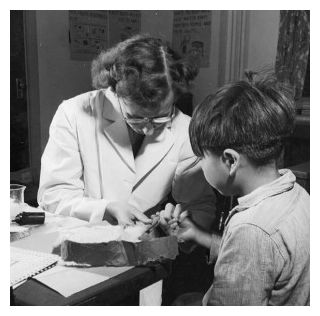

In the 1940s, the children were also, as more and more evidence is revealing, the unwitting subjects of bizarre, cruel and unethical experimentation.

A recently uncovered experiment reveals the depths of the access given to so-called researchers seeking to find evidence that aboriginal children, by dint of their race, had extrasensory perception, also known as ESP, or a "sixth sense."

Fifty children at the Indian Residential School in Brandon, Manitoba, became the subjects of a series of tests that sought to establish a new measure for identifying ESP and also to find evidence of supernatural abilities of "primitive" people.

The study was conducted for researchers at what was then known as the Duke Parapsychology Laboratory; the findings were published in the Journal of Parapsychology in 1943.

"The bare fact that American Indians have shown ESP ability is not surprising enough to deserve great emphasis," the study's author wrote.

The study was recently uncovered by Maeengan Linklater, an aboriginal community worker, who forwarded it to Ian Mosby, a researcher at McMaster University.

Duke University has since cut ties with the laboratory, which continues its work under a new name: the Rhine Research Center.

ESP and human behavioral phenomenon that "transcend the known physical laws of nature" were once hot topics of scientific interest, but have fallen from favor.

"It's fallen into disuse due to the fact that there's just nothing there," Scientific American columnist Michael Shermer told Discovery.com. "Parapsychology has been around for more than a century. (Yet) there's no research protocol that generates useful working hypotheses for other labs to test and develop into a model, and eventually a paradigm that becomes a field. It just isn't there."

The aboriginal children in Canada were tested based on their ability to guess what was written on a card that was being looked at by the researcher - essentially reading someone's mind. But the results were inconclusive: The children's performance was no better than chance.

The "research" experiment highlights just one of the many indignities suffered by these children, according to Mosby, a postdoctoral fellow in Canadian history at McMaster.

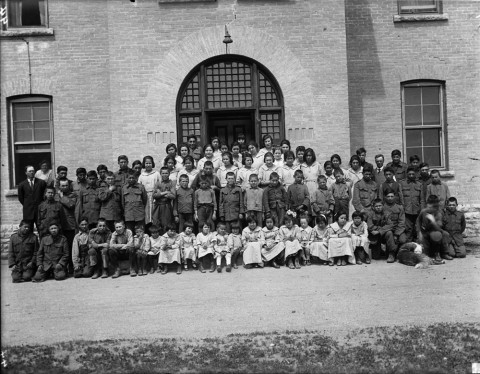

The children, the old study notes, came from "primitive" cultures where fishing, hunting and trapping were the primary occupations. They were brought to the schools as young children and kept there, away from their families, for most of the time.

More than 150,000 aboriginal children were forced to attend these schools until the last one was closed 1996. They were run by churches but funded by the government.

Meals at the schools consisted of oatmeal gruel and toast for breakfast followed by thin soup for lunch and dinner, even while school administrators ate rich foods prepared by the students themselves. Hunger and malnutrition were common, and many of the children died there - in some cases, death rates exceeded 50 percent of the students.

In 2013, Mosby published a paper describing nearly a decade of "nutritional" experimentation conducted on aboriginal children. The experiments involved depriving children of nutrition in the name of science and allowing conditions of virtual starvation to continue.

"The mortality rates of these schools were vastly higher than the rest of Canada," Mosby said. "This comes back to the dehumanizing elements of residential schools in Canada. The entire purpose of them was to destroy indigenous ways of life."

Linklater, who unearthed the study, forwarded it to Mosby because the researcher had previously examined other experiments conducted on aboriginal children during that time period.

"There's no parental consent, there's no research studies that would have been ethical by our standards today, and these kids were exploited," Linklater told the Canadian Broadcasting Corp. "I don't mean to say this to inspire white guilt, I'm using this as a tool for change."

In 2008, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper formally apologized to the aboriginal community for the schools and the country settled a class-action lawsuit brought by surviving former students.

"The really important point is it highlights the vulnerability of indigenous children in Canada and the lack of care," Mosby said. "The idea that they would let quack scientists do experiments on children highlights the inhumanity of these institutions."

No harm my eye, you destroy them inside and out and blame them for their ability not to conform.

Harper...we cant impeach the bastard, but we can vote with a bullet...useless dandy...may a meteorite strike his house while he sleeps on the bed 'we' bought for him.