The lake's water comes from ice melting from the Colonia Glacier, located in the Northern Patagonian ice field, some 2,000 kilometers (1,250 miles) south of the capital, Santiago.

The glacier normally acts as a dam containing the water, but rising temperatures have weakened its wall. Twice this year, on January 27 and March 31, water from the lake bore a tunnel between the rocks and the glacier wall.

The result: Lake Cachet II's 200 million cubic liters of water gushed out into the Baker river, tripling its volume in a matter of hours, and emptying the five square kilometer (two square miles) lake bed.

Cachet II has drained 11 times since 2008 -- and with global temperatures climbing, experts believe this will increase in frequency.

"Climate models predict that as temperatures rise, this phenomenon, known as GLOFs (Glacial Lake Outburst Floods), will become more frequent," said glaciologist Gino Casassa from the Center for Scientific Studies (CES).

Casassa, a member of the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize-winning Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, told AFP there have been 53 similar cases of lakes draining in Chile between 1896 and January 2010, with increased frequency in the later years.

CES research assistant Daniela Carrion was camped out with a small research team taking measurements of the Colonia Glacier when the lake drained in March.

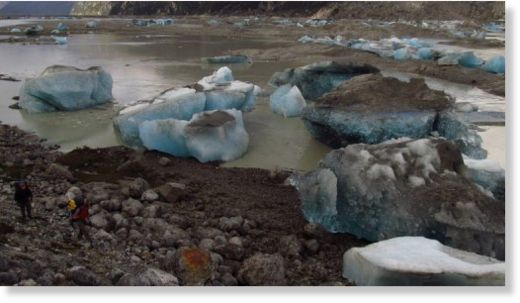

"When we woke up, we saw a change in the valley," Carrion told AFP. "The paths that we walked on had flooded, and the whole area was filled with large chunks of ice."

The lake dropped 31 meters (90 feet) when the water drained out, according to a report from the General Water Directorate, which monitors lake levels in Chile using satellite data.

When the lake starts draining an alarm system is triggered, giving residents in the sparsely-populated area up to eight hours to move animals and flee to higher ground.

The Tempanos Lake, also in far southern Chile, drained in a similar fashion in May 2007. Forest rangers working to save endangered huemuls -- mid-sized deer native to the region -- were surprised when they came across the empty lake. There were ice floes on the floor of the ten square kilometer lake bed, but no water.

Forestry officials had visited Tempanos in April and it was full, and when a team of scientists and naval officials flew over the area in July they found that the lake, which also is fed by waters from a nearby glacier, was starting to re-fill.

The GLOF phenomenon is not exclusive to Patagonia: it has happened in places like the Himalayas, and in Iceland due to volcanic activities, Casassa said.

In a phenomenon also related to rising temperatures, a slab of ice the size of a city block broke off Peru's Hualcan glacier and slid into a high mountain lake with destructive consequences in April 2010.

The crash unleashed a giant wave that breached the lake's levees, causing a tsunami of mud on a village in the northern province of Carhuaz that destroyed more than 20 homes and leaving some 50 people homeless, regional Civil Defense chief Cesar Velasco told the state Andina news agency.

A 2009 World Bank report said that in the last 35 years, Peru's glaciers have shrunk by 22 percent, leading to a 12 percent loss in the amount of fresh water reaching the coast, home to most of the country's citizens.

....for listening to a stranger.