© Motherboard

You should already know the name Yaneer Bar-Yam. He's the founding president of the New England Complex Systems Institute and

made news for a 2011 paper tying global food prices to 2008 and 2011 riot outbreaks in Africa, and the general theory that above a certain benchmark food price, the conditions for rioting become prime.

It's not a strict cause and effect relationship - if value

x, then riots - simply an observation that the probability of riots spikes at a certain point. Other things, like, say, Mohamed Bouazizi setting himself on fire, might be the actual trigger, but day-to-day survival as it pertains to food is what allows the gun to fire.

Bar-Yam's model has another "success," according to a

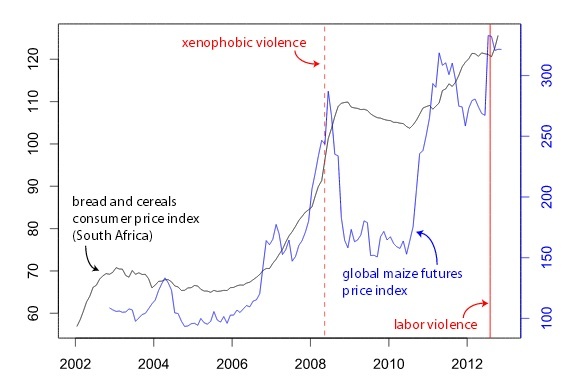

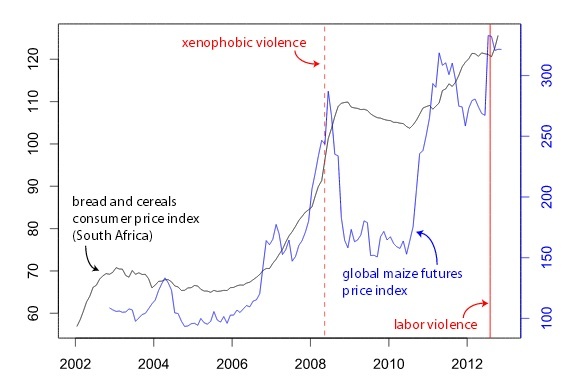

paper posted on the arVix pre-print server last week. Rioting that occurred last year during a platinum miner's strike in South Africa - in which 34 strikers were killed by government forces - coincided neatly with a spike in the global price of maize. Stagnant wages matched with spiking food costs yields unrest. It matches well with a similar spike in 2008 that resulted in another series of riots in the country.

The graph is below is limited to South Africa and fairly self-explanatory:

© Motherboard

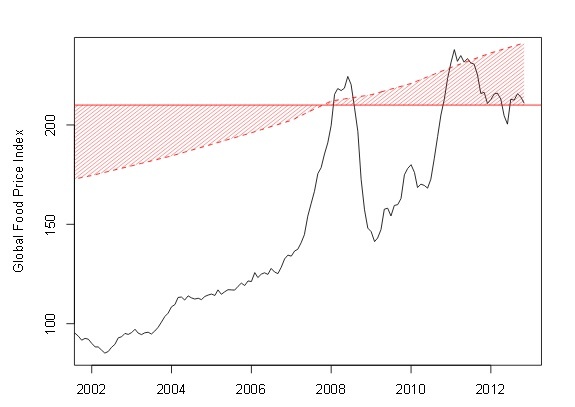

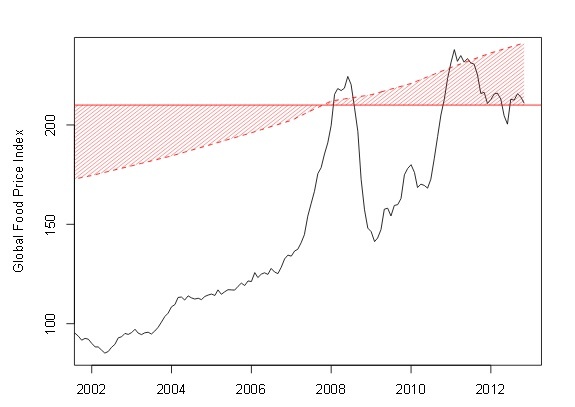

Furthermore, the model is being tested as you read this. The price of maize doesn't suddenly drop if you move to the right on the graph; as of today, the corn futures price is

$193.70, nudging the bottom of Bar-Yam's riot threshold, graphed below against the global food price index.

© Motherboard

The high price of maize ties to the United States, which produces the lion's share of corn worldwide yet dedicates much of that production to ethanol, not food, even in recent drought years. "Our analysis has shown that policy decisions that would directly impact food prices are decreasing the conversion of maize to ethanol in the US, and reimposing regulations on commodity futures markets to prevent excessive speculation, which we have shown causes bubbles and crashes in these markets," Bar-Yam

et all write. "Absent such policy actions, governments and companies should track and mitigate the impact of high and volatile food prices on citizens and employees."

An ominous twist is that corn producers in the U.S. are currently

growing more corn than the market is demanding. That is, the cost of corn for consumers is hovering at the edge of riot levels, while the selling price of corn is too low for producers. This has happened before, during the Great Depression and immediately preceding the Dust Bowl. Farmers ripped up fields for wheat and corn crops as fast as possible to make ends meet as the market price for corn tumbled, while in the eastern U.S., the country starved under catastrophic unemployment.

What followed shortly afterward was the black sky hell of the Dust Bowl drought. And, at the moment, the United States' corn producing regions remain in a drought second only to the Dust Bowl. It's an epic and confusing mess of circumstances with that distorted echo of some of America's worst years. A notable difference is that the world is much more global now, with our Dust Bowl resonating in even more vulnerable parts of the world. Unfortunately, Bar-Yam's model is about to see many more tests.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter