© Yulliii/Shutterstock

When the Neanderthal genome was

first sequenced in 2010 and compared with ours, scientists noticed that genes from

Homo neanderthalensis also showed up in our own DNA. The conclusion was inescapable: Our ancestors mated and reproduced with another lineage of now-extinct humans who live on today in our genes.

When the

Denisovan genome was sequenced soon after, in 2012, it revealed similar instances of interbreeding. We now know that small populations from all three

Homo lineages mixed and mingled at various times. The result is that our DNA today is speckled with contributions from ancient hominin groups who lived alongside us, but did not survive to the present day. Genes from Denisovans and Neanderthals are not present in everyone's DNA - for example, some Africans have neither, while Europeans have just Neanderthal genes. But, these genetic echoes are loud enough to stand out clearly to scientists.

On one level, it's not shocking that DNA from other human groups resides within us.

H. sapiens today is the result of

millions of years of evolution; we can count numerous species of ancient hominin among our ancestors. But the Neanderthal and Denisovan contributions to our genetic makeup happened far more recently, after

H. sapiens had already split from other human groups. Those interbreeding events, also called introgressions, did not create a new species of human - they enriched an already existing one. Some of the traits we acquired are still relevant to our lives today.

"There's a lot of evidence for some type of introgression from ancient hominins into modern humans, particularly modern humans out of Africa," says Adam Siepel, a computational biologists at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. "I don't think there's any real question among experts in the field as to whether the evidence overwhelmingly supports that event."

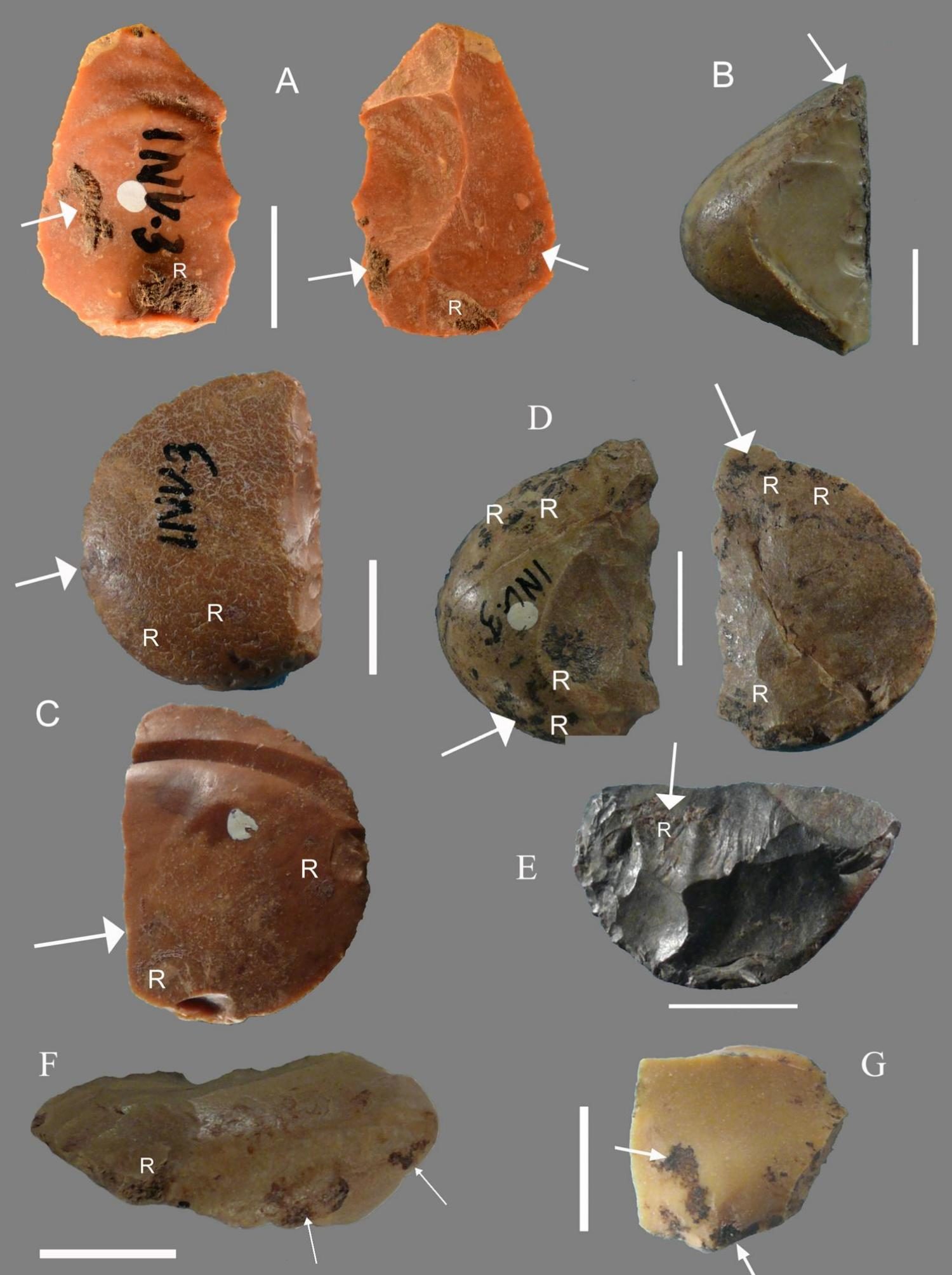

© Thilo Parg/Wikimedia CommonsReplica of a Denisovan finger bone fragment, originally found in Denisova Cave in 2008, at the Museum of Natural Sciences in Brussels, Belgium.

Some evidence also suggests that there may be more than

two additional human groups lurking in our DNA, what researchers sometimes call "ghost lineages." Modern humans living in Africa may have interbred with one or more hominin species there, resulting in even more addition to our current DNA. And a recent study of modern-day Indonesians suggests that what we call Denisovans was actually three separate groups of hominins, at least one of which can be thought of as its own species. The ancestors of Asians and Melanesians mated with at least one of these groups, and possibly more.

Comment: Regarding the druids, in Where Troy Once Stood: The Mystery of Homer's Iliad & Odyssey Revealed Laura Knight-Jadczyk writes: See also: