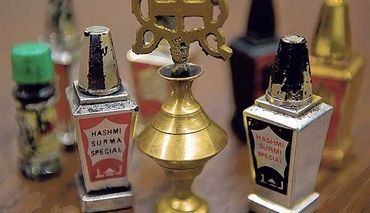

© Clifford Oto/The RecordExamples of surma, a lead-based makeup made in Pakistan and India.

The 1-year-old girl was playing "makeup" with her mother.

Every day, mom brushed a fine black powder, known as surma, around the little girl's eyes - a practice common in Pakistani and Indian cultures, to both enhance a child's beauty and to ward off the "evil eye."

But public health nurse Gail Heinrich knew it wasn't the evil eye this girl had to worry about.

Surma is rich in toxic lead. A child who touches her face with her hands, then sticks her hands in her mouth, could be ingesting enough lead to damage her rapidly developing brain.

Indeed, tests showed this little girl was suffering from lead poisoning. She endured five days of treatment at Children's Hospital Oakland, but too much damage had been done.

"(The girl's mother) called me about a year and one-half later, and the child was on special education," said Heinrich, who coordinates a child lead poisoning program for San Joaquin County Public Health Services.

"It's really sad," she said.

It's also alarming, when you consider the increase in lead poisoning cases that can likely be attributed to the use of surma.

In a public warning issued earlier last week, Heinrich reported that 14 out of 44 lead poisoning cases discovered in children last year were believed to involve the use of surma. That's about 31 percent.

Compare that to 2008, when surma cases accounted for about 4 percent of Heinrich's workload.

More families of Pakistani and Indian origin have moved to the area, she said, probably accounting for the increase.

The difficulty is making them aware of the danger - and convincing them to give up a tradition that spans generations.

"They'll say, 'Well, my grandparents used this, and everyone is fine. How could this be a problem?' " Heinrich said.

"The problem is, how do you tell someone how smart they could have been? Or that their IQ could have been this, but it's this instead?"

The Pakistani American Association of San Joaquin County sent an email blast to its members last week after Public Health issued its warning, said association leader Shakir Awan.

He said the association could work with Public Health to develop educational materials to be made available for young parents in hospitals at the time of birth and also in schools.

Perhaps doctors could be recruited to explain the problem to the Pakistani people when they gather for Friday afternoon prayers at local Islamic centers and mosques, Awan said.

"A lot of the time, I think it's educational," said Waqar Rizvi, another member of the association. "Any parent would be concerned if they find out it's poisonous."

He said that while surma use may be widespread in parts of Pakistan, he doesn't see much of it here.

But in a Public Health conference room on Friday, Heinrich arranged seven tiny vials on a table, each containing surma or other toxic variations found in local homes.

These have been banned for import into the United States, but they still show up in the suitcases of travelers or through illegal distribution to retailers.

They resemble simple eyeliner or mascara containers. But many families won't switch to the nontoxic cosmetic products for fear they will not fulfill the role of warding off evil, Heinrich said.

The goal is to teach families about surma - not to punish them, Heinrich said. Yet access to their homes has been difficult because many fear they'll be in trouble.

"This isn't just uneducated families," Heinrich said. "We've got families that are very prominent in the community who are using this.

"But kids these days are having such a hard time as it is. We don't need to add lead poisoning and brain damage to it."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter