But to the great bewilderment of scientists, the epidemic has not produced the wave of fetal deformities so widely feared when the images of misshapen infants first emerged from Brazil.

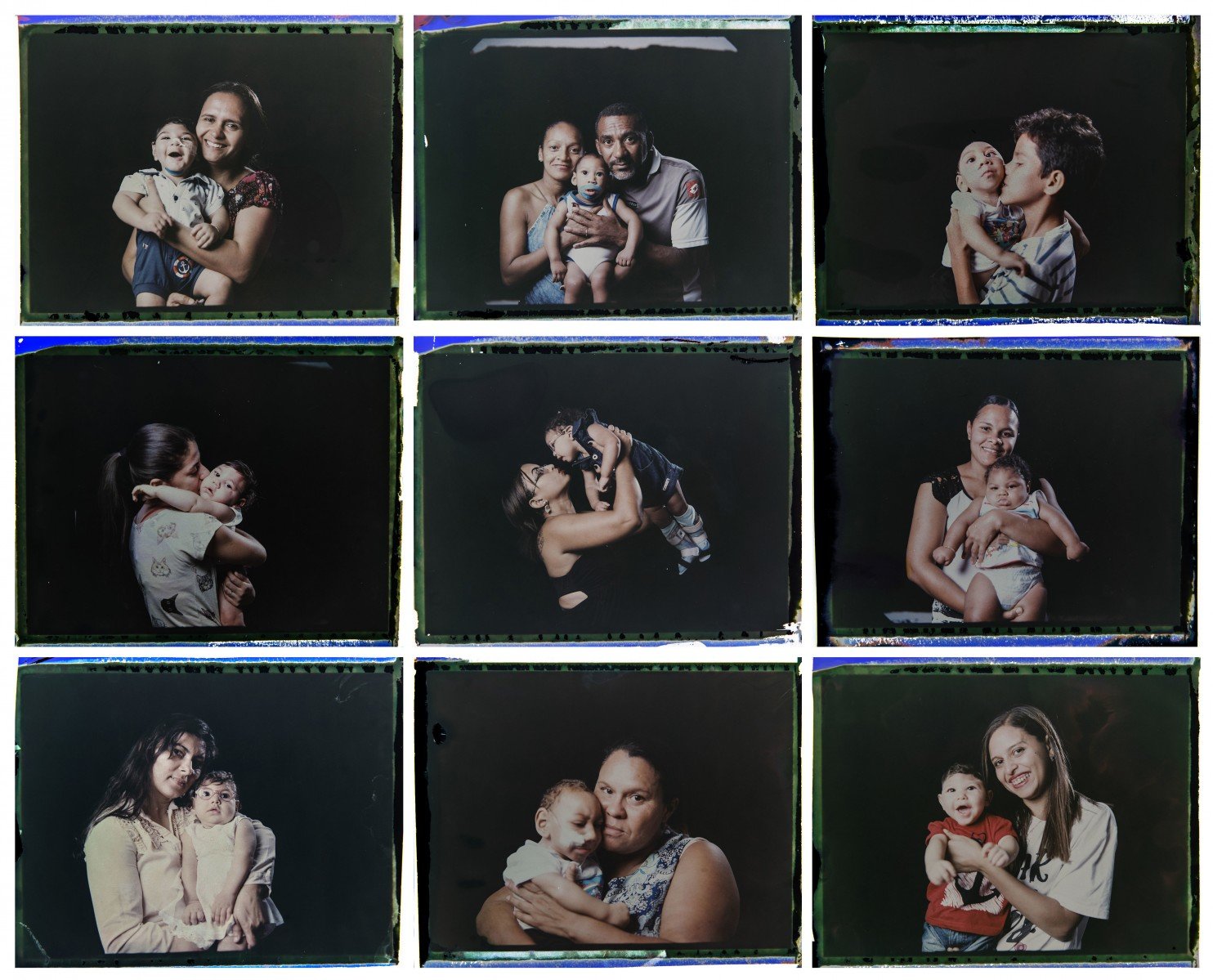

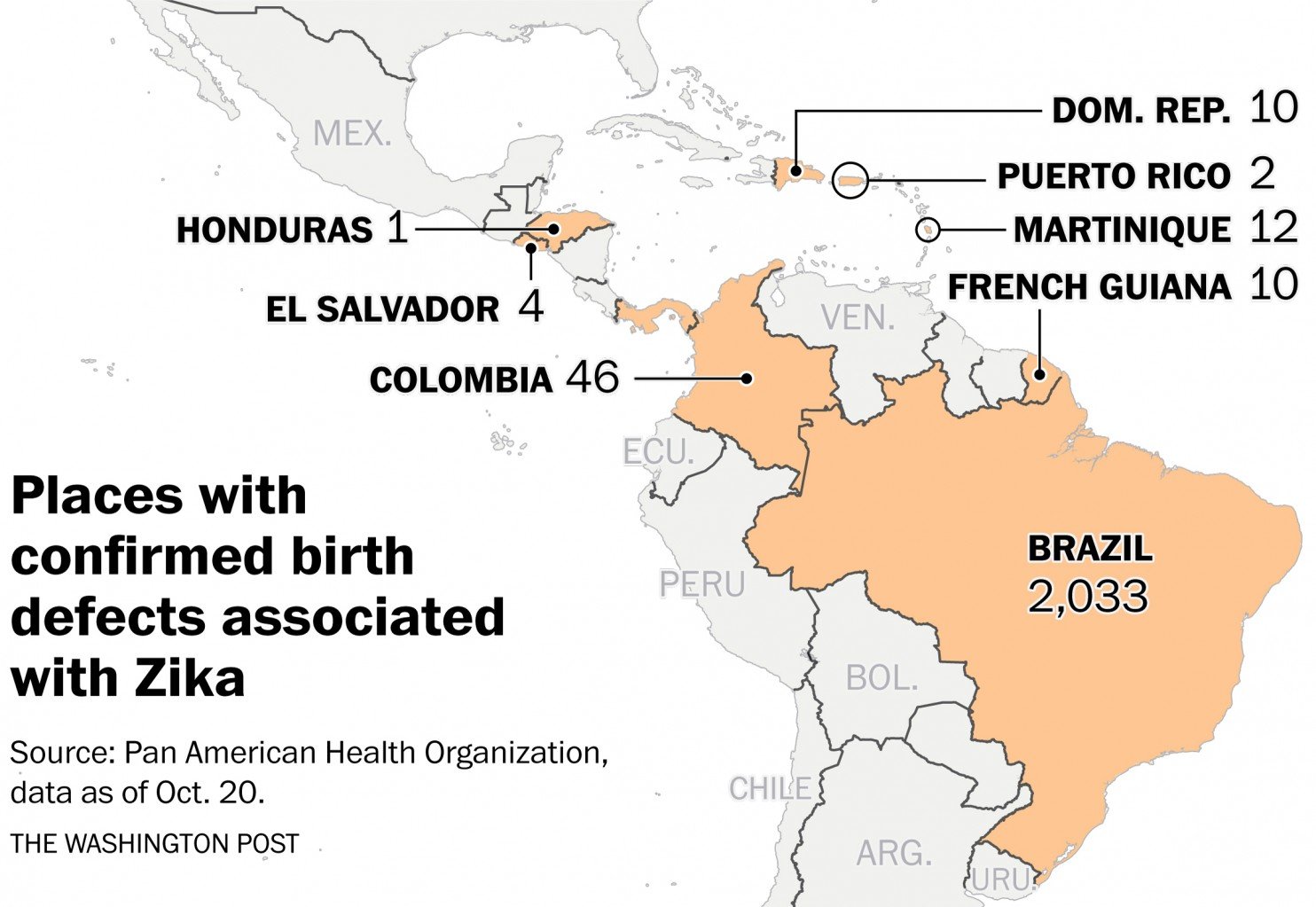

Instead, Zika has left a puzzling and distinctly uneven pattern of damage across the Americas. According to the latest U.N. figures, of the 2,175 babies born in the past year with undersize heads or other congenital neurological damage linked to Zika, more than 75 percent have been clustered in a single region: northeastern Brazil.

The pattern is so confounding that health officials and scientists have turned their attention back to northeastern Brazil to understand why Zika's toll has been so much heavier there. They suspect that other, underlying causes may be to blame, such as the presence of another mosquito-borne virus like chikungunya or dengue. Or that environmental, genetic or immunological factors combined with Zika to put mothers in the area at greater risk.

"We don't believe that Zika is the only cause," Fatima Marinho, director of the noncommunicable disease department at Brazil's Ministry of Health, said in an interview.

Brazilian officials were bracing for a flood of fetal deformities as Zika spread this year to other regions of the country, Marinho said. However, "we are not seeing a big increase."

Researchers and health officials remain cautious about the lower-than-expected numbers. The latest studies have found more evidence than ever that the virus can inflict severe damage on the developing infant brain, some of which may not be evident until later in childhood.

But researchers so far have learned a lot more about Zika's potential to do harm than its likelihood of doing so.

Scientists at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are closely watching Puerto Rico, which has reported more than 26,800 cases of Zika. More than 7,000 pregnant women could be infected by the end of the year, according to the CDC.

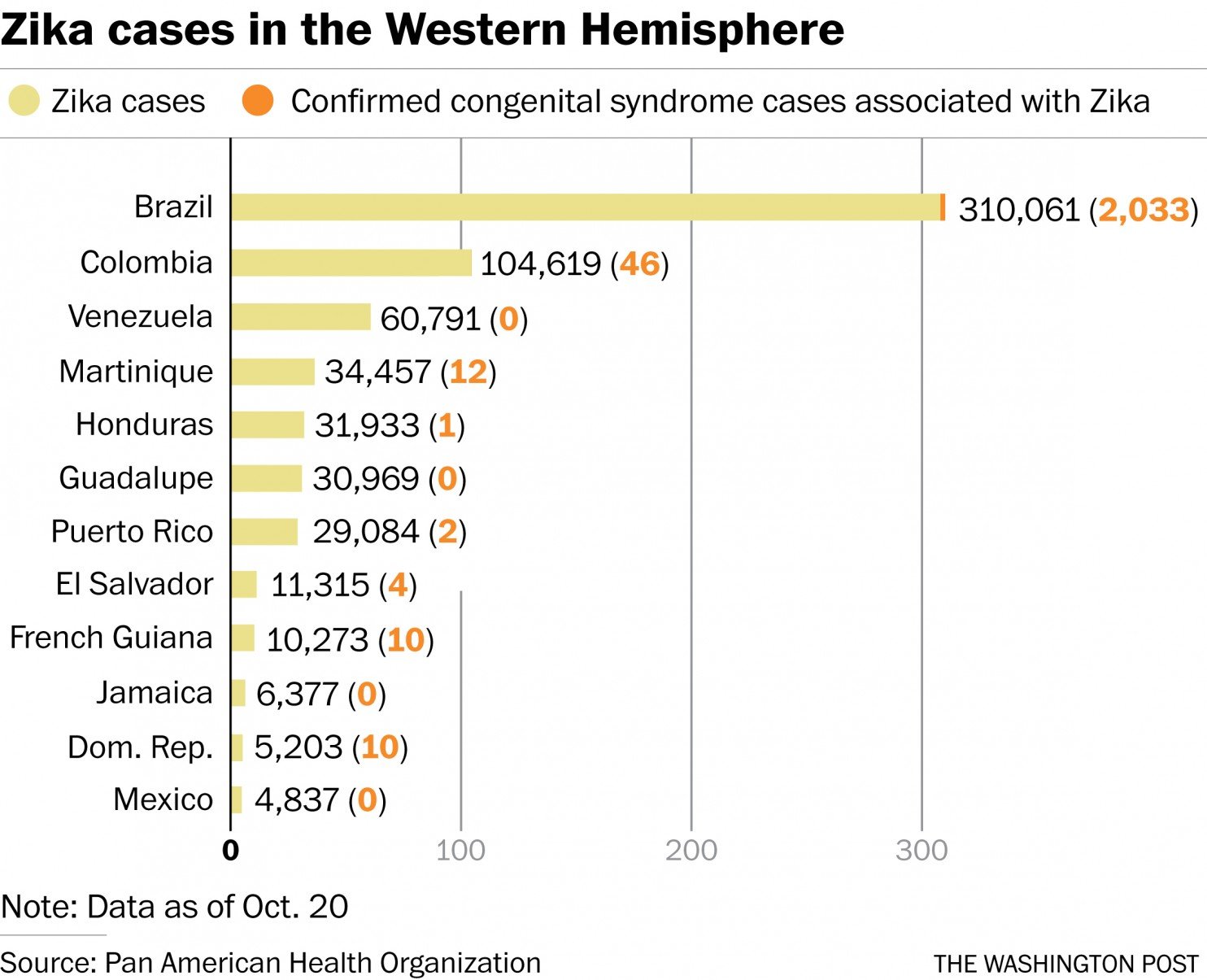

But although the outbreak has spread this year to more than 50 nations and territories across the Western Hemisphere, U.N. data shows just 142 cases of congenital birth defects linked to Zika so far outside Brazil.

In Colombia, praised for some of the most rigorous standards for detecting and monitoring Zika, the government has tallied more than 104,000 Zika cases, including nearly 20,000 pregnant women. It has the second-highest number of Zika infections in the world after Brazil.

But so far, Colombia has had just 46 babies born with congenital nervous system damage linked to Zika. And the number of new Zika cases in Colombia has fallen so sharply that the government in July declared the epidemic over, saying the virus will remain a threat but no longer spread rampantly.

Colombia is investigating 332 more cases of birth defects for a possible Zika link, but health officials there had been prepared for many more.

"Our focus on Zika has changed," said Ernesto Marques, an epidemiologist at the University of Pittsburgh who is working on a project to develop a vaccine for the virus.

Marques is from Recife, the city in northern Brazil hit hardest by the Zika outbreak, and he was part of the team that first identified the virus as a possible culprit when deformed infants began showing up "almost every day" in Recife's maternity wards at this time last year.

At the time, Marques said scientists were focused on identifying Zika as a "causal agent" for the sudden increase in birth defects, especially microcephaly, in which babies are born with undersize heads and often calcified brain tissue.

"Now we've settled on Zika as the smoking gun, but we don't know who pulled the trigger," said Marques, speaking from Recife, where he is working with government researchers.

One of the leading theories, said Marques, is that northeastern Brazil's last dengue outbreak was in 2003 — relatively long ago — so perhaps mothers in the area had relatively fewer antibodies to cope with Zika, which is spread by the same mosquito.

"Sexual habits and hygiene may also play a role," he said, explaining that researchers are looking at whether sexual transmission can infect the uterus and placenta with the virus, potentially exposing the fetus to elevated risk.

"We suspect the villain has an accomplice, but we don't know who it is," Marques said.

Many question marks

Researchers caution that it will take years to fully identify the dangers Zika poses to babies' brains, and microcephaly is just one threat from the virus. A Zika infection poses the greatest danger toward the end of the mother's first trimester of pregnancy, and its harmful effects on fetal development may not be apparent at birth or manifest themselves until later in childhood.

Marcos Espinal, the director of communicable diseases and health analysis at the Pan American Health Organization, said U.N. health officials were right to put the world on high alert earlier this year because so little was known about Zika.

"If you don't know about something, you better take preventative measures to minimize the risks," Espinal said. "So maybe the fact that we don't have a lot of microcephaly means that we were doing our jobs" and helped women avoid infection.

At the peak of Zika alarm earlier this year, several Latin American countries urged women to delay pregnancy. El Salvador's government recommended waiting two years. The widespread anxieties produced by the outbreak may have led to an increase in abortions in Latin America, a region where the procedure is widely banned. Anecdotal evidence suggests more women have been quietly terminating pregnancies over worries that their babies might be deformed.

This may also help explain the relatively low number of babies born with Zika-related birth defects outside northeast Brazil.

"It is very difficult to work out truly what is going on," said Oliver Brady, an epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine who has been working with the Brazilian government on Zika.

Until last year, Brazil reported about 150 cases annually of microcephaly, a condition that can also be caused by diseases like herpes and syphilis. Claudio Maierovitch, a former senior Brazilian health official responsible for monitoring Zika when the epidemic started, said that the figure was probably an undercount and that around 500 cases of microcephaly a year pre-Zika would be a more accurate number.

When the microcephaly outbreak was first identified in Brazil, spooked health officials erred in the other direction and overdiagnosed the condition. Eventually, nearly 5,000 newborns who had been diagnosed with possible microcephaly turned out to be fine, according to Marinho, the Brazilian health official.

But that still leaves at least 2,000 instances of Zika-related birth defects in the country, with an additional 3,000 cases under investigation.

A big problem in determining whether Brazil has a higher rate of Zika-related birth defects is that no one is sure how many people caught the virus in 2015, when it was little known and widely confused with dengue.

"The fact is we don't have any idea how many cases there were," said Maierovitch, meaning it's possible Brazil's birth-defect totals could simply be a reflection of a Zika outbreak that was far more pervasive than anywhere else.

An eye on U.S. territory

Puerto Rico is the next laboratory for understanding Zika. CDC researchers are watching for Zika-related birth defects on the island, but the mainland United States appears to have averted a major outbreak so far.

The vast majority of cases the CDC has counted were attributed to infections acquired abroad or through sexual transmission, though mosquitoes have spread the virus in a few neighborhoods in and around Miami. Experts have warned, however, that local mosquito-driven outbreaks may be occurring in other parts of the country, particularly in states on the Gulf of Mexico. An estimated 80 percent of people infected with the virus don't have symptoms and don't realize they have Zika.

Comment: CDC using the Zika virus to justify forced vaccinations, quarantines and mass aerial spraying

Peter Hotez, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, said Congress's failure to approve Zika funding this year means there was no effective way to accurately count how many people were infected.

"We'll have to hold our breath to see what happens in labor and delivery suites in a few months," he said. "That's the only way we'll know whether we've dodged a bullet."

Comment: Don't let the Zika virus hype scare you. More articles on this mysterious virus: