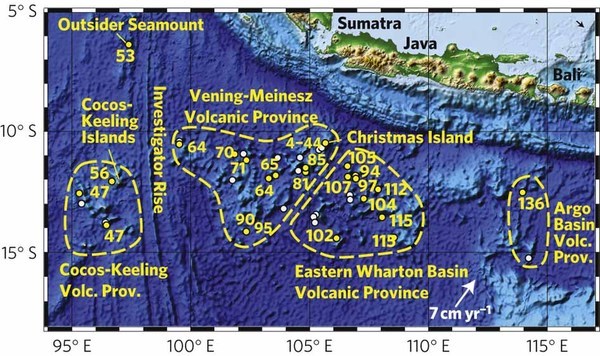

© Nature Geoscience/Hoernle, et al. A map of the Christmas Island Seamount Province with seamount locations and plate motions.

If you ever find yourself on a leisurely submarine ride through the northeastern Indian Ocean, be on the lookout for some amazing views: more than 50 large seamounts, or underwater mountains, dot the ocean floor, some rising as high as 3 miles (4,500 meters).

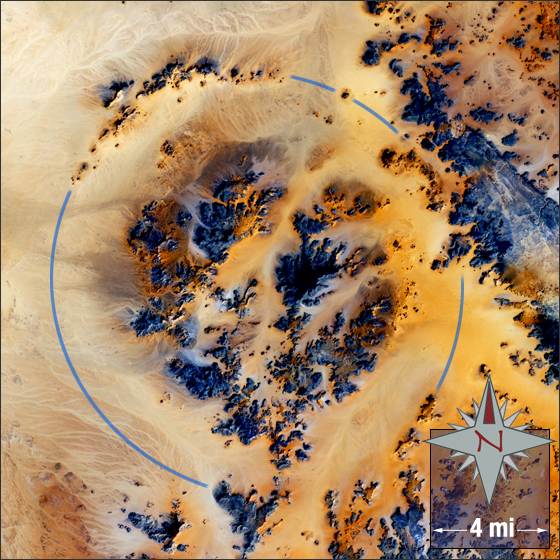

The Christmas Island Seamount Province, as the area is known, spans a 417,000-square-mile (1 million square kilometers) swath of seafloor.

Just how the massive underwater structures got there has been up for debate, but some new geochemical detective work may have solved the mystery.

The seamounts are made of recycled rocks from the

ancient supercontinent of Gondwana, said geochemist Kaj Hoernle of the University of Kiel in Germany. Their turbulent geological history explains the massive size and puzzling placement of these features.

Ubiquitous and mysteriousTens of thousands of seamounts line the floors of

the world's oceans, but exactly how most of these formed is unclear.

Some, like the Hawaiian - Emperor seamount chain that extends northwest from the Hawaiian Islands,

formed over hotspots in the mantle, just as the islands themselves did. Other seamount chains were created when tectonic plate boundaries and other fractures in the ocean crust allowed lava to escape and harden at the surface.

But the Christmas Island Seamount Province doesn't fit either of these models, Hoernle said. The structures are too widespread and diffuse to have formed over a single hotspot; they're also aligned perpendicularly along breaks in the ocean crust, which means they didn't form above a fracture.

"We knew they were volcanic," Hoernle told OurAmazingPlanet, "but beyond that, it was more or less a mystery."