The planned probe of the Alpena-Amberley Ridge - named for the Michigan and Ontario towns that respectively mark the western and eastern ends of the 160-kilometre-long lake bottom feature - is expected to involve remotely operated sonar devices for mapping the underwater terrain, as well as a team of scuba divers to comb the long-submerged landscape in search of spearheads and other signs of hunting activity from the end of the last ice age.

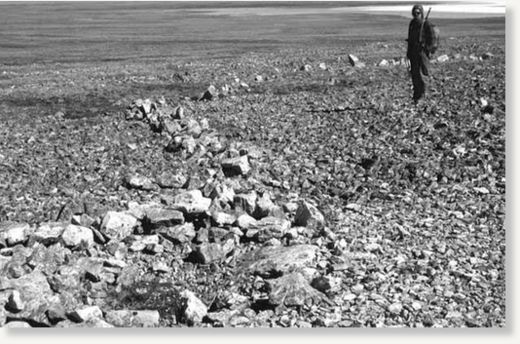

University of Michigan researchers first announced in 2009 that they'd discovered rock formations along the drowned ridge that appeared eerily similar to well-documented caribou-hunting structures used in prehistoric times by the "Paleo-Indian" peoples who once occupied Canada's Arctic and sub-Arctic territories.

Now under about 35 metres of water, the Lake Huron ridge was once a 16-km-wide upland corridor in a lake-dotted landscape that linked caribou wintering grounds in the south to their summer ranges in present-day Northern Ontario and beyond.

"Scientifically, it's important, because the entire ancient landscape has been preserved and has not been modified by farming, or modern development," project leader John O'Shea, a University of Michigan archeologist, said when the rock structures were discovered. "That has implications for ecology, archeology and environmental modelling.''

But after almost 10 millennia at the bottom of Lake Huron, the unusual rock formations found in 2009 constitute "promising" but not definitive evidence of an ancient hunting culture, University of Michigan marine engineer Guy Meadows told Postmedia News on Tuesday. That means scanning the lake floor for more telling traces of a prehistoric human presence, such as fire pits, toolmaking sites and other hunting structures.

Meadows said the Michigan team is working to enlist Canadian researchers - including paleo-environment specialist Lisa Sonnenburg from McMaster University in Hamilton - to help profile the corridor on both sides of the border since "the ridge is half in our country and half in yours."

Meadows and O'Shea have also teamed with Wayne State University computer scientist Robert Reynolds to create a three-dimensional virtual model of the ridge - complete with animated caribou moving along the corridor - to help identify as many "high-probability" targets as possible for this year's archeological investigation.

Based on geological data that gives a general picture of the topography along the ridge 10,000 years ago, the simulation is allowing the experts to "step into that world" and visualize the paths caribou would likely have taken during their mass migrations, Reynolds said in an interview.

The simulation, he added, should also help the team plot where ancient hunters would have established staging grounds and positioned themselves around kills sites to maximize their harvesting chances.

"We really want to produce an artifact, and not just these rock structures that look very promising," said Meadows. "But the area is obviously enormous - it's a proverbial needle-in-a-haystack problem. So if we can use the simulation to guide us as to both where the caribou would have been and what sort of terrain the ancient hunters would have used, we can narrow this search down tremendously."

He and Reynolds said the team is even working toward the development of a computer game that could tabulate the hunting strategies of thousands of online players to further pinpoint the most probable locations ancient hunters would have chosen for kill sites. That development, in turn, would allow players to "participate in an ancient environment," Reynolds noted, and to "move around in the landscape and place different hunting structures in different places in order to survive."

Source: Postmedia News

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter