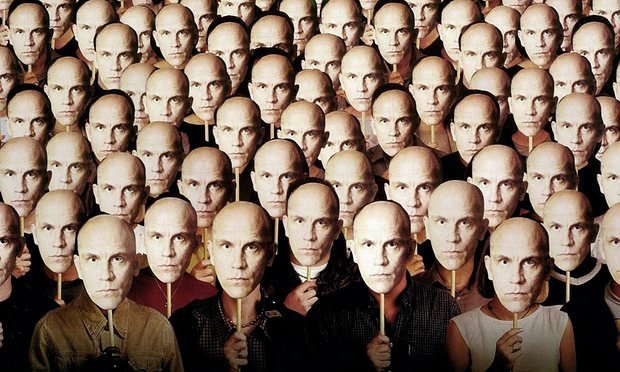

Roger Waters of Pink Floyd called it "the lunatic in my head". He was describing the endless stream of internal thoughts and sensations - the inner voice - that we try to weave into a coherent story called "my life". The trouble is, this chattering narrator often gets things wrong, mixing biased reporting with snap judgments and old insecurities with unwarranted dread.

For instance, your first thought may be blandly factual. "I just had dinner with my in-laws" or "I have a project due on Monday." But within seconds that innocent thought has morphed into "My in-laws hate me" or "My job is going down the tubes" or "What waistline?! I look like a walrus!"

The mind gets stuck in ruts - taking shortcuts and jumping to conclusions - because shortcuts and familiar patterns makes life more manageable. "Mary had a little ___." Lamb, right? The word popped into your head automatically, which is how so many of our mental constructs come to be.

Our problems begin when we accept as fact these unexamined, automatic thoughts, based on biases, old hurts, or assumption, all of them ramped up with a Technicolor intensity. The enhanced production values come along in part because the brain region that makes these judgments, and the region that processes sensory inputs, are adjacent - which makes it all too easy for a trumped-up worry or pointless regret to take on the look and feel of an entirely realistic scenario: "I'm going to get sacked! I'll be homeless and sleeping over a heating grate! I can feel the snow drifting down my collar!"

Anxieties, fears and regrets don't have to control our behaviour or mood. We're the thinker, not the thoughtThis blend of cognitive and sensory processing is an evolutionary adaptation that served us well when snakes and lions were daily threats. Our ancient ancestors needed to feel danger viscerally, getting the "Watch out!" message in a way that led immediately to the endocrine system's fuel-injection process: the freeze-or-fight-or-flight response. But coping with today's abstract anxieties and resolving yesterday's wounds - easily exaggerated and sustained in an endless loop by that lunatic in our head - is not helped by vivid imagery.

So what's the answer? Research shows that it's counterproductive to try to silence the voice (tell yourself not to think about a pink elephant and see what happens) or to "fix" the negative thoughts, or to forcibly replace them with "happy" ones. What works is to develop the emotional agility that gets beyond rigid "autopilot" responses and puts more of our genuine selves in charge.

We do this by showing up "the lunatic" and accepting the negative thoughts - the anxieties, fears, regrets - for what they are: thoughts. They're not directives, and they're not "us". By acknowledging that they're here to stay, we make peace with them, which creates a distance from them - a recognition that they don't have to control our behaviour or our mood. They're more like clouds passing by, or options presented by our "staff". We're the ones - the thinker rather than the thought - who get to choose the actions that will best serve the life we want to live and the things we truly value.

This is the path suggested by Viktor Frankl in his moving analysis of the Holocaust, Man's Search for Meaning:

"Between stimulus and response there is a space... In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom."About the author

Susan David will give a masterclass at Conway Hall in London on 11 April (conwayhall.org.uk). Her book Emotional Agility: Get Unstuck, Embrace Change, and Thrive in Work and Life (Penguin Life, £14.99, or £11.99 atbookshop.theguardian.com) is out now

Reminds me of....emotional flexibility!