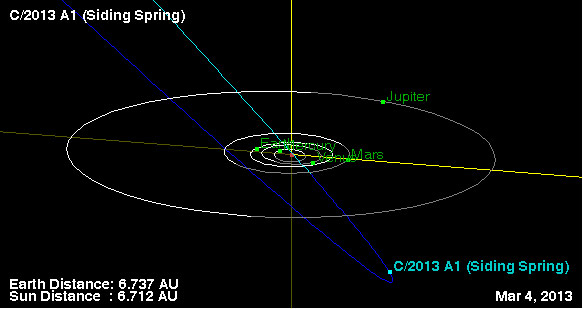

For the first time, astronomers have managed to measure the rate of spin of a supermassive black hole - and it's been clocked at 84 percent of the speed of light, or the maximum allowed by the law of physics.

"The most exciting part of this finding is the ability to test the theory of general relativity in such an extreme regime, where the gravitational field is huge, and the properties of space-time around it are completely different from the standard Newtonian case," said lead author Guido Risaliti, of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) and INAF-Arcetri Observatory in Italy.

Notorious for ripping apart and swallowing stars, supermassive black holes live at the center of most galaxies, including our own Milky Way.

They can pack the gravitational punch of many million or even billions of suns - distorting space-time in the region around them, not even letting light escape their clutches.