On September 28, while addressing the UN General Assembly, Putin proposed "implementing naturelike technologies, which will make it possible to restore the balance between the biosphere and the technosphere." It is necessary to do so to combat catastrophic global climate change, because, according to Putin, CO2 emissions cuts, even if implemented successfully, would be a mere postponement rather than a solution.

I hadn't heard the phrase "implementing naturelike technologies" before, so I Googled it and Yandexed it, and came up with nothing more than Putin's speech at the UN. He coined the phrase. As with the other phrases he's coined, such as "sovereign democracy" and "dictatorship of the law," it is a game-changer. With him, these aren't words thrown on the wind. In each of these cases, the phrase laid the foundation of a new philosophy of governance, complete with a new set of policies.

In the case of "sovereign democracy," it meant methodically excluding all foreign influences on Russia's political system, a process that culminated recently when Russia, in tandem with China, banned Western NGOs, which were previously making futile attempts to destabilize Russia and China politically. Other countries that find themselves having trouble with the Orange Revolution Syndicate can now follow their best practices.

In the case of "dictatorship of the law," it meant either explicitly legalizing and absorbing into the system, or explicitly outlawing and destroying, every type of illegal or semi-legal social formation, first by focusing on the criminal gangs and protection rackets that proliferated in Russia during the wild 1990s, and now expanding into the international sphere, where Russia is now working to destroy the products of illegal Western activities, such as ISIS, along with other US-trained, US-armed, Saudi-funded terrorist groups. "Dictatorship of the law" means that no-one is above the law, not even the CIA or the Pentagon.

This being a given, it makes sense to carefully parse the phrase, in hopes of gaining a better of understanding of what is meant, and this particular phrase is harder to parse than the previous two, because the Russian original, "внедрение природоподобных технологий", is laden with meanings that English does not directly convey.

"Внедрéние" (vnedrénie) can be translated in any number of ways: implementation; introduction; implantation; inoculation, implantation (of views, ideas); entrenchment (esp. of culture); enacting; advent; launch; incorporation; adoption; inculcation, instillation; indoctrination. Translating it as "implementation" does not do it justice. It is derived from the word "нéдра" (nédra) which means "the nether regions" and is etymologically connected to the Old English word "neðera" through a common Indo-European root. In Russian, it can refer to all sorts of unfathomable depths, from the nether regions of the Earth (where oil and gas are found) to the nether regions of human psyche, as in the phrase "недра подсознательного" (the nether-regions of the subconscious). Translating it with the tinny, technical-sounding word "implementation" does not do it justice. It can very well mean "implantation" or "indoctrination."

The word "природоподóбный" (priródo-podóbnyi) translates directly as "naturelike," although in Russian it has less of an overtone of accidental resemblance and more of an overtone of active conformance or assimilation. It is of recent coinage, and can be found in a few techno-grandiose articles by Russian academics in which they promote vaporous initiatives for driving the development of nanotechnology or quantum microelectronics by simulating evolutionary processes, or some such. The gist of it seems to be that once widgets get too complex for humans to design, we might as well let them evolve like bacteria in a Petri dish.

Based on what Putin said next, we can be sure that this is not what he had in mind: "We need qualitatively different approaches. The discussion should involve principally new, naturelike technologies, which do not injure the environment but exist in harmony with it and will allow us to restore the balance between the biosphere and the technosphere which mankind has disturbed." It seems that he meant that people should conform to nature in daily life rather than try to simulate nature in a laboratory setting.

But what did he mean by "technologies"? Did he mean that we need a new generation of eco-friendly gewgaws and gizmos that are slightly more energy-efficient than the current crop? Again, let's see what got lost in translation. In Russian, the word "tekhnológii" does not directly imply industrial technology, and can relate to any art or craft. Since it is obvious that industrial technology is not particularly "naturelike," it stands to reason that he meant some other type of technology, and one type immediately leaps to mind: political technologies. In Russian, it is written as one word, polittekhnologii, and it is a common one. At its best, it is the art of shifting the common political and cultural mindset in some favorable or productive direction.

Putin is a consummate political technologist. His current domestic approval rating stands at 89%; the remaining 11% disapprove of him because they wish him to take a more hard-line stance against the West. It makes sense, therefore, to examine his proposal from the point of view of political technology, jettisoning the notion that what he meant by "technology" is some sort of new, slightly more eco-friendly industrial plant and equipment. If his initiative succeeds in making 89% of the world's population speak out in favor of rapidly adopting naturelike, ecosystem-compatible lifestyles, while the remaining 11% stand in opposition because they believe the adoption rate isn't high enough, then perhaps climate catastrophe will be averted—or at least its worst-case scenario, which is human extinction.

In the next part of this series, we will learn what political technology is, what sorts of political technologies we can see used all around us. Then we will move on to addressing the main questions: What does it mean for us to become naturelike, and, finally, How can we invent or evolve political technologies to bring about this transformation while there is still time (if we are lucky).

Part 2

Political technologies have three main goals:

1. Changing the rules of the game between participants in the political process.Political technologies pursue these tactical goals in accordance with higher, strategic imperatives, and it is only the noble nature of these higher imperatives that can justify the use of such high-handed, nondemocratic means. Yes, the ends justify the means—once in a while. It is better to save humanity and the natural world through nondemocratic means than to let it go extinct while adhering to strictly democratic ones.

2. Introducing into the mass consciousness new concepts, values, opinions and convictions.

3. Direct manipulation of human behavior through mass media and administrative methods.

But often the imperatives are far less than noble. They can be separated into two kinds:

1. To improve everyone's welfare by pursuing the common good of the entire society, as it is understood by its best-educated, most intelligent, most decent and responsible members. Political technologies of this kind result in a virtuous cycle, building on previous successes to increase social cohesion, solidarity and setting the stage for great achievements. (These are the good kind.)

2. To enrich, empower and protect special interests at the expense of the rest of society. These kinds of political technologies either fail through internal contradiction, or result in a vicious cycle, in which those who benefit from them strive for ever-higher levels of selfish behavior at the expense of the rest, setting the stage for poor social outcomes, economic stagnation, mass violence and eventual civil war and political disintegration. (These are the bad kind.)

Let's take the United States as an example The United States currently has more than its fair share of the latter sort. Let's briefly review a dozen of the most important ones.

1. The fossil fuel lobby. Objective: convince the US population that catastrophic anthropogenic climate change is not occurring. Means: smear campaigns against climate scientists, injection of fake science, denigration of science as a whole, portrayal of the movement to stop catastrophic climate change as a conspiracy, etc. Shows some signs of failing through internal contradiction, as parts of South Carolina—a self-styled "conservative" state—go underwater in a so-called "thousand-year flood" (soon to be renamed a "hundred-year flood," then "ten-year flood" and, finally, a "blub-blub-blub" flood). Unlike North Carolina, Florida (another "blub-blub-blub" state) and Wisconsin, South Carolina hasn't banned the use of the term "climate change" by state workers; not that anyone has heard them use it in any case. When political technologists start banning the use of words, you know that they are becoming desperate. At a meta-polittechnological level, when a polittechnology shows signs of failing through internal contradiction, it is often best to let things run their course. After all, what does it matter whether officials in the Carolinas or in Florida use the term "climate change" or the term "blub-blub-blub"?

Comment: Orlov is partly right here. The US government is denying to the public that catastrophic climate change is occurring. But, it's not anthropogenic global warming that is being hidden, but rather massive earth changes centered on global cooling that humans have some responsibility for, but only in the sense of the human-cosmic connection to earth changes.

2. The arms manufacturers. Objective: convince the US population that private gun ownership makes people safer, is effective in preventing government tyranny, and is a right to be defended at all costs. This too is showing some signs of failure through internal contradiction, as the number of mass shootings in the US shoots up. But the level of brainwash here is rather high, and the US authorities may find themselves forced to resort to direct manipulation to bring the situation under control (or so they would hope). This may involve some sort of mass standoff between the government and the "gun nuts," in which the gun nuts are described as terrorists, outlawed and, in a demonstration exercise, instantaneously wiped out by the army, the navy and the air force. But this would only bring out the next layer of internal contradiction: in decisively demonstrating that owning a gun does not make one safer, and that guns are useless in preventing tyranny, the government would be forced to tacitly admit that it is in fact a tyranny, at war with its own people. And this would undermine a number of other political technologies on which the government depends for its political survival.

