That means ancient artists were drawing what they saw around them, and were not abstract or symbolic painters - a topic of much debate among archaeologists - said the findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

By analysing bones and teeth from more than 30 horses in Siberia and Europe dating back as many as 35,000 years, researchers found that six shared a gene associated with a type of leopard spotting seen in modern horses.

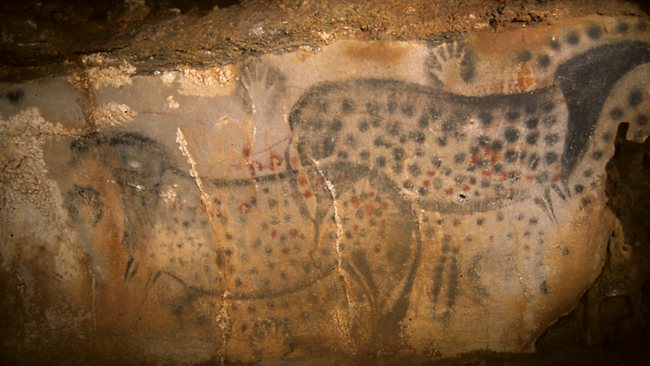

One prominent example that has generated significant debate over its inspiration is the 25,000-year-old painting, The Dappled Horses of Pech-Merle in France, showing white horses with black spots.

"The spotted horses are featured in a frieze which includes hand outlines and abstract patterns of spots," explained Terry O'Connor, a professor at the University of York's Department of Archaeology.

"The juxtaposition of elements has raised the question of whether the spotted pattern is in some way symbolic or abstract, especially since many researchers considered a spotted coat phenotype unlikely for Paleolithic horses," he said.

"However, our research removes the need for any symbolic explanation of the horses. People drew what they saw."

The team was led by Melanie Pruvost of the Department of Evolutionary Genetics at the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research and the Department of Natural Sciences at the German Archaeological Institute in Berlin.

Scientists from Britain, Mexico, the United States, Spain and Russia helped with the genotyping and analysis of the results.

"We are just starting to have the genetic tools to access the appearance of past animals and there are still a lot of question marks and phenotypes for which the genetic process has not yet been described," said Pruvost.

"However, we can already see that this kind of study will greatly improve our knowledge about the past."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter