Kephala hill."

Research partnership

Kotsonas' Jan. 9 presentation is part of a colloquium themed, "Long-Term Urban Dynamics at Knossos: The Knossos Urban Landscape Project, 2005-2015." Kotsonas serves as a consultant on the project, which is dedicated to intensively surveying the Knossos valley and documenting the development of the site from 7000 BC, to the early 20th century. The project is a research partnership between the Greek Archaeological Service and the British School at Athens. Kotsonas has served as a collaborator on the project since 2009.

Funding for the University of Cincinatti research was supported by the UC Department of Classics Louise Taft Semple Fund.

Kotsonas underlines that because the site also is a popular tourist attraction, there is a strong interest in development around the site. The Knossos Urban Landscape Project works to inform the community about the importance of preserving the area that has history yet to be uncovered, history that could be lost if future development destroyed unexplored parts of the site.

The AIA and SCS Joint Annual Meeting brings together professional and vocational archaeologists and classicists from around the world to share the latest developments from the field. The conference is the largest and oldest established meeting of classical scholars and archaeologists in North America.

UC's Classics Department in the McMicken College of Arts and Sciences is one of the most active centers for the study of the Greek and Roman Antiquity in the United States. UC excavations have been led at two Bronze Age palatial centers, Knossos in Crete, and Pylos in the Peloponnese, a site first discovered by UC archaeologist Carl W. Blegen in 1939.

Can there be more photos of these things?