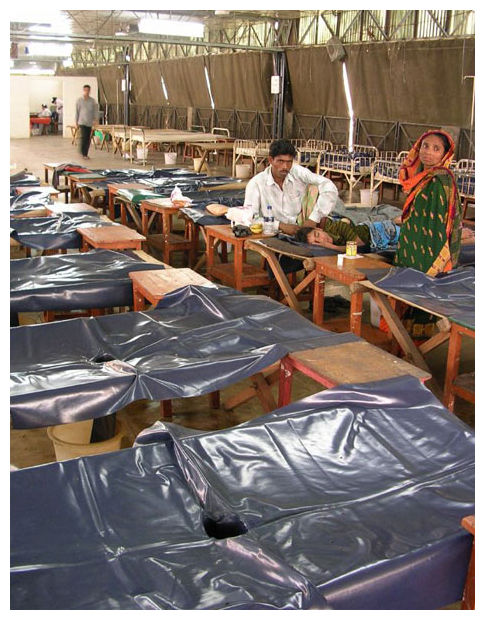

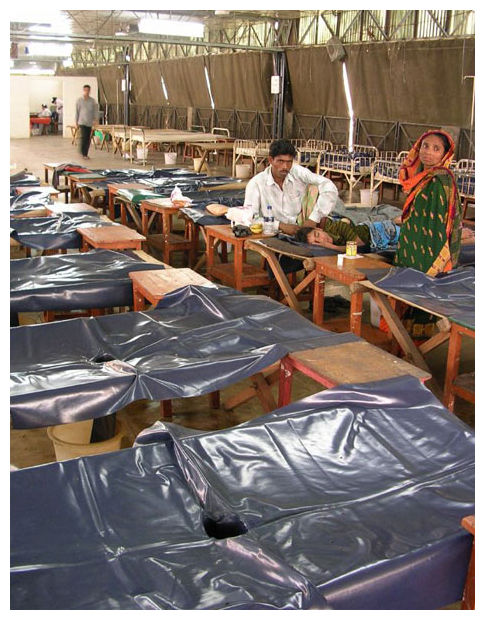

© Mark Knobil/Creative CommonsLaid low. A cholera ward in Dhaka, Bangladesh, a country where nearly half the people are infected with the cholera bacterium by age 15.

Cholera kills thousands of people a year, but a new study suggests that the human body is fighting back. Researchers have found evidence that the genomes of people in Bangladesh - where the disease is prevalent - have developed ways to combat the disease, a dramatic case of human evolution happening in modern times.

Cholera has hitchhiked around the globe, even

entering Haiti with UN peacekeepers in 2010, but the disease's heartland is the Ganges River Delta of India and Bangladesh. It has been killing people there for more than a thousand years. By the time they are 15 years old, half of the children in Bangladesh have been infected with the cholera-causing bacterium, which spreads in contaminated water and food. The microbe can cause torrential diarrhea, and, without treatment, "it can kill you in a matter of hours," says Elinor Karlsson, a computational

geneticist at Harvard and co-author of the new study.

The fact that cholera has been around so long, and that it kills children - thus altering the gene pool of a population - led the researchers to suspect that it was exerting evolutionary pressure on the people in the region, as malaria has been shown to do in Africa.

Another hint that the microbe drives human evolution, notes Regina LaRocque, a study co-author and infectious disease specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, is that many people suffer mild symptoms or don't get sick at all, suggesting that they have adaptations to counter the bacterium.

To tease out the disease's evolutionary impact, Karlsson, LaRocque, and their colleagues, including scientists from the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research in Bangladesh, used a new statistical technique that pinpoints sections of the genome that are under the influence of natural selection. The researchers analyzed DNA from 36 Bangladeshi families and compared it to the genomes of people from northwestern Europe, West Africa, and eastern Asia.

Natural selection has left its mark on 305 regions in the genome of the subjects from Bangladesh, the team reveals online today in

Science Translational Medicine.