They weren't celebrating the Fourth of July. They were waiting for the end of the world.

These happy campers were the followers of a 19th-century version of the Rev. Harold Camping, the Rapture predictor.

The views of the Rapture reverend, broadcast over his multi-million-dollar radio, TV, satellite and website empire, would move those Cincinnatians to say: Been there. Done that.

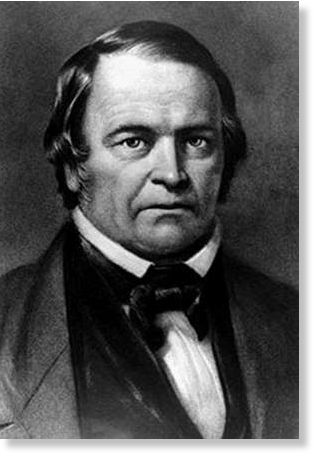

They knew what it was like to fall under the spell of a well-heeled, charismatic preacher. As with Camping, their hells fire and brimstone pastor - the Rev. William Miller - used the latest mass media to gain worldwide attention for his prediction that the world was going to come to an end.

Before the end came, predicted Miller, Jesus Christ would return. He would be accompanied by the sound of trumpets and in the company of winged steeds pulling chariots. At the stroke of midnight, all of the preacher's true believers would ascend to heaven. After that, the world turn be consumed by a giant fireball. The End.

Cue the fireworks.

The only trouble was, they're weren't any fireworks. Not even a spark.

Worldwide campaign

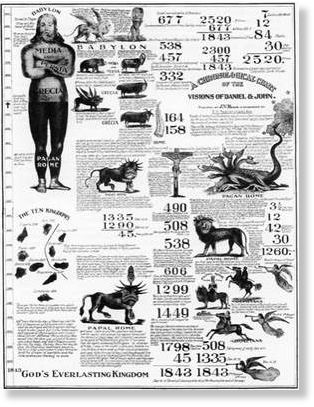

Miller had started peddling his prediction - based on a series of elaborate charts - in the 1820s. By the 1840s, the War of 1812 veteran was spreading the word world-wide.

"What happened this May with Harold Camping," noted Rhys Williams, Sociology Department chairman at Loyola University Chicago, "was small potatoes compared to what went on with William Miller in 1844."

Estimated to be 500,000 strong, Miller's believers carried out his game plan. He used the social networking of his day, speeches, sermons, billboards, posters, tent meetings, books, newsletters and newspapers, to deliver his message. Millerites by the thousands lived in Cincinnati.

On the morning of the appointed day - Oct. 22, 1844 - 2,000 Millerites trekked from downtown Cincinnati. Another 2,500 Millerites stayed behind to pack a temporary tabernacle near where Centennial Plaza stands today in City Hall's shadow.

The tabernacle, naturally, was not made to last. The world was going to come to an end, the Millerites reasoned. No sense putting up something permanent.

The 2,000 faithful followed the path of what is now Central Parkway. At Ravine Street, the Millerites turned right to climb the steep hill.

Some were dressed for the occasion. They wore white ascension robes designed to climb that stairway to heaven.

The Enquirer, then in its third year of existence, reported that some Millerites had quit their jobs. Many got rid of their possessions. They felt the end was near.

At the overlook, some of the chosen ones plopped into adjoining wash tubs, a la the side-by-side bathtubs in the modern-day Cialis ads. Some prayed. Some partied.

They waited for the end. And for Jesus.

Neither arrived. So, Oct. 22, 1844, came to be known as the Great Disappointment.

At dawn, the Millerites retraced their route. Along the way, they were openly ridiculed. The Enquirer called them "deluded fanatics of this most ridiculous humbug."

Miller - based in upstate New York - said: Whoops! My bad. Faulty calculations. (Camping used the same excuse when his Rapture failed to materialize.)

Follower picked date

To be fair, Miller never picked an exact date for his rapture. He hedged his bets by citing a range of dates. A follower selected Oct. 22, 1844. And, Miller didn't object.

Miller - as Camping would 167 years later - became a punchline. Then, as now, the question was asked: Why do people believe this stuff?

"The 1840s were a time of great economic instability, high immigration - people were mad about immigrants taking their jobs - and tumult in religion," said Williams, a former University of Cincinnati professor whose work examines how politics, religion and social movements effect American culture.

"Couple that unsettled world," he added, "with a milieu where people were just influenced by their social circle and the belief in supernatural events does not seem that far-fetched."

Williams paused before adding: "Those conditions sound a lot like today."

Then as now, Americans dealt with these "repent, the end is near" movements with a sense of humor.

As the Great Disappointment dawned near Boston, a trumpet could be heard. The faithful cried: "Hallelujah!"

That was no angel blowing his horn. It was a prankster.

After his second blast on the horn, he called out:

"Go back to your work. Gabriel ain't a-coming."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter