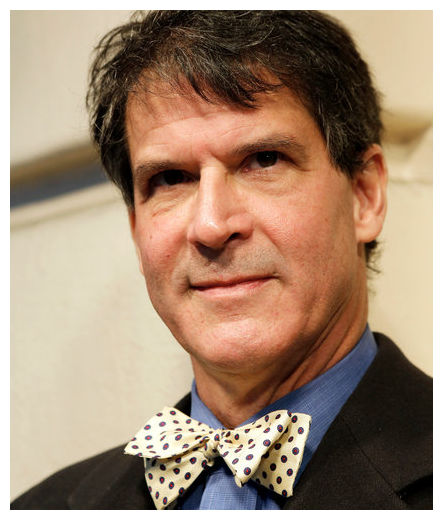

© Jennifer Taylor/The New York TimesDr. Eben Alexander III

For years Dr. Eben Alexander III had dismissed near-death revelations of God and heaven as explainable by the hard wiring of the human brain. He was, after all, a neurosurgeon with sophisticated medical training.

But then in 2008 Dr. Alexander contracted bacterial meningitis. The deadly infection soaked his brain and sent him into a deep coma.

During that week, as life slipped away, he now says, he was living intensely in his mind. He was reborn into a primitive mucky Jell-o-like substance and then guided by "a beautiful girl with high cheekbones and deep blue eyes" on the wings of a butterfly to an "immense void" that is both "pitch black" and "brimming with light" coming from an "orb" that interprets for an all-loving God.

Dr. Alexander, 58, was so changed by the experience that he felt compelled to write a book, "Proof of Heaven," that recounts his experience. He knew full well that he was gambling his professional reputation by writing it, but his hope is that his expertise will be enough to persuade skeptics, particularly medical skeptics, as he used to be, to open their minds to an afterworld.

Dr. Alexander acknowledged that tales of near-death experiences that reveal a bright light leading to compassionate world beyond are as old as time and by now seem trite. He is aware that his version of heaven is even more psychedelic than most - the butterflies, he explained, were not his choice, and anyway that was his "gateway" and not heaven itself.

Still, he said, he has a trump card: Having trained at Duke University and taught and practiced as a surgeon at Harvard, he knows brain science as well as anyone. And science, he said, cannot explain his experience.

"During my coma my brain wasn't working improperly," he writes in his book. "It wasn't working at all."

Simon & Schuster, which released the book on Oct. 23, is betting that it can appeal to very different but potentially lucrative audiences: those interested in neuroscience and those interested in mystical experiences. Already Dr. Alexander has been a guest on

The Dr. Oz Show and is scheduled to appear as the sole guest of an hourlong special with Oprah Winfrey on Sunday.

"This book covers topics that are of interest to a lot of people: consciousness, near death, and heaven," said Priscilla Painton, the executive editor at Simon & Schuster, who acquired the book.

The company took the unusual step of releasing the book in hardcover, paperback and e-book format, so it could simultaneously sell to a wider range of readers - at Walmarts and grocery stores as well as independent bookstores and online. It rose instantly to No. 1 on

The New York Times's paperback best-seller list and is there again for next week.

Ms. Painton would not elaborate on what type of audience the book had attracted so far, but she did say she expected it to continue to be a big seller. The publisher has printed nearly one million copies, combined hardcover and paperback, to be snapped up at airports and as stocking stuffers at big retailers like Target. Another 78,000 digital copes have been sold.

In a recent interview at the Algonquin Hotel lobby in Manhattan, however, Dr. Alexander made it clear that he was less interested in appealing to religious "believers," even though they had been a core audience for similar books.

He rejected the idea that readers of his book would be the same as those who bought

Heaven Is for Real, a 2010 mega best-seller about a preacher's son who sat on Jesus' lap during a near-death experience.

"It is totally different," he insisted. "Those who believed in heaven when they read the book were not happy. They didn't like the title. They say, 'This is not scientific proof.' "

In fact, he said,

Proof of Heaven was not his idea for a title. He preferred "An N of One," a reference to medical trials in which there is only a single patient.

Wearing a yellow bow tie, Dr. Alexander talked about his career and his years at Harvard, sounding every bit the part of a doctor one might trust to drill open skulls and manipulate their contents.

He left Harvard in 2001, he said, because he was tired of "medical politics." In 2006 he moved to Lynchburg, Va., where he did research on less invasive forms of brain surgery through focused X-rays and digital scanners. Then the meningitis felled him.

After recovering, he originally planned to write a scientific paper that would explain his intensely vivid recollections. But after consulting the existing literature and talking extensively to other colleagues in the field he decided no scientific explanation existed.

"My entire neocortex - the outer surface of the brain, the part that makes us human - was entirely shut down, inoperative," he said.

He hesitated nevertheless. It took him two years, he said, to even use the word God in discussing his experience. But then he felt an obligation to all those dealing with near-death experience, and particularly to his fellow doctors. He felt compelled to let them know.

So far he has spoken at the Lynchburg hospital, where he was treated, and said he has been invited to address a group of neurosurgeons at Stanford.

But these invitations, he acknowledged, do not mean that his theory is gaining ground among doctors. In private conversations, he said, very few of his colleagues offered counterarguments. Some agreed with his conclusion that science could not explain what he saw, but none of them were willing to be named in his book.

Other former colleagues reached for comment were not convinced. Dr. Martin Samuels, chairman of the neurology department at Brigham and Women's Hospital, a Harvard teaching affiliate, remembered Dr. Alexander as a competent neurosurgeon. But he said: "There is no way to know, in fact, that his neocortex was shut down. It sounds scientific, but it is an interpretation made after the fact."

"My own experience," Dr. Samuels added, "is that we all live in virtual reality, and the brain is the final arbiter. The fact that he is a neurosurgeon is no more relevant than if he was a plumber."

Dr. Alexander shrugs off such analysis. He still hopes to tour "major medical centers and hospices and nursing homes," he said, to relate his experience in distinctly medical environments.

His messages to those who deal with dying is one of relief. "Our spirit is not dependent on the brain or body," he said. "It is eternal, and no one has one sentence worth of hard evidence that it isn't."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter