© redOrbit

On the heels of the Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite's (UARS) splashdown in the Pacific Ocean,

Telegraph reporter Andy Bloxham warned over the weekend that a second satellite is headed for Earth and should re-enter our planet's atmosphere sometime next month.

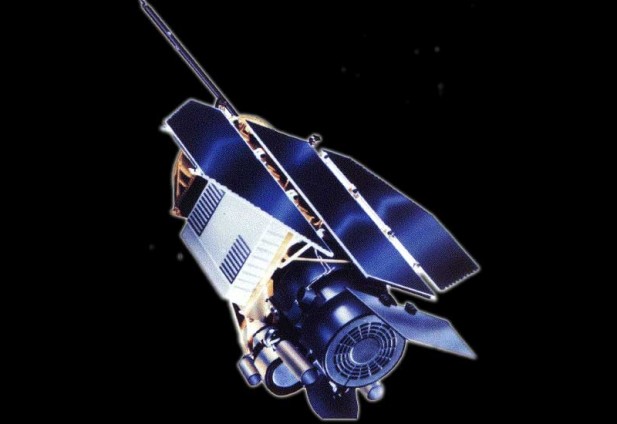

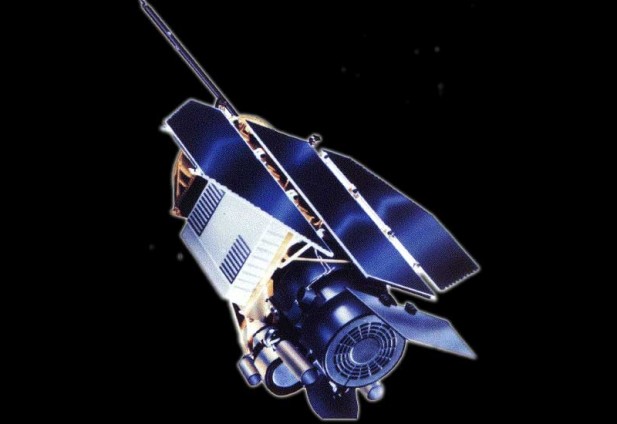

The craft in question is the Röntgensatellit (aka the ROSAT), a 2.4-ton space telescope that was originally constructed by the German Aerospace Center (DLR) and was disabled after its guidance system failed in 1999.

According to Bloxham, authorities originally believed the satellite would burn up completely in Earth's atmosphere, they now believe that pieces of debris from the ROSAT - some weighing upwards of 800 pounds - could collide with the planet's surface by the end of October.

"Up to 30 pieces of metal and carbon fiber are expected to survive the blazing temperatures of re-entry to the Earth's atmosphere and strike land,"

The Telegraph writer said on Saturday. "Among them are the giant mirrors which were designed to be heat-resistant to protect the telescope's x-ray array."

Heiner Klinkrad, the head of the space debris office at the European Space Agency, told Bloxham that the Röntgensatellit had "a large mirror structure that survives high re-entry temperatures."

"ROSAT does not have a propulsion system on board which can be used to maneuver the satellite to allow a controlled re-entry," added Joanne Wheeler, a member of the law firm CMS Cameron McKenna, which represents the UK on the UN Subcommittee for the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space. "The time and position of ROSAT's re-entry cannot be predicted with any precision due to fluctuations in solar activity, which affect atmospheric drag."

ROSAT could well be the second piece of space debris to hit the Earth in a month's time.

Early

Saturday morning, UARS re-entered the planet's atmosphere, and debris from the satellite landed somewhere in the Pacific Ocean between 11:23 p.m. EDT on September 23 and 1:09 a.m. EDT on September 24.

Much of the UARS would have been burned up upon its return, but an estimated 26 pieces no larger than 330 pounds were believed to have survived re-entry. According to NASA officials, the

exact location where the wreckage landed remains unknown.

"Because we don't know where the re-entry point actually was, we don't know where the debris field might be," Nicholas Johnson, chief orbital debris scientist at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston, told Reuters reporter Irene Klotz. "We may never know."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter