|

| ©USGS |

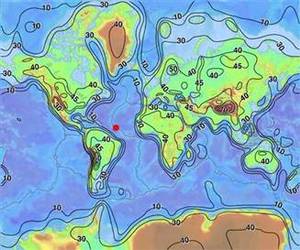

| A map showing the average crust thickness on the Earth. The red dot marks the location of the exposed mantle that scientists aboard the RSS James Cook will study. |

There's a huge hole that extends over thousands of square miles in the Atlantic seafloor between the Cape Verdes Islands and the Caribbean nearly 2 miles below the ocean surface where Earth's deep interior is exposed without any crust covering and a team of scientists wants to find out why.

"It's quite a substantial area," said Chris MacLeod, a marine geologist at Cardiff University in the UK, who will be part of the expedition.

The team of researchers, led by Roger Searle of Durham University, will begin traveling to the site on March 5 aboard the new UK research ship "RSS James Cook." During the course of about six weeks, the team will use sonar to image the seafloor and a robotic seabed drill to collect rock cores.

Earth's crust is constantly being destroyed and created, and this cycle of destruction and renewal occurs faster with ocean crust than with continental crust. New ocean floor crust forms at seams on the Earth's surface, called mid-oceanic ridges, where the planet's tectonic plates meet and where molten magma rises up from the planet's upper mantle.

The upwelling drives seafloor spreading, which is the movement of two oceanic plates away from each other. Oceanic crust is destroyed at so-called subduction zones where two plates collide and typically the denser one slips beneath another plate.

This is how scientists think it works, but areas of exposed mantle on the Earth's surface aren't easily explained by this theory. They are regions "where this process seems to have gone wrong somehow," MacLeod said. "There's no crust formed, and instead we've got mantle -- which is normally in the deep Earth -- on the seafloor."

There are two popular theories about how these holes in the Earth's crust form.

"One is that the original volcanic crust did form but that it's been ripped away by a huge rupture," MacLeod told LiveScience.

MacLeod likens this process to stretching a person's skin until it ruptures, exposing the flesh underneath.

"You take the crust and you stretch it and you pull it and pull it until it breaks," he explained.

The other idea purports that somehow the area of exposed mantle was never covered by a magma crust in the first place.

Regardless of how they formed, the exposed mantle provides scientists with a rare opportunity to study the Earth's rocky innards. Many attempts to drill deep into the planet barely get past the crust.

"One of our objectives now that we've got direct access to these mantle rocks is to try and look at their internal properties and try to find out about the deep Earth process that we can't get at directly," MacLeod said in a telephone interview.

Getting equipment down onto the seafloor where the exposed mantle is will be difficult, however.

"It's a very hazardous, very unforgiving environment," he said. "There are very steep slopes and huge pressures. So getting samples back from these areas is challenging still."

Comment: And then, there is the possibility of cometary impact...