One of the artifacts in question is the Greville Chester toe, now in the British Museum. It dates back before 600 B.C. and is made of cartonnage, an ancient type of papier maché made with a mixture of linen, animal glue and tinted plaster. The other is the wood and leather Cairo toe at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, which was found on a female mummy near Luxor and is thought to date back to between 950 and 710 B.C.

If the parts were indeed used to help ancient Egyptians missing a big toe walk normally, they would be the earliest known practical prostheses - older than the bronze and wooden Roman Capua leg, which dates back to 300 B.C.

"Several experts have examined these objects and had suggested that they were the earliest prosthetic devices in existence," University of Manchester researcher Jacky Finch, who led the study, said in a statement. "There are many instances of the ancient Egyptians creating false body parts for burial but the wear plus their design both suggest they were used by people to help them to walk."

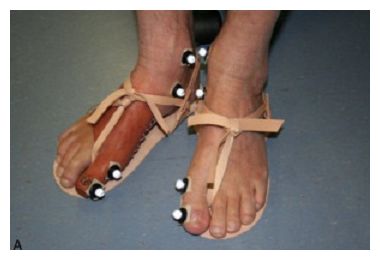

To help prove this claim, Finch recruited two volunteers who were both missing their right big toe and outfitted them with replicas of the ancient fake toes and replica Egyptian sandals. The volunteers then walked 33 feet (10 meters) barefoot, with shoes on and then with the replica toes with and without sandals. Finch recorded their movements and measured the pressure of their footsteps with a special mat.

Meanwhile, the second volunteer got between 60 and 63 percent flexion wearing the replicas with and without the sandals, according to a statement from the University of Manchester.

The false toes also did not cause any high pressure points for the two volunteers, suggesting the prosthetics were relatively comfortable. But wearing the sandals without the artificial toes caused pressure under the foot to rise sharply, the researchers said.

"The pressure data tells us that it would have been very difficult for an ancient Egyptian missing a big toe to walk normally wearing traditional sandals," Finch said in a statement from the university, adding that her research suggests these false toes made walking in a sandal more comfortable.

The study was published in this month's issue of the Journal of Prosthetics and Orthotics.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter