But it took an East Coast magazine to finally elevate the issue onto the White House agenda.

Inspired in large part by an article in The New Yorker in the summer, the Obama administration is hosting an Earthquake Resilience Summit on Tuesday — and is expected to underscore its support for an earthquake early warning system on the West Coast.

It's not clear whether that support will come with additional federal money, but foundations and some Northwest businesses will announce contributions to a warning system.

The event will be streamed live beginning at 9:30 a.m. PST.

The article that kicked things off was published in the July 20 edition of the weekly magazine, which once ran a map on its cover showing the entire Western U.S. dwarfed by a few midtown intersections, reflecting a Manhattan-centric world view.

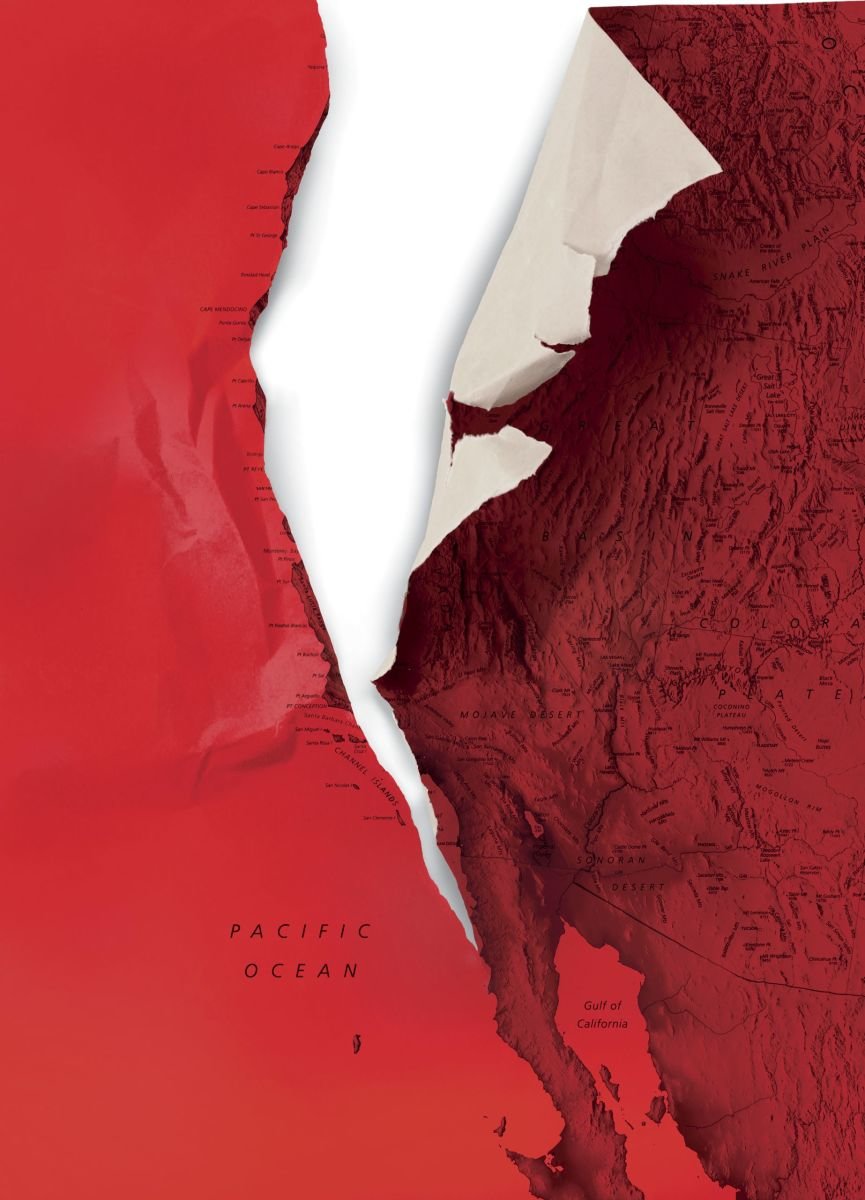

In "The Really Big One," author Kathryn Schulz — a former Oregonian — dramatically described the impact of a magnitude 9 earthquake and tsunami from the Cascadia Subduction Zone, a 700-mile-long fault off the Northwest Coast. One of the more hair-raising quotes was from a FEMA official who said "our operating assumption is that everything west of Interstate 5 will be toast."

The story shocked many Northwesterners and people in other parts of the country who had no idea California wasn't the only earthquake-prone state. Schulz was flooded with so many panicked messages and questions that she wrote a follow-up piece offering preparedness tips and more details on the meaning of "toast."

The article also shook things up in the West Wing, said John Schelling, earthquake and tsunami manager for the Washington Emergency Management Division, who participated in conference calls planning the summit.

"It really caught their attention, along with a lot of other information that had been circulating, and they were interested in having an event to talk about earthquake early warning and other key issues, like building codes," he said.

Early warning systems detect the initial seismic waves from an earthquake at a distance and transmit alerts that arrive seconds to minutes before strong shaking starts. In Japan, which has the world's most advanced system, the alerts shut down machinery, open elevators and bring bullet trains to a halt. Warnings are distributed to the public via cellphone, giving people time to take cover, climb off ladders and evacuate dangerous areas.

But, as The New Yorker article pointed out, the U.S. has no such system in operation.

A prototype developed by scientists in California and at the University of Washington is being tested.

With support from Sen. Patty Murray and Rep. Derek Kilmer, whose district includes Tacoma, Bremerton and the Olympic Peninsula, funding for the system was bumped up to $8.2 million for 2016. But fully implementing it will cost up to $38 million for new instruments, and $16 million a year for operations.

Though that level of funding hasn't materialized, the White House event will give the program a boost, said John Vidale, director of the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network at the UW.

"Nothing is guaranteed, but the expectation now is that we will build it," he said. "That's a big step from where we were."

The half-day event will include several panel discussions and announcements.

A key organizer has been Jacqueline Meszaros, of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy.

Meszaros is well-versed in Northwest seismic hazards. As a risk-management specialist and former professor at UW Bothell, she analyzed the 2001 Nisqually quake's impact on small businesses and co-authored a scenario for a Seattle Fault quake.

Local emergency managers remain bemused by the reach of The New Yorker article, but grateful that it shined a national spotlight on the threat.

"It's exciting that it's captivated attention in places like the White House," Schelling said. "Coming from a source on the East Coast, I think it helped put on the radar that there is more to seismic hazard in the Western U.S. than the San Andreas Fault — and we need to really pay attention to it."

I opened the front door and there before me was the ocean, it was not far off, but not such as to be at the doorway.

Yes, this has been foreseen and they know as they already do about many other events.