© redOrbit

An Australian archaeologist has discovered ancient fish bones in a cave in East Timor - a small island country northeast of Australia in the Lesser Sunda Islands - that contain the ancient remains of more than 38,000 fish bones from nearly 2,900 individual fish, a sign that humans may have gone deep-sea fishing as many as 42,000 years ago.

Among the fish bones were those of tuna and shark, clearly brought to the cave - called

Jerimalai - by human hands. And to back that up, the archaeologist also unearthed a fish hook dating to 23,000 years old.

The discovery, reported online in the journal

Science, provides the strongest evidence yet that people were deep-sea fishing long ago. And those maritime skills may have allowed the inhabitants of this region to travel abroad and colonize other islands and continents.

Human consumption of fish dates back around 1.9 million years. Early fishers waded into lakes and streams and caught fish without the use of boats or complex tools. It wasn't until later that humans began fishing the deep seas.

The earliest known boats, found in France and the Netherlands, date back only 10,000 years, but archaeologists know that boats must have been used prior to this. Wood and other common boat-building materials do not preserve well, making it harder to find more ancient proof. But. With the colonization of Australia and nearby islands in Southeast Asia occurring at least 45,000 years ago, sea travel of at least 16 miles would have been required.

Modern humans had been utilizing near-shore resources - mussels, abalone, etc.. - as early as 165,000 years ago, but direct evidence of early seafaring skills has eluded scientists and archaeologists for ages. A few controversial sites have suggested that our early ancestors had fished deep waters 45,000 years ago, but the earliest sure sites are only about 12,000 years old.

But the new find, discovered by Susan O'Connor, an archaeologist at the Australian National University in Canberra, may prove that our human ancestors did ply the deep-sea waters long before we had previously believed.

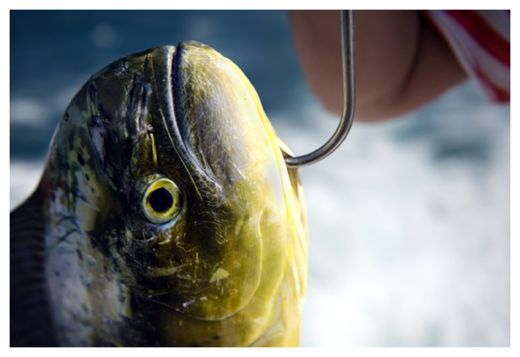

Using dating techniques, O'Connor and her colleagues determined dated the earliest levels of Jerimalai Cave to 42,000 years ago. In those early levels, the team found fish bones of tuna and shark, both of which thrive in deep-sea waters. The unearthing of the fish hook, made from a mollusk shell, dated to about 23,000 years ago. The team claims the hook is the earliest definitive evidence for line fishing.

Since catching tuna and shark requires tools and advance planning, O'Connor said these people must have developed the mental and technological skills to exploit the sea. She noted that about 50 percent of the fish in the cave were that of deep water fish, the rest were shallow water species, such as Parrot Fish.

Our evidence "certainly suggests that people had advanced maritime skills" 42,000 years ago, O'Connor said. The finds indicate that this mastery of the sea "must have been one of the things that allowed the initial colonization" of East Timor and other Southeast Asian islands.

But, O'Connor cautions, there is still no direct evidence about the maritime skills of the first people who colonized Australia, leaving open the possibility that they drifted there with the tides.

"It increases our insight into the developing abilities of early modern people," Eric Delson, an anthropologist at Lehman College of the City University of New York, who was not involved in the new study, told the Associated Press (AP) by email.

Early anglers probably fashioned boats by tying logs together and used nets and sharpened pieces of wood or shells as hooks, said Kathlyn Stewart, a research scientist at the Canadian Museum of Nature, who was not part of the study. "These people were smart," she told AP's Alicia Chang. They knew "there were fish out there."

It's unclear how far the early mariners ventured, however. Once they caught their food, they likely ate it raw or went back to camp to cook it, Stewart added.

O'Connor said it was unclear how they caught ocean fish, because no fishing gear was found in the cave, apart from the hook. Along with the one hook fashioned from mollusk shell, the team did uncover other smaller hooks, although they did not seem suitable for deep-sea fishing.

"The hooks were definitely used for ocean fishing but we can't be sure which species," O'Connor said. "The hooks don't seem suitable for pelagic fishing, but it is possible that other types of hooks were being made at the same time."

What's still unknown is how these ancient people were able to catch these fast-moving deep-ocean fish.

"It's not clear what method the occupants of Jerimalai used to capture the pelagic fish or even the shallow water species. But tuna can be caught in purse seines or leader nets, or by using hooks and trolling. Simple fish aggregating devices such as tethered logs can also be used to attract them. So they may have been caught using hooks or nets. Either way it seems certain that these people were using quite sophisticated technology and watercraft to fish offshore," said O'Connor in a press release.

Archaeologist James O'Connell of the University of Utah, who has argued that "a broad range of evidence" points to deep-sea fishing between 45,000 and 50,000 years ago, told Science Now that the new evidence from O'Connor's excavation "solidifies the case."

But William Keegan, an anthropologist at the Florida Museum of Natural History in Gainesville, points out that the relatively small size of the tuna found at Jerimalai - mostly between 20 and 28 inches long - suggests that they were juvenile fish that may have been caught close to shore.

And Geoff Bailey, an archaeologist at the University of York in the United Kingdom points out that East Timor and the other islands in the area have very steep offshore topography, meaning that the deep waters favored by adult tuna and sharks are very close to land.

These species "would likely come very close inshore," allowing humans to catch them without necessarily requiring the use of boats, Bailey noted.

O'Connor countered that even juvenile tuna are "fast moving," adding that "there is no way they could be speared off the beach or the reef." Fishing hooks and other evidence of maritime technology have yet to be found in the earliest levels at Jerimalai, but she and her team plan to continue excavating there in an attempt to find them.

It is entirely possible that these larger fish, for which no easy explanation is available, simply washed up on the beach. It happens today and there is no reason to believe that it did not happen then.

I have done a lot of ocean fishing. Even a small tuna can stress to the max modern monofilament line. They are extremely fast and powerful swimmers. A shark is another thing. It requires very strong tackle. Of course a piece of meat on a rope could conceivably work, but it would take a very clever methodology to land it.