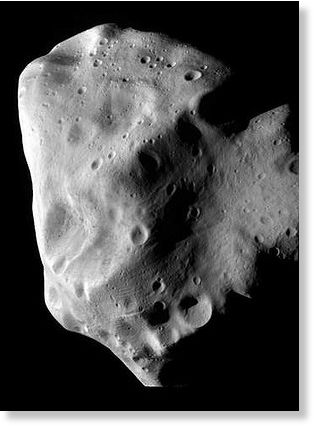

NASA is looking for a rock. It has to be out there somewhere - a small asteroid circling the sun and passing close to Earth. It can't be too big or too small. Something six to nine metres in diameter would work. It can't be spinning too rapidly, or a speed demon. And it shouldn't be a heap of loose material, like a rubble pile.

The rock, if it can be found, would be the target for what NASA calls the Asteroid Redirect Mission. Almost out of nowhere it has emerged as a central element of NASA's human spaceflight strategy for the next decade. Rarely has the agency proposed an idea so controversial among lawmakers, so fraught with technical and scientific uncertainties, and so hard to explain to ordinary people.

The mission, which could cost upward of $US2 billion ($2.2 billion), would use a robotic spacecraft to snag the small rock and haul it into a stable orbit around the moon. Then, according to NASA's plan, astronauts would blast off in a new space capsule atop a new jumbo rocket, fly towards the moon, go into lunar orbit, and rendezvous with the robotic spacecraft and the captured rock. They'd put on spacewalking suits, clamber out of the capsule, examine the rock and take samples. This would ideally happen, NASA has said, in 2021.

''That's our plan,'' said Michael Gazarik, NASA's head of space technology. ''We have to merge it with reality.''

NASA has what might be called middle-age problems. Founded 55 years ago, America's civilian space agency had its greatest glory in its youth, with moon exploration, and it retains much engineering talent and lofty aspirations. But even as the agency talks of expanding civilisation throughout the solar system, it has been forced to recognise its limitations. Flat budgets have become declining budgets. The joke among agency officials is that, when it comes to budgets, flat is the new up.

NASA lacks the money and the technology to do what it has long dreamed - to send astronauts to Mars and bring them safely back to Earth. It has resorted to fallback plans, and to fallbacks to the fallbacks.

Thus was born this improbable Asteroid Redirect Mission.

The human spaceflight program has long searched for a mission beyond Low Earth Orbit (LEO), where NASA has sent astronauts since the 1970s, and where the International Space Station circles the planet, currently occupied by two Americans, three Russians and an Italian. The asteroid mission not only goes beyond LEO, it scratches many other itches. NASA has marketed this as planetary defence - a way to get the upper hand on asteroids that could potentially smash into Earth. The agency also has said this could boost the commercial mining of asteroids for their minerals, thus expanding humanity's economic zone. And the robotic part of the proposal involves new propulsion technology that NASA thinks could be crucial for an eventual human mission to Mars.

There are also political factors. President Barack Obama vowed in 2010 to send humans to an asteroid. Moreover, the ensnared asteroid would provide a destination beyond LEO for new, expensive hardware NASA is already building: the big Space Launch System rocket and the Orion crew capsule. The mission could deflect charges the government is building rockets to nowhere.

''It is really an elegant bringing together of our exciting human spaceflight plan, scientific interest, being able to protect our planet, and utilising the technology we were already investing in,'' said Lori Garver, NASA's deputy administrator.

But the mission is viewed with scepticism by many in the space community.

At a July gathering of engineers and scientists at the National Academy of Sciences, veteran engineer Gentry Lee expressed doubt the complicated elements of the mission could come together by 2021 and said the many uncertainties would boost costs. ''I'm trying very, very hard to look at the positive side of this, or what I would call the possible positive side,'' he said.

''Of course, there's always luck. But how much money do you want to spend on a chance discovery that might have a very low probability?'' said Mark Sykes, a planetary scientist who chairs a NASA advisory group on asteroids.

If the target rock isn't scoped out well in advance, it could even turn out, on close inspection, to be something other than a small asteroid - say, a spent Russian rocket casing that's footloose around the sun.

NASA officials understand this and have recently been floating a different scenario, a Plan B. Instead of the robotic spacecraft trying to nab a small, little-understood and potentially unruly rock, the spacecraft could travel to a much larger, already-discovered asteroid and break off a chunk to bring back to lunar orbit, where astronauts would visit it.

That would eliminate a lot of unknowns. In space missions, unknowns ratchet up costs and create delays. But under Plan B, the target might be an underwhelming boulder the size of, say, a washing machine. Presumably that's not what Obama meant in 2010 when he vowed to send humans to an asteroid.

NASA is in a tricky position, trying to improvise a coherent strategy for human spaceflight even as political winds have shifted dramatically.

With the shuttle retired, NASA can no longer launch American astronauts on American rockets, but rather must buy seats at $US71 million a pop on Russian spaceships.The last space shuttle flew in 2011. NASA wants to see American astronauts ride to orbit on commercial spacecraft by 2017, though tight budgets could make that schedule slip by a year or more.

NASA's turmoil dates from February 1, 2003, when the space shuttle Columbia disintegrated over Texas, killing the seven astronauts on board. The grieving space community decided to rethink the enterprise of human spaceflight. Many people inside and outside of NASA wanted to get back to exploration, which would mean sending humans beyond Low Earth Orbit for the first time since the late 1960s and early 1970s. President George W. Bush proposed a plan to return astronauts to the moon by 2020 as part of a sustained lunar presence. The new NASA program, Constellation, included plans for two rockets, a crew capsule called Orion and a lunar lander.

But Constellation's funding fell short of what top NASA officials expected. The program fell behind schedule. Obama won the presidency, and Bush's Constellation program was soon gone. Obama's pick to run his NASA transition team, Lori Garver, never liked the back-to-the-moon strategy. ''If your goal is Mars, that is certainly a detour,'' she said recently.

In killing Constellation, Obama and his team adopted a ''flexible path'' strategy. The concept is arguably a sign of institutional maturity: NASA would focus less on destinations and more on creating new technologies. The idea was to advance spaceflight capabilities, with the long-term goal of sending people to Mars. Commercial companies could take over the routine taxi rides to orbit, and NASA would tackle harder missions. But there's a problem with the harder stuff: often it's just too hard.

Just about everyone in the space community wants to go to Mars. Rovers are great, but they're sluggish, and scientists fantasise about a human geologist being able to decide where to dig into the Martian soil for clues about the planet's history and possible signs of life. Many people feel strongly that societies that don't explore the frontier will invariably go into decline. A private venture called Inspiration Mars hopes to send two astronauts on a fly-by mission of Mars in 2018. And a Dutch reality show, Mars One, is lining up thousands of volunteers for a Mars colony that supposedly - and implausibly - will begin with landings in 2023.

NASA, however, is not an entrepreneurial outfit. Its plans have to pass multiple layers of technical, political and budgetary review. A fundamental presumption of NASA missions is that the astronauts will come back alive.

A journey to Mars would take about two years and expose astronauts to very high levels of radiation. The Martian atmosphere is a nightmare, just thick enough to cause problems but too thin to be of much use in braking a speeding spacecraft. NASA last year landed a 900-kilogram rover on Mars, but to put humans there, engineers think they would need to land 36,000 kilograms of payload, including a habitat, fuel and food.

More doable is a human mission that orbits Mars. Astronauts could essentially telecommute to work, operating rovers and other instruments from orbit. On April 15, 2010, in a closely watched speech at the Kennedy Space Centre, Obama said that by 2025, NASA will begin missions to ''deep space'', starting by ''sending astronauts to an asteroid for the first time in history''. Then would come a Mars orbital mission and landing in the mid-2030s, he said.

''I understand that some believe that we should attempt a return to the surface of the moon first, as previously planned,'' he said. ''But I just have to say pretty bluntly here: We've been there before.''

Months after Obama's speech, powerful senators from states with NASA centres and contractors took steps to salvage chunks of the Constellation program. Congress directed NASA to continue building a rocket that could take payloads beyond LEO. Orion would also proceed.

What the jumbo rocket and the Orion capsule can't do, without adding a lot of costly hardware, is fly to a distant asteroid orbiting the sun.

Just about any mission to an asteroid, even a ''near-Earth'' asteroid (one that's in an orbit that comes close to Earth) would take hundreds of days. The new Orion capsule can support astronauts for only about three weeks.

NASA, therefore, needed a fallback to the Obama-style asteroid mission. Hence the Asteroid Redirect Mission.

''He said humans to an asteroid,'' NASA's administrator, General Charles Bolden jnr, told The Washington Post. ''There are a lot of different ways to do that. I think we have come up with the most practical way, given budgetary constraints today. We're bringing the asteroid to us.''

Humans have never moved an object out of its natural orbit. Two years ago, engineers and scientists at the Keck Institute for Space Studies in Pasadena proposed doing just that with a small asteroid. The idea caught on in the corridors at NASA.

''It's not as crazy as it seemed at the beginning,'' said Charles Elachi, the longtime director of NASA's famed Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Elachi's people honed the mission and declared it feasible. What the laboratory doesn't have is a firm target for the asteroid mission. These objects are small, and appear fleetingly in telescopes, leaving behind minimal information about their size and composition. Without knowing the albedo - the shininess - of the object, it's impossible to know how big it is when that streak of light appears in the telescope.

NASA has an advisory committee of scientists who specialise in small objects in the solar system, and, after a meeting in July, the group produced a blistering draft report saying that NASA needed to do a lot more homework. For example, the report said: ''Such small objects may be rapidly rotating rubble piles, which could be hazardous to spacecraft during interactions with the target object.''

NASA used a small asteroid, dubbed 2009BD, as the hypothetical target in two feasibility studies, but that particular rock needs further scrutiny before anyone can say for sure that it would meet the requirements of the mission. It could be too small, a pipsqueak. It might not even be a natural object. The worst-case scenario would be the capture of something with Russian writing on the side.

So where does this leave the asteroid mission, and NASA? Back in a familiar place: with a plan that doesn't seem rock-solid.

Many times in recent months, officials have cited planetary defense as a reason for the mission. But the target rock would not be big enough to pose a threat should it hit Earth, and the methods used would not be applicable to the deflection of a large asteroid. In recent days, Bolden has backed off the save-the-Earth rhetoric.

Although NASA has publicly talked of an asteroid rendezvous in 2021, the idea has a fundamental problem. That is the first scheduled mission with a crew in the new Orion capsule. Officials in charge of getting astronauts home safely do not sound eager to conduct a shakedown cruise that involves complicated spacewalking and an interaction with a bagged asteroid in orbit around the moon.

In recent days, officials have suggested they could delay the asteroid mission until later Orion flights.

NASA has certain things going for it, including a track record of doing hard things very well.

''There have been 12 humans to walk on the surface of the moon. Guess what? Every single one of them was an American,'' Bolden said recently. ''Only one nation has successfully put something that operates on the surface of Mars. Guess what? That's the United States.''

Source: Washington Post

Comment: Guess what? America has sucked in space since it killed JFK, RFK, MLK and other fountains of creativity. Coincidence?

By the way, this is the same Bolden who said this in the aftermath of this year's asteroid blast above Russia:

Here's the video NASA showed Congress to try to convince it to fund this mad science project:

NASA is little more than a PR front for the Pentagon's space programs, which is why the agency has been putting ridiculous ideas into people's heads about 'saving the planet from asteroids'.

Even IF the Powers That Be know about the planet entering potential comet/asteroid debris fields, from the increased warmongering in the Middle East, does it look to you like they plan to do anything to physically stop or mitigate it?