A mysterious cluster of severe birth defects in rural Washington state is confounding health experts, who say they can find no cause, even as reports of new cases continue to climb.

Federal and state officials won't say how many women in a three-county area near Yakima, Wash., have had babies with anencephaly, a heart-breaking condition in which they're born missing parts of the brain or skull. And they admit they haven't interviewed any of the women in question, or told the mothers there's a potentially widespread problem.

But as of January 2013, officials with the Washington state health department and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had counted nearly two dozen cases in three years, a rate four times the national average.

Since then, one local genetic counselor, Susie Ball of the Central Washington Genetics Program at Yakima Valley Memorial Hospital, says she has reported "eight or nine" additional cases of anencephaly and spina bifida, another birth defect in which the neural tube, which forms the brain and spine, fails to close properly.

"It does strike me as a lot," says Ball.

And at least one Yakima mother whose baby is part of the cluster says no one told her there was a problem at all.

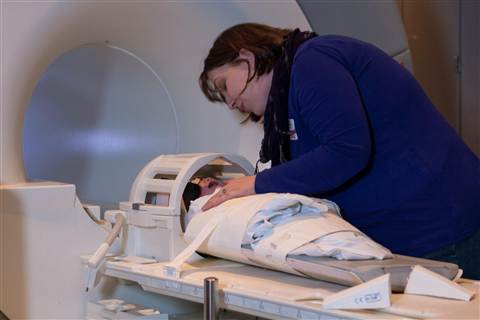

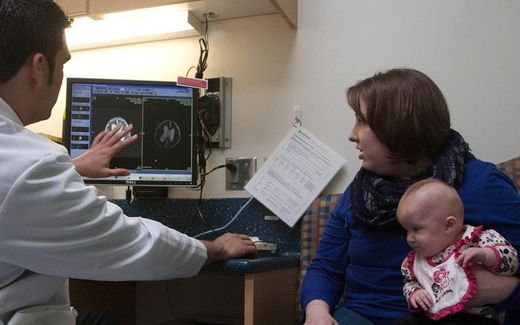

"I had no idea," said Andrea Jackman, 30, whose blue-eyed daughter, Olivia, was born in September with the most severe form of spina bifida. "I honestly was really surprised that nobody had said anything. If my doctor hadn't wanted us to see the geneticist, I wouldn't have known."

The agencies released a report last summer detailing an investigation of 27 women with pregnancies that resulted in neural tube defects in Yakima, Franklin and Benton counties between 2010 and 2013. That included 23 cases of anencephaly, a rate of 8.4 per 10,000 live births, far higher than the national rate of 2.1 cases per 10,000. There were three cases of spina bifida and one with encephalocele, a sac-like protrusion of the brain through the front or back of the skull.

They publicly posted the results of the investigation in press releases and on state and federal websites. Those were picked up in news stories, including one in the local newspaper, the Yakima Herald-Republic. "State says no cause found for birth defect in Yakima County," the July headline read.

But it's not clear whether affected women saw those stories, and there was no effort to reach out to individual families, said Mandy Stahre, the CDC's Epidemic Intelligence Service Officer based in Washington state, who led the inquiry. "There were very few of us that could spend time doing this investigation," Stahre said. "I'm not sure the women knew they were part of a cluster."

Health officials originally were alerted to the problem by a nurse, Sara Barron, 58, who was in charge of infection control and quality assurance at Prosser Memorial Hospital, a 25-bed medical center in the farm town set on the Yakima River. A 30-year nursing veteran, she'd seen perhaps one or two devastating cases of anencephaly in her wide-ranging career.

"And now I was sitting at Prosser, with 30 deliveries a month and there's two cases in a six-month period," Barron said. "Then, I was talking to another doctor about it and she has a third one coming. My teeth dropped. It was like, 'Oh my God.'"

At a regional medical meeting, there were more anecdotal reports. So Barron notified state health officials, who started looking into the problem.

"This is bizarre," Barron said. "This is a very, very small area."

Investigators pored over medical records of the 27 area women with affected pregnancies and 108 matched controls who received care at the same 13 prenatal clinics, Stahre said. They examined where the women worked, what diseases they had, whether they smoked or drank alcohol, what kind of medications they took and other factors. They looked at where they lived and whether they got their water from a public source or a private well. They looked at race and whether the problem was more pronounced in the area's migrant farm workers or in other residents.

In the end, there was nothing - "no common exposures, conditions or causes," state officials said - to explain the spike.

"No statistically significant differences were identified between cases and controls, and a clear cause of the elevated prevalence of anencephaly was not determined," the CDC wrote.

The results were disappointing, but not entirely unexpected, said Jim Kucik, a health scientist with the CDC's Birth Defects Surveillance Team who reviewed the results. There's not usually one single factor that causes such birth defects and it can take an examination of a much larger population to find when something's wrong.

"This cluster is fairly small in size. It makes it challenging to find that smoking gun," he said.

A group of birth defects can appear to be related, when it's actually just coincidence, Kucik added. "I think that there is a lot of frustration when dealing with these type of cluster investigations because they end up without a lot of answers," he added.

Adding to the problem is that investigations take time and personnel. Stahre and her crew relied only on medical records for their study because there weren't resources for a full "boots-on-the-ground" effort, Kucik explained.

"We certainly don't shrug off any indication of high rates of birth defects," he said.

But that doesn't help Andrea Jackman, who was an assistant manager at a Yakima Blockbuster Video store when she discovered she was pregnant - and then that the baby had spina bifida.

"The doctor who did the ultrasound said she'd be in a wheelchair the rest of her life. He pretty much told us she'd be a vegetable," said Jackman, who now lives with Olivia at the home of her aunt and uncle in Ellensburg, Wash.

The news was devastating, and Jackman initially considered ending the pregnancy.

"Then I decided that it wasn't my decision to make," she said. "If she wasn't going to live, it wasn't going to be my decision."

"It was scary at first, but every time they see her, she gets better and better," Jackman said.

Olivia's defect isn't as severe as some, but she's still considered part of the cluster of neural tube defects in the region. Jackman said that if she'd known that other area women had babies with similar birth defects, she would at least have been aware that the issue existed.

That concern is shared by experts in neural tube defects, who say health officials should look harder - and spread the word about what what they find.

"Any time you see a geographic cluster of a pretty severe birth defect, it does make you wonder if there is a common exposure contributing," said Allison Ashley-Koch, a professor at the Duke University Medical Center for Human Genetics, whose focus is anencephaly. "If there were resources, it really would be wonderful to go back to the families to conduct more intensive interviews regarding common environmental exposures."

That's been true in high-profile clusters, including one in Texas in April 1991, in which three babies with anencephaly were born in a Brownsville hospital within 36 hours. It sparked years of surveillance and research that found that the problem could be traced in part to the lack of folic acid in the diets of the mostly Hispanic women who lived on the Texas-Mexico border. Obesity and diabetes appeared to be factors, as did exposure to fumonisins, or grain molds.

Research has shown that there are potential links between anencephaly and exposure to molds and to pesticides, Ashley-Koch said. Central Washington is a prime agricultural area that produces crops from apples and cherries to potatoes and wheat, which may require pesticides that contain nitrates.

"They may have eaten the same type of produce from a particular grower or farmer, which essentially put all those folks at risk," she said.

A Texas A&M University Health Science Center study published last year found that mothers of babies with spina bifida were twice as likely to ingest at least 5 milligrams of nitrate daily from drinking water than control mothers of babies without major birth defects.

The study, led by Jean Brender, associate dean of research at the School of Rural Public Health, found that nitrate levels in drinking water varied widely according to the source, with average levels of 0.33 miligrams per liter in bottled water, 5.0 milligrams per liter in public water supplies and 17.5 milligrams per liter in private wells.

"I have a daughter in her childbearing years," Brender said. "If she were on a private well, I would tell her to have her well-water tested or drink bottled water."

Ashley-Koch, the Duke professor, acknowledged that CDC and state officials faced a tough task. It's difficult tracing back through previous pregnancies and trying to find a common cause for birth defects, particularly when not all of defects are the same. Still, she suggested that the investigation may have been a "cursory approach."

"Without actually conducting interviews, it's pretty difficult to discern what potential exposures may or may not have occurred," she said.

Sara Barron, the nurse who discovered the problem, thinks that health officials could - and should - do more.

"I definitely believe something is going on," she said. "There was something. Maybe it just hit once and blew through, God willing. If there are still cases going on, we need to know."

CDC and state officials refused to tell NBC News how many new cases they'd received in 2013, saying they plan a full report later this spring. Stahre had previously said they'd received "a few more cases" after the original investigation.

Susie Ball, the genetic counselor who has reported additional cases, said she's "not convinced - yet" that there's a problem in the area and that it may take more time to tell. She wouldn't want to scare people, she said. Still, she said the situation should be more widely publicized to let local women of child-bearing age know the risk - and to help them take action to prevent birth defects.

"Make sure that everyone who could become pregnant knows they should be taking folic acid," Ball said, referring to the B vitamin that can help prevent spina bifida. "Look at this unexplained spike here in the valley. Take your folic acid."

It's the lack of information that still haunts Andrea Jackman, who said she lived near a pesticide-laden apple orchard and drank well water in the couple years before her surprise pregnancy.

"There's got to be something. I mean, something causes it," she said. "Every mother wants their child to be perfect. If you could find a way to stop this from happening, why wouldn't you want to do that? Why would you not want to tell people?"

"There's no secret, state and CDC officials said, and they noted that small clusters of birth defects often turn out to be nothing more than sad coincidence."

No. Clusters of similar birth defects outside of the average aren't a "coincidence". They're being caused by something. Maybe the cause will never be found, but don't use your authority to try to encourage parents not to investigate. Just because you've failed in the past to identify what is causing the defects in similar small clusters, doesn't mean that it doesn't exist, IT MEANS YOU FAILED.