The Chelyabinsk Meteor

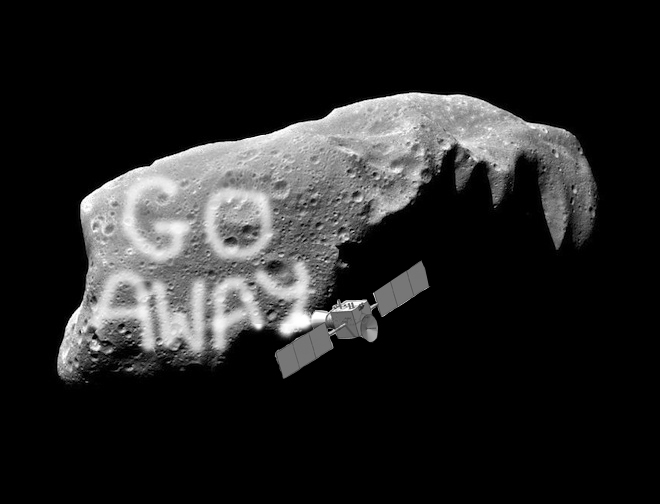

In February, a meteor struck the Earth's atmosphere and exploded above Chelyabinsk, Russia, causing more than 1,000 injuries but no deaths. Had it approached at a slightly different angle, the carnage would have been titanic. The explosion should have served as a warning. Instead, the story flashed briefly across the world's consciousness, then vanished. The dissipating of interest is easy to understand: A meteor strike in which nobody dies is "dog bites man," not "man bites dog."

But we should be paying closer attention. In November, the journal Nature published two papers that concluded that impacts of similar meteorites are more frequent than previously thought, and they could do enormous damage should the kinetic energy not be absorbed in the atmosphere. The Chelyabinsk meteorite, as it turns out, had a diameter of only about 20 meters (about 66 feet) but caused damage 90 kilometers (60 miles) away. It weighed at least 12,000 metric tons, far heavier than initially thought. It exploded with the energy of a 500-kiloton nuclear blast (by way of comparison, the bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki had yields of 15 and 20 kilotons, respectively). So a ground burst would have been a disaster.

Historically, the atmosphere has protected the surface of the Earth from collisions with relatively small asteroids. But there are plenty out there measuring 50 meters (almost 165 feet) in diameter and more, the size known to astronomers as "city killers." An extraterrestrial object of that size would likely survive contact with the atmosphere and produce a devastating ground burst. The University of Hawaii's Asteroid Terrestrial-Impact Last Alert System, funded by a grant from NASA, is designed to give one week's warning of the impact of asteroids of city-killer size -- or larger. It is expected to be in place by the end of 2015.

If, as researchers believe, a city killer arrives about once a century, then we are due: The last one struck Siberia in June 1908. We're not close to ready. There are a number of truly imaginative plans out there, including one that involves white paint. Yet NASA lacks the money for a serious response system, even though it is under congressional mandate to have one by 2020.

No doubt there will be endless appropriations (and recriminations) once a city killer actually strikes. "Any fool can tell a crisis when it arrives," wrote Isaac Asimov. "The real service to the state is to detect it in embryo."

Pope Francis' Encyclical

Pope Francis has captured the imagination of the world, even if his messages have been widely misunderstood. Even Time magazine, which named Francis its person of the year, had to correct its erroneous assertion that he had rejected church dogma. If we hope to understand Francis, we might begin not by celebrating his carefully nuanced statements on issues around which our politics revolve, but by studying his considered words about the Christian faith itself. I would suggest an examination of the only encyclical he has issued so far, Lumen Fidei ("Light of Faith"). There Francis has this to say: "Love and truth are inseparable. Without love, truth becomes cold, impersonal and oppressive for people's day-to-day lives."

In the midst of the holiday season, these words ought to resonate. Francis, of course, is speaking of the light of Christ, but one needn't be Christian, or even religious, to see the broader point. All of us have a terrible tendency toward unwarranted certainty -- certain we are right, certain others are wrong, certain that if our ideas were only adopted all would be sweetness and light to the end of time.

When we find the truth, we often decide that what really matters is that everybody else honor the truth that we have discovered. And when we discover that others don't honor our truths -- that they have truths of their own -- we turn against them in confusion and even horror.

This isn't the place to catalog the woeful character of our political debate. But the mentality against which Francis warns does not manifest itself only in the meanness that we ascribe to our opponents. Too often it characterizes the very design of policy. We tend to work at high levels of abstraction, dealing with people as statistical masses rather than as individuals with their own interests and desires and -- most important -- their own dignity.

Our seeming inability to look with love upon those who differ leads to a profound alienation from both politics and policy. I suspect that it lies behind the movement in Silicon Valley toward searching for a place to found an alternative country, one less regulated, in which there is a greater freedom to experiment, not just technologically but in other ways as well -- "to peacefully opt out," in the words of Stanford University lecturer Balaji Srinivasan.

Even if we followed Francis' advice and tempered truth with love, there would still be many dissatisfied with government policy. But I would like to believe that such a change would help make our politics less alienating, and our government more respectful.

That belief, I suppose, is itself an act of faith. If so, this is the right season for it.

(Stephen L. Carter is a Bloomberg View columnist and a professor of law at Yale University. He is the author of "The Violence of Peace: America's Wars in the Age of Obama" and the novel "The Impeachment of Abraham Lincoln." Follow him on Twitter at @StepCarter.)

Comment: For a historical perspective on Comets and human society, please read Laura Knight-Jadczyk's 'Comets and the Horns of Moses (The Secret History of the World)'

I and others have seen the big one.

Art work offered (again) to SOTT.

This is not a joke.

It will come back again.

You profess belief in these things but shun the evidence of a well qualified observer. An observer who really does not want to see it and reports it only out of a sense of resposibility.

Perhaps you prefer the matrix?