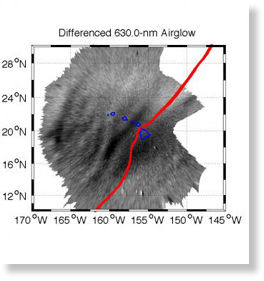

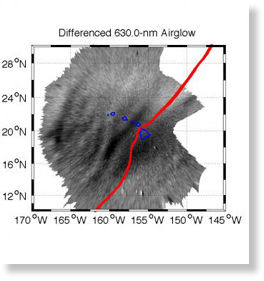

© UnknownAirglow waves captured by the Illinois imaging system over Hawaii. The red line represents the location of the ocean-level tsunami at the time of the image.

Researchers from Brazil, France and the United States, using a highly sensitive, wide-angle camera at the top of Haleakala volcano in Hawaii, detected the 'airglow' signature in the atmosphere of the 11 March tsunami that devastated Japan, demonstrating that the genesis of a tsunami leaves a fingerprint in the ionosphere - an ionised zone of the atmosphere more than 80 kilometres up.

Tsunamis usually cause the sea level to rise rapidly by a few centimetres, which displaces the air immediately above it. This creates waves in the air that move quickly upward, eventually reaching and disturbing the ionosphere. Interaction with the charged ionosphere creates a faint red glow, the signature airglow that can be detected.

This effect was predicted in the 1970s, but little progress has been made since then on using these observation methods. The researchers presented their observations in a paper in

Geophysical Research Letters last month (7 July).

"We have been studying the ionosphere since 1999, but we didn't expect to end up with a new method for tsunami detection," Jonathan Makela, an electrical engineer at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, United States, and the lead author of the paper, told SciDev.Net.