3. The two-party political system, along with the lobbyists and its corporate, big-money and foreign sponsors. Objective: keep the people believing that the US is a democracy and that people have a choice. On the one hand, this technology seems to be working. A lot of the people voted for Obama (some of them twice!) and then had a difficult time facing up to the fact that he is an impostor, barely different from his predecessor, and that everything he had said to get their vote was just hopeful noise. And now a lot of these same people are ready to vote again—for some other democratic career politician making similar kinds of hopeful noise. On the other hand, this piece of political technology seems to be in rather sad shape. The party machinery seems unable to produce viable candidates. The Republicans are internally in disarray and seem especially vulnerable to being upstaged by outsiders like Trump. Moreover, most of the voters no longer identify with either party—an unnerving development for political technologists in charge of herding them toward one of the political spectrum or the other.

4. The defense contractors and the national defense establishment. Objective: justify exorbitant defense budgets by claiming that they keep the nation safe by thwarting evildoers or some such nonsense. The US has a very expensive defense establishment, but a very ineffectual one. Case in point: as the hostilities in Syria threaten to escalate, the US orders the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt out of the Persian Gulf, leaving it without a US aircraft carrier there for the first time in 6 years. The reason is simple: although very expensive and impressive looking, American aircraft carriers are only effective against very weak and disorganized adversaries.

When it comes to major powers such as Russia, China and Iran they are no more than sitting ducks, being defenseless against attacks by supersonic cruise missiles and supercavitating torpedoes, which the Americans simply don't have. Such obvious signs of weakness (and there are many others) undermine the claim that defense dollars are money well spent. After a time, the message is bound to sink in that the US defense establishment produces useless military boondoggles and baseless, dreamed-up intelligence reports, resulting in a serious internal contradiction. Couple the relative impotence of American high-tech weaponry against similarly equipped adversaries with the inability or unwillingness to deploy ground troops (after the great "successes" in the meat grinders of Iraq and Afghanistan) and you have an erstwhile superpower whose ability to project force is rather circumscribed. Why, then, does it cost so much? Defeat can be had for a lot less money. A sign of desperation is the latest US initiative to drop palettes of small arms ammunition and hand grenades into the deserts of Northern Syria, hoping that some "moderate" (LOL) terrorist would find them and use them against the Syrian government.

The list goes on but, for the sake of brevity, and as an exercise for the reader, I will let the reader fill in the details about the remaining examples of bad political technologies that are found in the US. The information is not hard to find. Ask yourself whether these technologies will fail through internal contradiction, by triggering a wider conflict, or by causing widespread degeneracy in the population they afflict.

5. The medical industry. Objective: keep people convinced that private health insurance is necessary, that exorbitant medical costs are justified, that socialized medicine is somehow evil, and that they are getting good quality medical care in spite of all evidence to the contrary.

6. The higher education industry. Objective: keep people convinced that higher education in the US is a good value in spite of its exorbitant costs, the student debt crisis, and the fact that over half of recent university and college graduates have been unable to find professional employment.

7. The prison-industrial complex. Objective: keep people convinced that imprisoning a higher percentage of the population than did Stalin, mostly for nonviolent, victimless crimes, somehow keeps people safe, in spite of there being absolutely no evidence of that.

8. The automotive industry. Objective: keep people convinced that the private automobile is the hallmark of personal freedom while denigrating public transportation, in spite of the fact that if you factor in all of the costs and the externalities of private cars and translate them into the working hours it takes to pay for them, driving a car turns out to be slower than walking.

9. The agribusiness industry. Objective: keep people convinced that a diet made up of cheap, chemical-laden, industrially produced food is somehow acceptable in spite of the high levels of obesity, heart disease, diabetes and other ailments in which it results.

10. The financial industry. Objective: keep people convinced that their money is safe even as it disappears into an ever-expanding black hole of unrepayable debt.

11. Organized religion. Objective: keep people convinced that kowtowing to a big white man in the sky, who might send you to hell in spite of the fact that he loves you, and who, in spite of being all-powerful, always needs your money, takes precedence over using your own reason and relying on facts to find your own way in the world. Cause simple-minded people to insist that a worked-over story of the Egyptian god Horus, stuck together with bits of the Gilgamesh Epic and other ancient myths, is the word of God and the absolute literal truth. Keep alive the fiction that religious people are somehow more moral or more ethical than nonreligious people.

12. The legal system. Objective: keep people convinced that the legal system somehow produces justice instead of selling positive outcomes to the highest bidder, that feeding a huge army of well-paid lawyers is somehow worth the money, and that obeying a codex of laws so voluminous and so convoluted that is completely incomprehensible to the average person, and most lawyers, is what it means to be a good citizen.

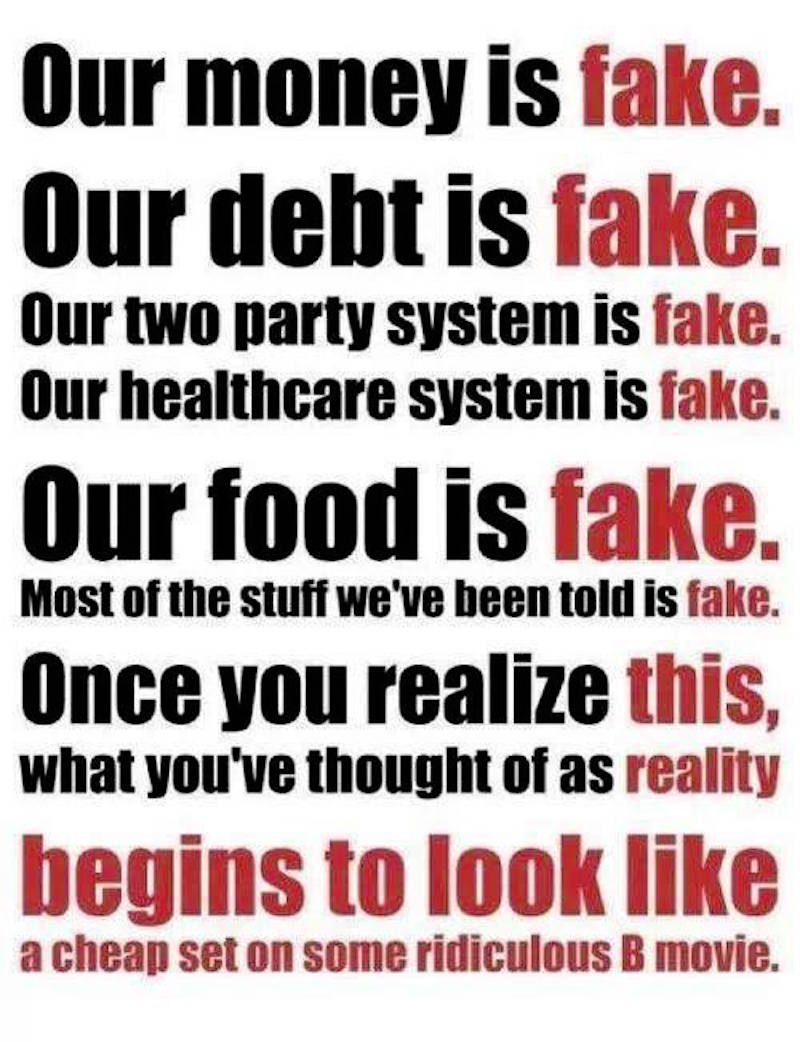

As you see, the US has quite a parasite load of bad political technologies. Each special interest group can hire some political technologists to put together a system for them that will assure them of a disproportionately large piece of the pie to the detriment of everyone else.

