OF THE

TIMES

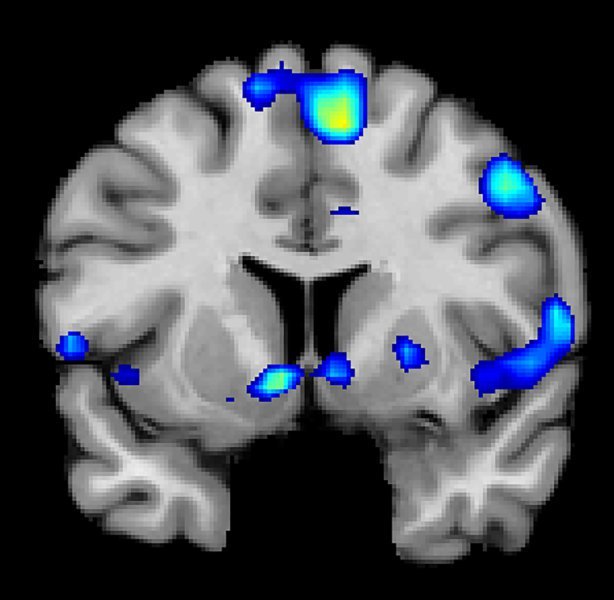

Those cycles - which happen in seconds or fractions of seconds - weren't as visible in the awake brain because the wave doesn't propagate much beyond that column of neurons, unlike during sleep when the wave spreads across almost the entire brain and is easy to detect.During an on state the neurons all start firing rapidly. Then all of a sudden they just switch to a low firing rate. This on and off switching is happening all the time, as if the neurons are flipping a coin to decide if they are going to be on or off.

We observe more alterocentric ['other'-centered], unselfish attitudes expressed by readiness to help; we observe more consistent sensitivity towards the needs of others forsaking primitive selfishness. This attitude is characterized by more or less strong participation of thoughtfulness and reflection. This is empathy. ... Typical examples are: a tendency to defend others, a heart‑warming attitude, understanding, and the like, which are accompanied by reflection and critical evaluation. (Dabrowski, 1970, Mental Growth Through Positive Disintegration)

Comment: Related reading: