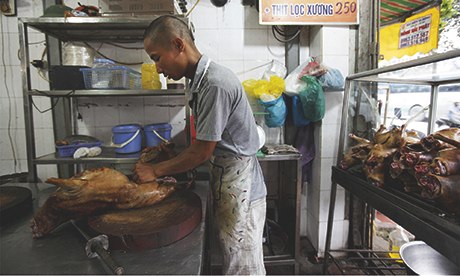

Nguyen Tien Tung is just the sort of man you'd expect to run a Hanoi slaughterhouse: wiry, frenetic and filthy, his white T-shirt collaged with bloodstains, his jean shorts loose around taut, scratched-up legs, his feet squelching in plastic sandals. Hunched over his metal stall, between two hanging carcasses and an oversized tobacco pipe, the 42-year-old is surveying his killing station - an open-air concrete patio leading on to a busy road lined with industrial supply shops.

Two skinless carcasses, glistening pure white in the hot morning sun, are being rinsed down by one of Nguyen's cousins. Just two steps away are holding pens containing five dogs each, all roughly the same size, some still sporting collars. Nguyen reaches into one cage and caresses the dog closest to the door. As it starts wagging its tail, he grabs a heavy metal pipe, hits the dog across the head, then, laughing loudly, slams the cage door closed.

Down the leafy streets of north Hanoi's Cau Giay district, not far from Nguyen's family business, sits one of the city's most famous restaurants, Quan Thit Cho Chieu Hoa, which has only one thing on the menu. There's dog stew, served warm in a soup of blood; barbecued dog with lemongrass and ginger; steamed dog with shrimp-paste sauce; dog entrails sliced thin like sausage; and skewered dog, marinated in chilli and coriander. This is just one of a number of dogmeat restaurants in Cau Giay, but it is arguably the most revered, offering traditional dishes in a quiet setting along a canal.

"I know it seems weird for me to eat here when I have my own dogs at home and would never consider eating them," says Duc Cuong, a 29-year-old doctor, as he wraps a sliver of entrails in a basil leaf and takes a bite. "But I don't mind eating other people's dogs." He swallows and clears his throat. "Dog tastes good and it's good for you."

No one knows exactly when the Vietnamese started eating dog, but its consumption - primarily in the north - underlines a long tradition. And it is increasingly popular: activists claim up to 5 million of the animals are now eaten every year. Dog is the go-to dish for drinking parties, family reunions and special occasions. It is said to increase a man's virility, warm the blood on cold winter nights and help provide medicinal cures, and is considered a widely available, protein-rich, healthy alternative to the pork, chicken and beef that the Vietnamese consume every day.

Some diners believe the more an animal suffers before it dies, the tastier its meat, which may explain the brutal way dogs are killed in Vietnam - usually by being bludgeoned to death with a heavy metal pipe (this can take 10 to 12 blows), having their throats slit, being stabbed in the chest with a large knife, or being burned alive. "I've got footage of dogs being force-fed when they get to Vietnam, a bit like foie gras," says John Dalley, a lanky British retiree who heads the Thailand-based Soi Dog Foundation, which works to stop the dogmeat trade in south-east Asia. "They shove a tube into their stomach and pump solid rice and water in them to increase their weight for sale." Nguyen has a simpler method for bumping profits: "When we want to increase the weight, we just put a stone in the dog's mouth." He shrugs, before opening up his cage for another kill.

The government estimates that there are 10 million dogs in Vietnam, where dogmeat is more expensive than pork and can be sold for up to £30 a dish in high-end restaurants. Ever-increasing demand has forced suppliers to look beyond the villages where dogs have traditionally been farmed and out to towns and cities all over Vietnam. Dog-snatching - of strays and pets - is so common now that thieves are increasingly beaten, sometimes to death, by enraged citizens. Demand has also spread beyond the country, sparking a multimillion-pound trade that sees 300,000 dogs packed every year into tight metal cages in Thailand, floated across the Mekong to Laos, then shuttled for hundreds of miles through porous jungle borders, without food or water, before being killed in Vietnamese slaughterhouses.

This is a black-market industry, managed by an international mafia and facilitated by corrupt officials, so it is little wonder activists have struggled to curb it. "At first it was just a handful of small traders wanting to make a small profit," says Roger Lohanan of the Bangkok-based Thai Animal Guardians Association, which has been investigating the dogmeat trade since 1995. "But now this business has become a fundamental export. The trade is tax-free and the profit 300-500%, so everybody wants a piece of the cake."

Tha Rae is a sleepy little town in Thailand's paddy-filled north-eastern state of Sakon Nakhon. But Butcher Village, as it is known, earned its name trading dogs 150 years ago, when a group of Vietnamese Catholics fled persecution at home. Today, locals say at least 5,000 people - one-third of the population - supplement their meagre farming incomes by snatching, selling or killing dogs for local and foreign consumption. It's a profitable hobby that can fetch up to £6 a mutt.

Transporting dogs without proper vaccination papers is illegal in Thailand, as is smuggling them into Laos without customs and tax documents. Eating them is not illegal, but it is not popular with locals, most of whom strongly oppose it. Yet here in Tha Rae, roadside stalls close to the town's main government building proffer sesame-cured, maroon-coloured slabs of sinewy dogmeat at 300 baht (£6) a kilo. Inside the large blue coolers that separate the stalls are the pale white carcasses of frozen dog parts: heads, torsos, haunches. "People use the heads and legs in tom yum soup," explains a stallkeeper, nursing her baby, "but you could make any kind of dish you want with it."

Despite the large numbers of dogs they smuggle out of the country every year, only a handful of people run the Thai operation, claims Edwin Wiek, cofounder of the Animal Activist Alliance, a Thai-based charity pushing to stop the trade. "We know these people: we know where they live, we know their names, we even have photographs," says Wiek, whose alliance relies on full-time informants in Thailand and Laos. "Some of the photographs show their cars - their numberplates could be easily traced - but they get away with it because they pay a lot of money [in bribes]. And as long as they keep paying, there will be people in the system who accept it and turn a blind eye."

Activists claim that one such person is the mayor of Tha Rae, Saithong Lalun, who lives in a newly built mansion with colonnaded balconies and is said to profit directly from the industry. While he declined to be interviewed, citing past media interviews as causing the "suffering" of his constituents, a disgruntled politician who works closely with him will speak on condition of anonymity. "Of course the mayor knows the trade is going on: he's involved in it," he says. "The police and governor of Sakon Nakhon also have the capacity to end the trade, but they haven't."

Crackdowns have increased, however, thanks to a large network of informants working primarily with the Royal Thai Navy, which intercepted a shipment of nearly 2,000 dogs in April and another 3,000 in May, as they were being stacked on to boats and shipped to Laos. Leading the busts was Captain Surasak Suwanakesa, 45, naval commander of the regional Mekong Riverine Patrol Unit, who oversees 253km of the Thai-Laos river border crossing. His desire is to end the dogmeat trade once and for all. "It really is a point of shame for this country," he says, shaking his head.

But Surasak, who has been in this post for only nine months, has much larger and more pressing illegal substances to contend with on his waterways, such as yaba (crystal meth), cannabis and rosewood. On his iPad, he runs through images of previous raids, in which naval officers pose in front of their "bounty", then outlines a map to highlight the dog smugglers' route. "There are two major strategic crossings," he says. "The dogs are collected from village households, or stolen, sold for 200 baht [£4] each, then sent to Tha Rae. From there, the bigger dogs are sent to a northern district, Baan Pheng, to go to China, while the smaller ones go to Vietnam. Five minutes across the river and the price of the dogs can go up 10 times. That's why the incentive is so high."

The naval team depends on tipoffs from locals to crack down on the trade, but arrests are few and far between, activists say, with most smugglers paying only small fines and going back into business within days. Those orchestrating the deals are never pursued, and the men truly at risk are those trying to stop the trade: in an industry that Wiek claims could earn the Thai mafia more than £1.25m every year, people such as Surasak are costing the smugglers a big drop in profit. "The commander before me had a price of 4m baht [£80,000] on his head. I don't know what mine is." He smiles. "The thing is, they're the same people, in the same cars, who do this again and again. When I catch them, I get them on as many counts of the law as I can: customs tax, vaccination and transportation permits, and so on. This is unusual. It hasn't been done before. Normally every relevant government office would get 1m baht [£20,000, in bribes]. It's a good thing this job is only three years long: you can make millions on this border if you want to."

The route the smugglers take to reach Vietnam is Highway 8, a two-lane ribbon of road that cuts through Laos's limestone mountain passes, past wooden shacks and the large, modern mansions of the wealthy elite. While still in Thailand, the dogs will have been crammed into poultry carriers or heavy metal cages, 12 to 15 dogs in each, six to eight cages per truck, every convoy worth around 160,000 baht (£3,200). They are driven, at night, to the border, before being floated across the Mekong and loaded on to other trucks. Using informants, fake numberplates and GPS to ensure their routes are clear and their cargo protected, the smugglers face nothing but open road from here on. "Once they hit Laos, there's no stopping them," one Thai informant says with a sigh. "They're home free."

The smugglers, if they stop for a break, generally do so in Lak Sao, the last city in Laos before the Vietnamese border. "You hear the trucks before you see them," the locals joke, as the convoys stream along these dusty roads almost every night, the howls of their cargo echoing through the cool mountain air. Following the route by public bus, I spot a lone dog truck travelling with empty cages on its way back to the Thai border.

"My friend's uncle helps load the dogs on to the trucks sometimes when he's not working in the rice field," says the student sitting next to me, who has just begun to describe the tradition of eating dogmeat in Laos when our bus stops in front of a cafe. Inside, two policemen are bundling a dog into an empty rice sack, which they twist quickly, then tie shut with a rope. The bag shakes violently as the dog squirms, trying to get out. "Maybe they're having a party tonight," the student says, as we watch the officers sit down at a table, light up cigarettes and go back to drinking coffee.

The Vietnamese border crossing is a remote mountain post manned by officers who ask for dollars in exchange for a passport stamp. It would be easy to get anything through here, it seems: the road is full of logging trucks carrying what looks like protected rosewood, and the officials who aren't asleep are openly demanding bribes. The road continues down towards the central city of Vinh, past French colonial schools and new houses with fairytale turrets. The number of dog-laden trucks passing through is endless, says Zuong Nguyen, 38, a wild-eyed bus driver who makes the six-hour journey from Vinh to Hanoi every other night. "Those trucks, they always have dogs, but lately I've seen cats, too."

In Hanoi, dog restaurants generally huddle together, with signs bearing a dog's head, or a roasted dog's torso hanging from a large metal hook. Along Tam Trinh, a stretch of road south of the city, dozens of roadside stalls sell roasted dog to customers arriving by motorbike and on foot, with lines sometimes 10 deep. Teenagers in basketball shorts chop up the dogmeat with heavy butchers' knives, sprinkling on a potent seasoning of curry powder, chilli, coriander, dill and shrimp paste, before skewering the meat to be barbecued. In the shop run by Hoa Mo - a 63-year-old woman who has spent her entire life selling dogmeat - a man is handed a plastic bag containing 12 dog paws. "My wife just gave birth but she's having trouble lactating," he explains. "There's an old recipe that calls for boiling the paws in a soup; we'll use that to help get her going again."

Each stall owner buys from suppliers who provide as many as 100 dogs a day, yet none of them knows where or how the dogs are sourced. Only one worker, Sy Le Vanh, a boyish 18-year-old slicing up carcasses at a family-run stall, says the dogs "must be Vietnamese". "I'm pretty sure our supplier used to get dogs from Thailand and Laos," he says, "but they were always so scrawny."

Pet ownership is still relatively new in Vietnam - dogs here have traditionally been reared for either food or security purposes - so campaigners have chosen to scrap the "cruelty" argument in favour of emphasising dogmeat's effect on people's health. It has been linked to regional outbreaks of trichinosis, cholera and rabies, a point activists underscore as the region looks to eradicate rabies by 2020. At the first international meeting on the dogmeat trade in Hanoi in late August, lawmakers and campaigners from Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam agreed on a five-point plan, including a five-year moratorium on the cross-border transportation of dogs for commercial purposes, in order to research the impact on rabies transmission.

The agreement might represent a significant policy shift, Dalley says, but may do little to wipe out the trade. "Through undercover investigators, we know the smugglers are already looking at alternative measures, including slaughtering dogs in Thailand and shipping carcasses as opposed to live animals." His foundation will be employing a full-time agent to monitor the border between Laos and Vietnam, he adds. "There will be a follow-up meeting in Bangkok, probably in the new year, and it will be embarrassing if they are still allowing dogs in."

Of the nations involved in the dogmeat trade, it is Thailand that is taking most action to curtail it. Once shipments are intercepted by Surasak's team, the dogs are sent to a government-run shelter in Nakhon Phanom, an hour north of the naval base, to be numbered, treated for infectious diseases such as parvo, distemper and pneumonia, and sent to one of the nation's four other shelters. Nearly 5,000 dogs, most rescued from the dogmeat trade, now live in these centres, according to Thailand's livestock department. Yet only a very small percentage will ever be rehomed, and around 30 dogs die every day from infection or disease.

It is impossible to imagine any of these animals as a potential food source, not because they are dogs, but because they are abysmally thin and desperately unhealthy. There are bony puppies with broken legs; mangy mutts oozing mucus from their eyes and noses; dogs covered in their own vomit and faeces; and the carcasses of those that have already died, in plastic bags, waiting to be buried. With only 12 staff and nearly 2,000 dogs to care for, survival here is a gamble, and as the shelter's Buddhist vets do not believe in "playing God", staff might administer medicine to a dying dog for months on end, until finally it is no longer able to move.

Many of those rescued from the dogmeat trade never even make it to Nakhon Phanom, Dalley says. "Of 1,965 dogs intercepted in January 2012 from a holding centre in Tha Rae and documented as being sent to [a shelter in] Buriram, 600 never arrived. We were told they'd died or run away, but they'd been sold back into the trade."

The navy's success in intercepting the traders has had the unintended effect of pushing the trade farther afield and underground, says Wiek, whose activist alliance has turned to alternative methods of surveillance - including drones and jetskis - the better to audit the business. "In the past few years, since the navy and other units have started to arrest more and more dog traders, and carry out raids on slaughterhouses, the trade has spread like a cancer," he says. It now extends from Tha Rae all across the north-east of Thailand.

Activists in Thailand are pushing for a new animal welfare law that would protect pets such as dogs and cats from being consumed or traded for consumption. But the law has little chance of making a real difference, Lohanan says. What may work instead is the opposite approach. Few in the Thai government openly oppose the trade, but one MP, Bhumiphat Phacharasap, has suggested that regulating dogmeat would stave off corruption and ensure that animals traded are fit for food. "We could treat dogs the same way we treat cows and pigs, by ensuring they were free of disease, had been vaccinated and had export licences, and hadn't been tortured or harmed in transportation," he says. "In Vietnam, they farm dogs just like they farm pigs and cows. I could accept that: you do it right, you eat it right. The problem is, we would be perceived as a culture that tortures animals because dogs are 'not for consumption'. We would be criticised. We'd be boycotted. We'd lose our trade rights [with the rest of the world]."

His worry is legitimate, at least for a culture dealing with the west, where researchers stress the historical human-dog bond and point to dogs' intelligence, using examples such as Chaser - a border collie whose vocabulary includes more than 1,000 English words - to prove their mental capacities are comparable to those of two-year-old children. But apologists say it is hypocritical for a culture that eats sheep, cows, pigs and chickens to draw the line at dogs. Pigs, for instance, do as well as primates in certain tests and are said by some scientists to be more advanced than dogs, yet many of us eat bacon without a second thought.

This is circuitous reasoning, as Jonathan Safran Foer has argued in his book Eating Animals. He points to dogs as a plentiful and protein‑rich food source, and asks: "Can't we get over our sentimentality?" He continues: "Unlike all farmed meat, which requires the creation and maintenance of animals, dogs are practically begging to be eaten. If we let dogs be dogs, and breed without interference, we would create a sustainable, local meat supply with low energy inputs that would put even the most efficient grass-based farming to shame."

His is an argument unlikely to win over many fans in the UK, the world's first country, in 1822, to make laws protecting animals from cruelty. It is a confounding issue, in part because it involves comparing cross-cultural mores with no clear answer. As the Australian philosopher Peter Singer put it in his 1975 work Animal Liberation: "To protest about bullfighting in Spain, the eating of dogs in South Korea, or the slaughter of baby seals in Canada while continuing to eat eggs from hens who have spent their lives crammed into cages, or veal from calves who have been deprived of their mothers, their proper diet and the freedom to lie down with their legs extended, is like denouncing apartheid in South Africa while asking your neighbours not to sell their houses to blacks."

Curious as to how this philosophy might play in Vietnam, I ask Duc Cuong, the doctor eating at the dogmeat restaurant, if it makes any difference to him that his meal could be someone's pet. "No," he says. "It's not my pet, so I don't really care."

may the end of the human race be sooner than later