This is bad enough, but bad political technologies cause an additional problem: they debilitate the minds of those they afflict. Their main objective is to keep people convinced of things that are false. Once they succeed, these people become personally invested in these falsehoods, come to identify with them, and regard any information that contradicts them either as a personal affront or, at the very least, as a source of unwelcome cognitive dissonance. This makes them impervious to good political technologies—ones that seek to convince them of things that are true and of approaches that do in fact work, and steer them in the direction of doing what is necessary. They are what Andy Borowitz called "fact-resistant humans."

Comment: Most of these people could also be called what Bob Altmeyer describes as "authoritarian followers":

An authoritarian follower submits excessively to some authorities, aggresses in their name, and insists on everyone following their rules.

Because of its high parasite load of bad political technologies, the population of the US may not be worth the trouble when it comes to putting together good political technologies, such as the one to prevent catastrophic climate change. A lot of these bad political technologies are poised to fail, either through internal contradiction, or because of their deleterious effects on the people held in their spell, so it makes sense to wait.

Also, the problem of the US being a major polluter and climate disrupter may resolve itself: the US stands to suffer immensely from climate change, with the west coast and the southwest running out of water, the south decimated by heat waves and the eastern seaboard disappearing under the waves. Keep in mind that it amounts to less than 5 percent of the world's population—a significant number, but not significant enough to hold up the rest of the planet.

Trying to negotiate with the US when it comes to preventing catastrophic climate change is starting to seem like a waste of time. Why should the 95 percent wait for the 5 percent to dig a deep enough hole for themselves? But what wouldn't be a waste of time? This is the question we will take up next.

Part 3

Previously in this series of posts we outlined how inside the US special interests use political technologies to keep the population fooled. We also showed how these efforts will eventually fail, either through internal contradiction or because the parasites eventually end up killing the host. We will now turn our attention to political technologies used by the US against the rest of the world. This may seem like a digression from the task of addressing the question at hand—of how to bring about social change in order to avert climate catastrophe—but it is necessary.

The long list of political technologies used within the US to keep Americans fooled helped us show just how pervasive and destructive these technologies are. We are yet to see any ways to neutralize these technologies—because Americans have failed to do so. To find examples of successful ways to neutralize them, we have to look at what the US has been attempting to do to the rest of the world—and failing.

No matter how good America's luck has been—isolated geographic location, plentiful natural resources, the gigantic windfall of its victory in World War II, the additional windfall of the Soviet collapse—the luck was bound to run out eventually. In fact, to a large extent it already has: as a purely practical matter, it simply isn't possible to continue running roughshod over the entire planet if you run roughshod over your own population as well. The US has less than 5% of the world's population, half of whom are obese, a third on drugs and a quarter mentally ill. It leads the world in deaths from gun violence, police murders and prison population. Half the children are born into poverty and a third into broken and nonexistent families. Over a quarter of the working age population is permanently out of work. By no stretch of the imagination is this a description of a group that can rule the world..

Beyond the simple matter of all good (or, if you prefer, evil) things eventually coming to an end, the rest of the world has evolved some effective antibodies against American political technologies, and some of them may be helpful in bringing about the rapid social changes that are needed in order to avert climate catastrophe. Before the US empire is swept away in a wave of confusion and embarrassment, we may be able to extract some useful lessons from it.

We can divide the political technologies the US uses against the rest of the world into three broad categories. Although the first two may not involve overt, physical violence—at least not every time they are applied—all three categories are actually forms of warfare—hybrid warfare.

- International Loan Sharking

- The Orange Revolution Syndicate

- Terrorism by Proxy

Economic hit men (EHMs) are highly paid professionals who cheat countries around the globe out of trillions of dollars. They funnel money from the World Bank, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and other foreign "aid" organizations into the coffers of huge corporations and the pockets of a few wealthy families who control the planet's natural resources. Their tools included fraudulent financial reports, rigged elections, payoffs, extortion, sex and murder. They play a game as old as empire, but one that has taken on new and terrifying dimensions during this time of globalization.These efforts eventually produce a bankrupt country that is unable to service its foreign debt. Whereas in previous eras the US used gunboat diplomacy to extort payments from deadbeat countries, in a globalized economic environment this has been rendered largely unnecessary. Instead, the simple threat of refusing to provide liquidity to the country's banks is enough to make it capitulate. In turn, capitulation leads to the imposition of austerity: health, education, electricity, water and other public services are either cut or privatized and bought up on the cheap by foreign interests; private savings are confiscated to make symbolic payments against a ballooning foreign debt; subsidies and tariffs are changed to benefit G8 nations to the country's detriment, and so on. Society crumbles; young people, and anyone talented or educated, tries to emigrate, leaving behind the destitute old, the hopeless, and the social predators.

This political technology has worked a great deal of the time, most recently with Greece, Portugal and Ireland. But there are still some countries which, although integrated into the global economy, are politically able to withstand this juggernaut and insist on maintaining their sovereignty and on pursuing a set of policies independent from Washington's dictate. In these cases, the US deploys a different political technology, which goes under the name Orange Revolution (although the actual colors vary). This technology uses large groups of nonviolent protesters to produce social disorientation, disorganization and disintegration, to render the political elites within a country impotent, and to exploit the moment of chaos and confusion in order to install a puppet regime that can be controlled from Washington.

The methods of Orange Revolution are often touted as a nonviolent way to bring about regime change. Gene Sharp, the great theoretician of nonviolent revolution, is insistent that all protest should be nonviolent. But the concept nonviolence, comforting though it is to delicate minds, needs to be set aside—because it just plain doesn't exist.

Just because a crowd isn't throwing Molotov cocktails at police while illegally blocking access to a public building does not make it nonviolent. First, the use of a crowd for a specific purpose is already a form of force. Second, if the demonstration is illegal, and if restoring public order would require violence, then the crowd is using the threat of violence against itself as a weapon against the rule of law. Calling such a crowd nonviolent is tantamount to declaring that a man making demands while pointing a gun at his own head isn't being violent simply because he hasn't shot himself yet.

The architects of regime change insist on the use of "nonviolent" tactics specifically because they pose a much thornier problem for the authorities than an outright revolt. If the government faces an armed uprising, it knows exactly what to do: put it down. But when the youth of the nation parades around in matching T-shirts (that have been mysteriously shipped in from abroad) shouting deliberately anodyne, aspirational slogans, and the entire happening takes on the air of a festival, then the government's ability to maintain public order gradually melts away.

When the conditions are right, the regime changers fly in the mercenaries with the sniper rifles, carry out a public massacre, and blame it on the government. These snipers appeared in Egypt in 2011 during the effort to topple Hosni Mubarak. They also appeared in Vilnius in 1991 and in Moscow in 1993. In Tunisia in 2011 they actually got detained. They had Swedish passports and Northern European faces. They said that they were there to hunt wild boar—with sniper rifles, in Tunis.

Let us not allow ourselves to be misled: all three types of political technologies the US uses against the rest of the world are types of warfare—hybrid warfare—and "nonviolent warfare" is an oxymoron. "Nonviolence" is a misnomer; with respect to Orange Revolutions, the correct term is "delayed use of violence."

What transpires in the course of an Orange Revolution is typically as follows:

Phase 1: Groundwork. The action is instigated by a small, ideologically and politically unified, networked group of elite individuals sponsored by Washington's NGOs, think tanks and the US State Department. Their goal is to appear to the government as "the voice of the people" and to the people as "the legitimate authorities." They use methods of information warfare: hunger strikes, small demonstrations, speeches by dissidents and symbolic clashes with police in which the protesters play the victim. To hide the fact that they are a small, closed clique of outsiders and foreigners in Washington's pay that has conspired to overthrow the government, they merge into large popular groups of citizens, infiltrate legitimate protest movements, and inject their specific slogans alongside popular public demands. Once they achieve a "virtual majority" and accumulate enough followers to march them out for a photo shoot so that Western media outlets can champion them as a popular protest movement, they move on to...

Phase 2: Destruction of Public Order. During this phase, the goal is to achieve maximum social disruption through nonviolent means. Streets and public squares are occupied by almost perfectly peaceful crowds of young people chanting moderate, popular slogans. They start by holding officially sanctioned demonstrations, then start probing the limits by changing the route or by holding meetings longer than scheduled. They start using ploys such a sit-down demonstration accompanied by the announcement of an indefinite hunger strike. While doing this, they actively propagandize the riot police, demanding that they be "one with the people" and trying to force them to become complicit in their at first minor transgressions against public order. As this process runs its course, public order gradually disintegrates.

During this phase, it is important that the protesters do not engage in any sort of meaningful political dialogue, because such dialogue may lead to a national consensus on important issues, which the government could then champion, restoring its legitimacy in the eyes of the people while sapping the protest movement of its power. The regime changers pursue the opposite strategy: of delegitimizing the government by proliferating all sorts of councils and committees that are then held up as democratic, and therefore legitimate, alternatives to the government.

The time of elections is a particularly opportune moment for the regime changers to exploit by claiming that there has been fraud at the polls and by using the social organizations they have infiltrated as fronts in order to claim to be speaking on behalf of the true majority. The White Ribbon Revolution in Bolotnaya ("Swamp") Square in Moscow on May 6, 2012, right before Putin was to be reinaugurated as president, went nowhere; in that instance, the regime changers broke their teeth, and their local operatives in the "opposition movement" are now some of the most widely despised people in Russia. (Hilariously, the little white ribbons, which were shipped into Russia from somewhere just in time for this action, had also been worn by Nazi collaborators during World War II—something many Russians knew while the foreign puppetmasters behind the fake protests clearly didn't.) But almost the same technology did work later during the Euromaidan Revolution in Kiev in February of 2014.

When those tasked with protecting what's left of public order become sufficiently worn down to react forcefully when the situation calls for it, the stage is set for...

Phase 3: The Occupation. During this phase, which, if effective, is quite short, the protesters storm and occupy a symbolically important public building. This is a very traditional revolutionary tactic, going back to the storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789, or the storming of the Winter Palace on November 7, 1917. If the preparations were successful, by this point the government is too internally conflicted to act, the defenders of public order are too demoralized to follow their orders, or both. In some cases, as in Serbia, in Georgia and in Kyrgyzstan, this is all it took to move on to phase 5. The highly organized people behind the supposedly spontaneous blitz now declare themselves as the legitimate government, and demand that the real government obey them and step down. However, sometimes it doesn't work, in which case there is always...

Phase 4: The Massacre. Mercenaries with sniper rifles are flown in and ushered into the upper floors of public buildings overlooking city squares where rallies and demonstrations are being held. By this time the defenders of public order are sufficiently demoralized by their inaction in the face of increasingly brazen challenges from the protesters that a few of them can be easily corrupted by large bribes from the foreign sponsors of the regime change operation. They accept the money and depart from the scene, leaving doors unlocked or even handing over the keys. The mercenaries go to work and kill a hundred or so people. Western media immediately express outrage, pinning the responsibility for the massacre on the government, and demanding that it resign. The protesters are incited to immediately echo these slogans and a groundswell of misplaced outrage sweeps the government out of power, setting the stage for...

Phase 5: Regime Change. The new government, hand-picked by the US embassy and the US State Department, assumes power, and is immediately given recognition and support by Washington.

This strategy can be quite successful—to a point. As we shall see, society can and sometimes does develop effective antibodies against it. It is notable that just about any government—from the most democratic to the most autocratic—is susceptible to it, the only real exceptions being absolute monarchs who can make heads roll the moment someone starts speaking out of turn, or those rulers who derive their legitimacy from a divine right that cannot be questioned without committing sacrilege.

The government has no good tactical options. It cannot declare the mass of protesters outside the law, because they are, after all, its citizens, and most of them are not even directly guilty of any administrative transgressions. But if it is to restore public order, it must crack down on the demonstrators. If it cracks down early, then it looks heavy-handed and authoritarian, handing ammunition to the protest movement. If it cracks down at the height of the protests, then it causes a lot of unnecessary casualties, turning much of the population against itself. And if it attempts to crack down when it's too late, then it only ends up looking even weaker, accelerating its own demise.

But the government does have an excellent strategic option, provided it lays the groundwork for it beforehand. The problem with opposing this sort of supposedly nonviolent, externally driven regime change operation is that it cannot be effectively opposed by a government. But it can be quite effectively opposed and disrupted by a relatively small group of empowered individuals acting directly and autonomously on behalf of the people. This is the topic we will take up next.

We will not discuss the third method of regime change—Terrorism by Proxy—because, frankly, it doesn't work. It is yet to result in the installation of a stable puppet regime in any of the countries where it has been tried. It failed in Afghanistan: after the Soviets finally withdraw, the country became a failed state. America's pet terrorists, termed al Qaeda, were then used as decoys to justify invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, but the decoys came to life and threatened to destabilize the region. The latest group of America's pet terrorists, ISIS, who, as of this writing, are so impressed by the Russian bombing campaign against them that they are busy shaving off their beards and running away, has become a huge embarrassment for the US. Terrorism by Proxy does reliably produce failed states, and although some may claim that this is a reasonable foreign policy end-goal, it is very hard to argue that it is in any sense optimal.

In a sense, this is a requiem for these three political technologies.

The first one—International Loan Sharking—is not going to work too well going forward. Developing countries can now borrow from China's Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, in which they can become shareholders. Countries around the world are unloading their dollar reserves and entering into bilateral trade arrangements that circumvent the dollar system. With its own finances in disarray, the US is no longer able to function as the purveyor of financial stability.

The Orange Revolutions have also largely run their course, because the political technology for neutralizing them is by now quite far along. The latest large-scale effort—in the Ukraine in 2014—has resulted in a failed state. Subsequent efforts in Hong Kong and in Armenia fizzled.

Lastly, Terrorism by Proxy not only never worked correctly, but is now poised to prove hugely embarrassing for the Washington establishment. The Russians, with Syrian, Iranian and Iraqi help, are swiftly rubbing out America's pet terrorists with equanimity and poise, while their erstwhile puppetmasters in Washington are visibly demoralized and spouting preposterous nonsense. But there are still some important lessons to be extracted from all this—and we should extract them before it all gets covered by a thick layer of dust.

Reader Comments

Do more than laugh at (or cringe at the cosmic stupidity or shake in terror at the invariably demonic nature of) fools.

Make sure that you are not one of them.

Putin is not the anti Obama, though he may have some good qualities. He may in fact be the anti Obama Obama.

The following article is really good, but be sure to understand it in its depth:

[Link]

DO NOT BE FOOLED AGAIN.

AND AGAIN.

AND AGAIN.

I would appreciate it.

ned, out

. . . here's a snip worth its weight from the article ned linked to:

"“Firearm possession should be banned in America; president Obama can orchestrate this directive,” insists LeSavoy – who somehow obtained a doctorate degree without learning even the rudiments of constitutional law. (Perhaps she is more familiar with the Soviet version, circa 1938.) Her prose likewise suggests that she enjoyed the dubious benefit of very uncritical English teachers."

Although the whole text does rather belabour the obvious, it was an enjoyable respite from the endlessly passing sh*t show.

Every political leader, everywhere, at all times, should be looked at with mistrust and suspicion. Every plan they make, should be folded, spindled and mutilated.

We are in deep shit because of them.

Take it from there.

I personally doubt there are any good ones.

If you're going to help someone, help them directly, with your own hands and heart.

ANARCHY.

ned

Usually transliterated as prepodobny is actually a very ancient word though it may only have been ecently used in this kind of context. In a religious context it actually means something like "according to the original nature" --or the prefallen likeness of God in human nature. It is traditionally used to describe those saints who attain to traits of the prefallen humans in paradise--such as harmony with nature and with wild animals. Feeding bears out of the hand etc. Which is common in Orthodox saints historically and up to the present. It is most commonly used instead of the the word for saint (svyati) when applied to a monastic saint--where it means most clearly --according to the likeness. You can't actually dismiss this older content of the word in this context because I am sure that Putin does not.

[Link]