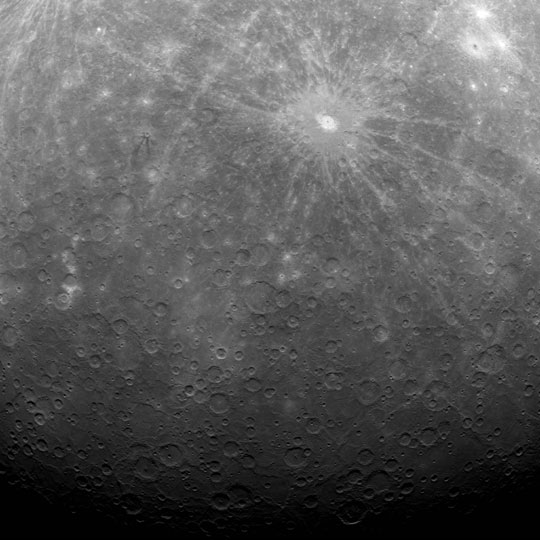

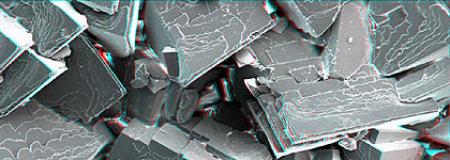

Eventually, the tug of gravity from a passing star slowed it down ever so slightly, and that was enough to send it plummeting back toward the Sun, into the region where it had formed billions of years earlier. By a great quirk of irony Jupiter was again in its path. This time, the planet's gravity captured it into a long, elliptical orbit. On July 7, 1992, it executed a cosmic hole-in-one, passing through Jupiter's slender ring and breaking apart under the planet's ripping tides.

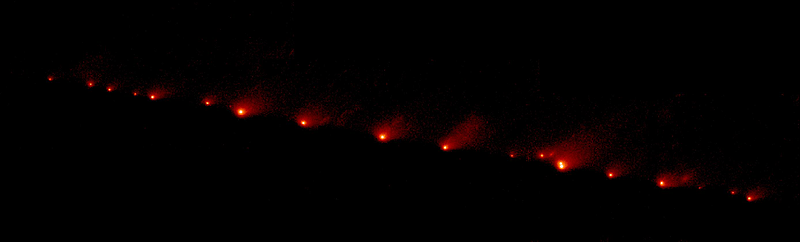

On the night of March 24, 1993, astronomers Eugene and Carolyn Shoemaker and David Levy were searching the skies when they noted an oddly shaped blotch near Jupiter. It was a comet to be sure, but quite unusual in shape. The next morning it became known as Shoemaker-Levy 9, or SL9 for short. With additional detections, its prior history as a body disrupted by Jupiter became clear. As new data accumulated, however, SL9 became even more remarkable, because astronomers realized that it had evaded Jupiter for the last time. In July 1994, the world watched as the broken fragments of SL9 plunged into Jupiter one by one. Few comets are ever featured on the front page of the New York Times, but the July 19 headline read, "Earth-Sized Storm and Fireballs Shake Jupiter as a Comet Dies." SL9 went out with a bang. The impacts left behind blotches in Jupiter's clouds but, after a few months, they faded away. End of story.

Or so we thought. As we have just published in the journal Science Express, this story has an unexpected epilogue.