Hailed by Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon as a major step forward in protecting women and girls and ending impunity for the harmful practice, the text is expected to be endorsed by the UN general assembly this month.

How did the practice begin anyway?

Although theories on the origins of FGM abound, no one really knows when, how or why it started.

"There's no way of knowing the origins of FGM, it appears in many different cultures, from Australian aboriginal tribes to different African societies," medical historian David Gollaher, president and CEO of the California Healthcare Institute (CHI), and the author of Circumcision, told Discovery News.

Used to control women's sexuality, the practice involves the partial or total removal of external genitalia. In its severest form, called infibulation, the vaginal opening is also sewn up, leaving only a small hole for the release of urine and menstrual blood.

While the term infibulation has its roots in ancient Rome, where female slaves had fibulae (broochs) pierced through their labia to prevent them from getting pregnant, a widespread assumption places the origins of female genital cutting in pharaonic Egypt. This would be supported by the contemporary term "pharaonic circumcision."

The definition, however, might be misleading. While there's evidence of male circumcision in Old Kingdom Egypt, there is none for female.

"This was not common practice in ancient Egypt. There is no physical evidence in mummies, neither there is anything in the art or literature. It probably originated in sub-saharan Africa, and was adopted here later on," Salima Ikram, professor of Egyptology at the American University in Cairo, told Discovery News.

Historically, the first mention of male and female circumcision appears in the writings by the Greek geographer Strabo, who visited Egypt around 25 B.C.

"One of the customs most zealously observed among the Egyptians is this, that they rear every child that is born, and circumcise the males, and excise the females," Strabo wrote in his 17-volume work Geographica.

A Greek papyrus dated 163 B.C. mentioned the operation being performed on girls in Memphis, Egypt, at the age when they received their dowries, supporting theories that FGM originated as a form of initiation of young women.

Other writers later explained that the procedure was carried for less ritualistic reasons.

According to the 6th century A.D. Greek physician Aetios, the cutting was necessary in the presence of an overly large clitoris.

Seen as "a deformity and a source of shame," the clitoris would produce irritation for its "continual rubbing against the clothes" thus "stimulating the appetite for sexual intercourse."

"On this account, it seemed proper to the Egyptians to remove it before it became greatly enlarged, especially at that time when the girls were about to be married," Aetios wrote in The Gynecology and Obstetrics of the Sixth Century A.D.

According to U.S. historian Mary Knight, author of the paper "Curing Cut or Ritual Mutilation?: Some Remarks on the Practice of Female and Male Circumcision in Graeco-Roman Egypt," medical motivations probably mixed with ritual, social and moral reasons to favor "the continuation of a practice that initially may have been narrowly performed and whose original motivation most likely had long been forgotten."

Many centuries later, 19th century gynaecologists in England and the United States would perform clitoridectomies to treat various psychological symptom as well as "masturbation and nymphomania."

"The surgeries we see in Victorian England and America were generally based on a now discarded theory called 'reflex neurosis,' held that many disorders like depression and neurasthenia originated in genital inflammation," Gollaher said.

"The same theory was behind the medicalization of male circumcision in the late 19th century," he added.

It is only relatively recently that FGM has been recognized internationally as a violation of the human rights of girls and women.

Sweden was the first Western country to outlaw FGM, followed in 1985 by the UK. In the United States it became illegal in 1997, and in the same year the WHO issued a joint statement with the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) against the practice. FGM is a crime in many countries now.

Last week the head of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation also called for abolishing female genital mutilation.

"This practice is a ritual that has survived over centuries and must be stopped as Islam does not support it,"Secretary-General Ekmeleddin Ihsanoglu said at the intergovernmental organisation's 4th conference on the role of women in development, in Jakarta, Indonesia.

An estimated 140 million girls and women now alive have undergone the mutilating procedure in 28 African countries, as well as in Yemen, Iraq, Malaysia, Indonesia and among certain ethnic groups in South America and some immigrant communities in the West.

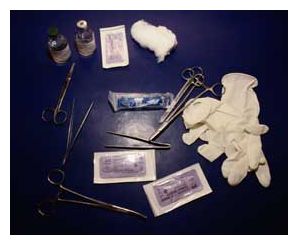

About three million girls in Africa are said to be forced to undergo the procedure each year. The cutting is often done without anaesthetic, in conditions that risk potentially fatal infection -- often using scissors, razor blades, broken glass and tin can lids.

Although not legally binding, the UN resolution carries considerable moral and political weight.

I don't see a similar resolution coming out on behalf of males, being that male mutilation is a "sacred" thing among some peoples, peoples who incidentally wield enormous power and can bend UN initiatives and eventually bury them in the sand. Add to this the myth that said male mutilation is advanced as good for hygiene by so-called health "experts", so it becomes all the more difficult to support a successful move towards a ban of male mutilation.