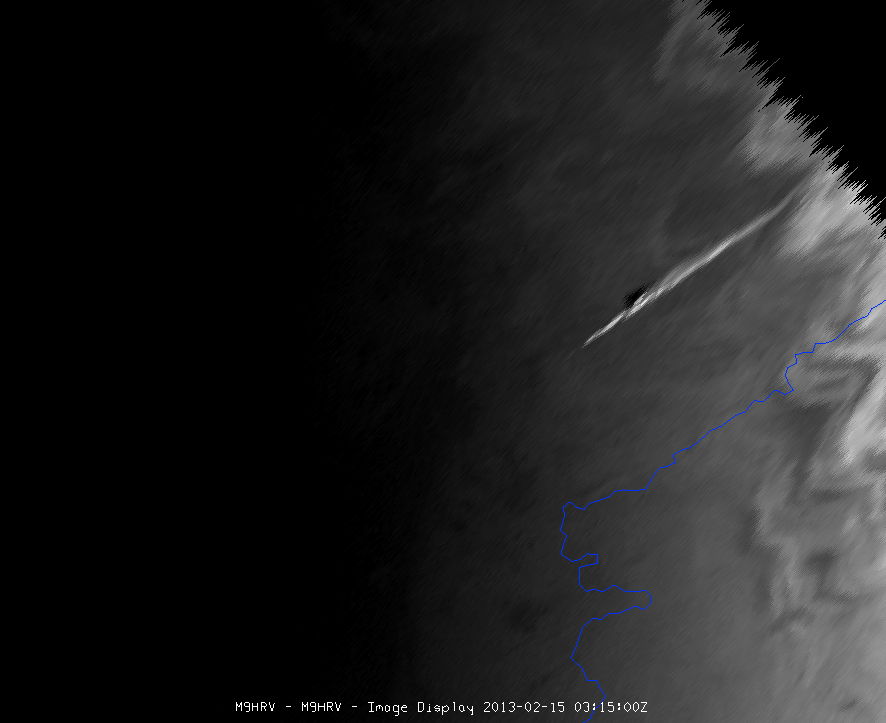

The meteor which exploded over the Urals of central Russia was seen by Meteosat-9, at the edge of the satellite view. Hundreds of people were reportedly injured as the meteor's massive sonic boom caused widespread damage.

It's fireball season on Earth, and it is starkly clear for residents in eastern Russia where a bright fireball exploded in the atmosphere early today (Feb. 15).

Comment: The only sense in which it is 'Fireball Season' is that these next few months and years are going to see a whole lot more fireballs than usual.

For reasons scientists don't quite understand, there appears to be an increase in the number of bright meteors visible blazing through the night sky during the month of February. The notion hit home today when a meteor exploded over Russia's Ural Mountains, injuring more than 900 people and damaging thousands of buildings, according to press reports. (Another space rock, the asteroid 2012DA14, is on course to pass very close to Earth Friday evening, but will not hit the planet.)

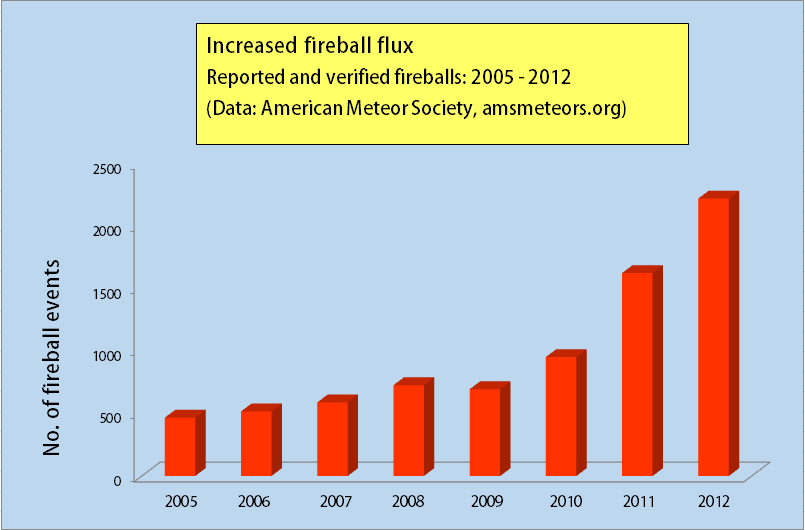

Comment: Yes, they noticed a string of bright fireballs in February last year, so they invented the term 'February Fireballs.' But then bright fireballs continued to appear so they called the next cluster the 'April Fireballs', and so on. They won't just come straight out and tell you that fireballs are increasing all the time:

On a typical night of the year, stargazers might see about 10 "sporadic" fireballs, created by fragments of asteroids or comets that burn up in the Earth's atmosphere. But that number spikes by 10 to 30 percent during the spring. The fireballs come from the asteroid belt, but their exact source remains unknown.

Meteor enthusiasts have known about the "Fireballs of February" since the 1960s and 70s, when amateur astronomers noticed many more bright, sound-producing streaks than usual. Follow-up studies during the 1980s failed to show any increase in the rate of fireballs, but a 1990 study suggested otherwise.

Comment: They could easily refer to the American Meteor Society's fireball report statistics to verify a significant increase in fireball sightings in the past 6-7 years.

Bill Cooke, NASA's PR guy, is making stuff up as he goes along when he says

"We've known about this phenomenon for more than 30 years," Cooke said. "It's not only fireballs that are affected. Meteorite falls - space rocks that actually hit the ground - are more common in spring as well."There is no scientific literature on this so-called "phenomenon going back 30 years".

Astronomer Ian Holliday studied photographic records of roughly a thousand fireballs from the 1970s and 80s, finding what looked like a fireball stream crossing Earth's orbit during February, late summer and fall. Halliday's results are somewhat controversial, but the phenomenon appears real.

Comment: One possible explanation for this is the recent break-up of a comet whose train of debris the planet transects every year. But then, fireballs are reported all the time, so that would suggest that multiple large bodies have entered into, and broken up in, the inner solar system...

The February fireball increase is somewhat puzzling because the number of ordinary meteors normally peaks during autumn in the Northern Hemisphere, according to researchers at NASA's Meteoroid Environment Center. The two most visible meteor showers most years, the Perseid meteor shower and the Leonid meteor shower, peak in mid-August and mid-November.

Scientists are probing the mystery of the spring surge in fireballs using NASA's All-Sky Fireball Network, a slew of cameras designed to observe meteors brighter than the planet Venus. The data collected could reveal where these fireballs come from, scientists say. Modeling the meteoroid environment will also benefit spacecraft designers.

Comment: It is not just February that has seen a large increase in fireballs - they have been increasing in frequency in all seasons in recent years!

Celestial Intentions: Comets and the Horns of Moses is a must-read to understand just what the heck is going on here.