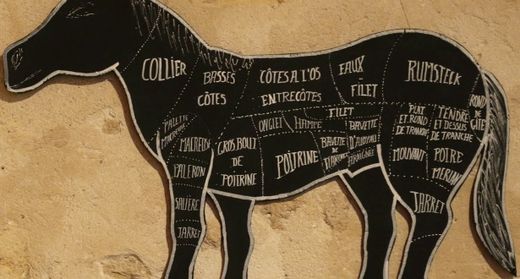

© Christian Hartmann/Reuters

Everyone who seriously studies French or Italian food on scholarly (gluttonous) research trips eats horsemeat. Most every village in France, particularly the southwest and northern border regions with Belgium, and in Italy, particularly the northeast around Verona and Venice, will have a butcher shop specializing in horsemeat, marked with disconcerting gilded horseheads over the shop windows revealing trays of bright lean red meat. Anyone who visits Eastern Europe, especially the Stans, is likely to be used into a restaurant whose specialty is horse cuisine. It's a rite of passage, like watching a pig slaughter and eating fresh blood pudding right afterward.

So I've had horse tournedos, horse sausage, and horse ragu. Several times. For reasons I'll explain, I wasn't eager to continue this line of exploration. But given the recent storm in the media over tainted burgers and ground beef in Europe and possibly all over Europe, I did look further into why eating horse, a seemingly archaic custom that should have died along with other staples of the paleo diet, has persisted.

First, for catchup on what the discovery of horse DNA implies about food safety and what corrective measures might ensue, see

Marion Nestle's chronological links. For a good summary of the media's reaction, see Jack Shafer's

column (and the

Dish debate it provoked).

Shafer was quick to see the main point: this is news because of cultural taboos and the big ick factor of eating animals to which we ascribe -- that is, willfully project -- personality and character. It's a sharper, more painful, but similar reaction to anyone who encounters a restaurant or, worse, butcher selling dog meat in China. (For overviews on the ethics of eating meat at all, it's always worth revisiting our columns by

James McWilliams and

Nicolette Hahn Niman.)

Avoidance of horse is as ancient as it is inconsistent. Greek butchers sold it as cheap meat, according to the

Grande Enciclopedia Illustrata Della Gastonomia, edited by Marco Gotti Guarnaschelli. The early Catholic church, according to the Penguin Companion to Food, banned horsemeat likely because of its association with pagan sacrifice and ritual eating; it is unkosher as horses aren't ruminants and don't chew their cud; Muslims ban it, possibly because horses were luxury animals in oases (though all theories about emotional attachment to animals' enjoining their consumption should be looked at with suspicion); Hindus also proscribe it.

Yet prehistoric Europeans ate horse, and barbaric tribes did too, probably because it was an efficient way to dispose of old or limping animals. And horse is the original steak tartare, named for the horsemen of Genghis Khan, possibly because horsemeat doesn't spread either tuberculosis or tapeworms and was thus safer to eat raw than other kinds of meat and fish. It is also leaner and higher in protein and iron than some other red meats -- and much cheaper, which led to its promotion as a health food for the working class.

The modern European acceptance of horsemeat gained its greatest strength in France. Ending shibboleths against horsemeat was a late aftereffect of the Enlightenment: Antoine-Augustin

Parmentier, Napoleon's pharmacist and then health minister who is remembered for convincing the French that the potato wasn't poisonous, also tried to win acceptance for horsemeat, which according to

Larousse Gastronomique was illegal until 1811.

Possibly fearing the reliance of the working classes on the potato and seeing the Irish Potato Famine of the 1840s, and wanting to stay competitive in the Industrial Revolution, the French government in 1853 set minimum daily intake regulations of 100-140 grams of proteins for adults (who knew that the French got into the minimum-daily-requirement business so early? This according to the

Cambridge World History of Food).

Horsemeat seemed the way to fuel the Industrial Revolution: it was cheap, plentiful, and high-protein. The French promoted it as a health food and claimed that it reduced the urge to drink too much. As of 1866 horsemeat shops had opened in Paris, and the year before, a demonstration feast at the Grand Hotel served horse in nearly every course to intellectuals including Flaubert and Dumas. The menu, Larousse says, included vermicelli in horse broth, horse sausage and cured meats, boiled horsemeat and fillet with mushrooms, horse stew, potatoes sautéed in horse fat, salad in horse oil, and rum cake with horse-bone marrow. The wine was Cheval Blanc.

Oddly, news of this menu did not dissuade the entire French populace from consuming horse. It cost half what beef did. People ate it more because they could afford it than because they liked it -- the high content of glycogen that makes horse lean and high in protein also makes it taste sweet.

Despite its resistance to other pathogens, horse is more susceptible to spoilage than other meats. In 1967, a salmonella outbreak in a French school cafeteria resulted in its banning for schoolchildren.Pockets of hippophagy, though -- a word that might start entering spelling bees after the recent scandals -- persist. Not just in the Stans but in Italy, where the dish I was repeatedly served on a culinary trip around the Veneto was pastissada, a stew whose origins are supposedly a bloody battle between one medieval king of Italy named Odoacer and the rival who became his successor, the Ostrogoth (read barbarian) Theodoric. The legend says that the dish was invented so as not to waste the dead animals, but perhaps it was eaten at a dinner of reconciliation to which Theoderic invited Odoacer and then killed him.

Odd that such sour origins could give rise to such a sweet stew. Strangely sweet. Disturbingly sweet: because of its high glycogen content, horsemeat as a fillet, which is tender and lean, has the look and texture of bison but the sweetness of dessert-y things I don't want to think about in the context of a meat course, even if I'll eat (grudgingly) mincemeat pie. Pastissada has a lot of clove and other sweet spices, along with sweet pepper -- it's something like a goulash, which makes sense given the Veneto's period of Austro-Hungarian domination. And you can always concentrate on the polenta it comes with.

But until my next trip to Kazakhstan or Romania, where I'll be served horsemeat wittingly or not -- or, of course, my next visit to an Irish burger place -- I'll stay an avowed, if experienced, hippophagy-phobe.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter