Soon, colleagues would awake to his e-mail, expressing his anguish and shame over the discovery that the tiniest, most vulnerable of all patients - premature babies - had been over-radiated in the department he ran at State University of New York Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn.

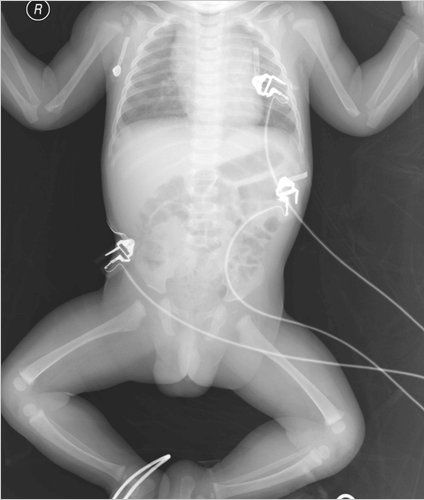

A day earlier, Dr. Sclafani noticed that a newborn had been irradiated from head to toe - with no gonadal shielding - even though only a simple chest X-ray had been ordered.

"I was mortified," he wrote on July 27, 2007. Worse, technologists had given the same baby about 10 of these whole-body X-rays. "Full, unabashed, total irradiation of a neonate," Dr. Sclafani said, adding, "This poor, defenseless baby."

And the problems did not end there. Dr. John Amodio, the hospital's new pediatric radiologist, found that full-body X-rays of premature babies had occurred often, that radiation levels on powerful CT scanners had been set too high for infants, and that babies had been poorly positioned, making it hard for doctors to interpret the images.

The hospital had done the full-body X-rays, known as "babygrams," even though they had been largely discredited because of concerns about the potential harm of radiation on the young. Dr. Sclafani and Dr. Amodio quickly stopped the babygrams and instituted tight controls on how and when radiation was used on babies, according to doctors who work there. But the hospital never reported the problems in the unit to state health officials as required.

A Doctor's E-Mails About Over-Radiated Babies

A little over a week ago, after The New York Times asked about the situation at Downstate, the state health commissioner, Dr. Nirav R. Shah, ordered two offices of the department to investigate.

"Our investigators will pull films, they will examine the medical records and they will interview relevant staff," said Claudia Hutton, the department's director of public affairs. "Our authority to investigate goes basically as far as we need it to go."

The errors at Downstate raise broader questions about the competence, training and oversight of technologists who operate radiological equipment that is becoming increasingly complex and powerful. If technologists could not properly take a simple chest X-ray, how can they be expected to safely operate CT scanners or linear accelerators?

With technologists in many states lightly regulated, or not at all, their own professional group is calling for greater oversight and standards. For 12 years, the American Society of Radiologic Technologists has lobbied Congress to pass a bill that would establish minimum educational and certification requirements, not only for technologists, but also for medical physicists and people in 10 other occupations in medical imaging and radiation therapy.

Yet even with broad bipartisan support, the association said, and the backing of 26 organizations representing more than 500,000 health professionals, Congress has yet to pass what has become known as the CARE bill because, supporters say, it lacks a powerful legislator to champion its cause.

"I would think the public would be outraged that Congress was sitting on what could reduce their radiation exposure," said Dr. Fred Mettler, a radiologist who has investigated and written extensively about radiation accidents.

Individual states decide what standards, if any, radiological workers must meet. Radiation therapists are unregulated in 15 states, imaging technologists in 11 states and medical physicists in 18 states, according to the technologists association. "There are individuals," said Dr. Jerry Reid, executive director of a group that certifies technologists, "who are performing medical imaging and radiation therapy who are not qualified. It is happening right now."

Two months ago, in Michigan - which sets no minimum standards for technologists - the Nuclear Regulatory Commission reported that a large hospital had irradiated the healthy tissue of four cancer patients, three of whom suffered burns, because a technologist repeatedly used the wrong radiological device. "It's amazing to us, knowing the complexity of medical imaging, that there are states that require massage therapists and hairdressers to be licensed, but they have no standards in place for exposing patients to ionizing radiation," said Christine Lung, the technologist association's vice president of government relations.

In New York State, technologists must be licensed and prove that they have passed a professional examination. But there were no continuing education requirements - a provision of the CARE bill - until last year, and regulators usually let hospitals decide whether to discipline technologists. Over the last 10 years, New York health officials say they have not disciplined any of the 20,000 or so licensed technologists for work-related problems.

Children Are Most at Risk

Like many hospitals, SUNY Downstate Medical Center had come to realize that children needed special protection from unnecessary radiation.

Because their cells divide quickly, children are more vulnerable to radiation's effects. And as new ways are found to use radiation in diagnosing and treating injuries and disease, children face an ever-increasing number of radiological procedures. One recent study found that by the age of 18, the average child will have already received more than seven radiological exams.

While the procedures save lives, they are also a source of concern because most scientists believe that the effects of radiation are cumulative - the more radiation a patient receives, the greater the chances of developing cancer. In premature infants, minimizing radiation exposure is especially important because they may require multiple radiological exams for problems like underdeveloped respiratory systems.

In 2007, Dr. Sclafani, the radiology chairman, brought in Dr. Amodio, a highly regarded pediatric radiologist, to oversee diagnostic imaging for children and to evaluate existing practices at Downstate, a large teaching hospital that serves mostly the poor.

Dr. Amodio did not like what he saw. "I have started to compile a list of obvious problems with respect to pediatric images, especially in the neonatal population," he said in a July 26 e-mail to Dr. Sclafani.

A guiding principle for any imaging procedure, regardless of age, is that radiation should be limited - or "coned" - to the area being examined. Yet technologists at Downstate did not always follow that rule. "Improper coning - often entire baby is on radiograph," Dr. Amodio wrote in the first of several bullet points summarizing his findings.

Full-body X-rays of babies are rarely done. "We don't do those anymore," said Dr. Marta Hernanz-Schulman, director of pediatric radiology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. "If I had an image like that, it would most likely have been a stillborn baby."

Dr. Donald Frush, chief of pediatric radiology at the Duke University School of Medicine, said that failing to properly cone, or collimate, the radiation was rare. "The collimation issue is something that technologists are quite aware of and has been emphasized for decades," Dr. Frush said.

Downstate officials did not say how many inappropriate babygrams were taken. In an interview, Dr. Amodio said he did not know why the technologists had failed to protect the infants, but he surmised that because premature babies are especially fragile, technologists might have been afraid to touch them and "do what was really necessary" to administer proper X-rays. "It is a normal human response," he said.

Asked about the case, Dr. David Keys, a board member of the American College of Medical Physics, said, "It takes less than 15 seconds to collimate a baby," adding: "It could be that the techs at Downstate were too busy. It could be that they were just sloppy or maybe they forgot their training."

In his 2007 e-mail, Dr. Amodio said technologists also failed to shield the gonads, a radiosensitive organ. City and state health codes require shielding for young patients, unless it interferes with a diagnosis, which did not appear to be the case at Downstate.

When Dr. Amodio's findings were reported to the hospital's patient safety committee, its chairman, Dr. Eugene M. Edynak, quickly grasped the seriousness of the situation. "Because of the grave nature of these 'findings,' and the need for immediate correction," Dr. Edynak wrote, "I would like Radiology to present these issues at the next Patient Safety Committee." At the same time, Dr. Edynak noted that radiology management had already begun addressing the problems.

Dr. Sclafani was clearly unsettled by the events. "The past two weeks have been among the most troubled of my career," he wrote at the beginning of an expansive e-mail, sent to members of his department at 1:36 a.m. on July 27.

His greatest disappointment was directed at residents and supervisors for not speaking up about the improper X-rays. "Every film, all dictated, and no one brought this to my attention," Dr. Sclafani said.

In another e-mail, he said he felt "alarmed and ashamed" upon seeing poor imaging techniques. "Excessively irradiating children is something we must have zero tolerance about."

Dr. Sclafani recently took a leave from Downstate to do research. But in an interview last year, he said that his department, with Dr. Amodio's help, had made significant changes, not only in reducing the amount of radiation in CT scans for infants as well as adults, but also in reducing unnecessary scans.

In the past, Dr. Sclafani said, manufacturers had marketed CT scanners based on high-quality images, which often meant more radiation. Referring to Dr. Amodio, he said, "What we learned from John is that sometimes the pretty picture is not what we need."

Dr. Amodio described other department changes, including the use of breast shields for girls and, when possible, substituting an ultrasound, which uses no radiation, for CT scans. In addition, he said, he must personally approve all pediatric CT scans.

Downstate officials, after initially answering questions from The Times last year, have declined to answer any more. In a statement, Ronald Najman, a hospital spokesman, said: "We are working with the New York State Department of Health to re-evaluate the issues raised by our Department of Radiology in 2007, and to ensure that we are in compliance with national and state standards."

Push for Continuing Education

Supporters of the proposed CARE legislation say its continuing-education requirement will keep radiological workers abreast of technological changes. If it passes, "certification and licensure will no longer be a one-time event," said Dr. Geoffrey S. Ibbott, former director of the Radiological Physics Center, a federally financed group that tests radiotherapy equipment for accuracy.

A continuing-education provision might have prevented the over-radiation of 76 patients at a hospital in Missouri - a state that does not regulate its radiological workers. The medical physicist there had selected the wrong calibration tool to set up a highly sophisticated linear accelerator.

Ms. Lung, the vice president of the technologists' group, said that while most people knew that radiation could cause cancer and burn holes in patients, "They don't understand that the last person to see that patient, to position that patient, to make sure that procedure is performed safely is the radiological technologist or radiation therapist."

Jerry Reid, executive director of the American Registry of Radiologic Technologists, a group that certifies technologists, said he was optimistic that the proposed legislation, expected to be introduced in March, would finally pass. Congress, he said, "has shown much more interest in this issue over the last year," in the wake of a series of articles in The Times documenting the harm that can result from radiation mistakes.

But even supporters of the bill say much more needs to be done, including making radiological devices safer and requiring that all mistakes be reported to a single national database.

"We still have to address the culture in many radiology and radiation therapy departments where there is reluctance or outright intimidation that prevents people from reporting errors or potential errors," said Dr. Ibbott. "All of our staff must be empowered to identify errors and situations that could lead to errors without fear of retribution."

The American College of Radiology also recommends that all medical radiology units be professionally accredited, yet many are not.

"In my profession, there is very little room for error and no room for unqualified personnel," said Dr. Steve Goetsch, a medical physicist in California who runs training programs in the field.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter