© NASA, G. Verschuur

Seeing is believing, except when you don't believe what you see.

This is according to veteran radio astronomer Gerrit Verschuur, of the University of Memphis, who has an outrageously unorthodox theory that if true, would turn modern cosmology upside down.

He proposes that at least some of the fine structure seen in the

all-sky plot of the universe's cosmic microwave background is really the imprint of our local interstellar neighborhood. It has

nothing to do with how the universe looked 380,000 years after the Big Bang, but how nearby clouds of cold hydrogen looked a few hundred years ago.

The idea is so unbelievable that it's little wonder that cosmologists have largely ignored his work that has been published over the last few years.

"Science is supposed to be about the excitement of making new discoveries. But this discovery terrifies me," he told reporters at the recent meeting of the

American Astronomical Society in Anchorage, Alaska.

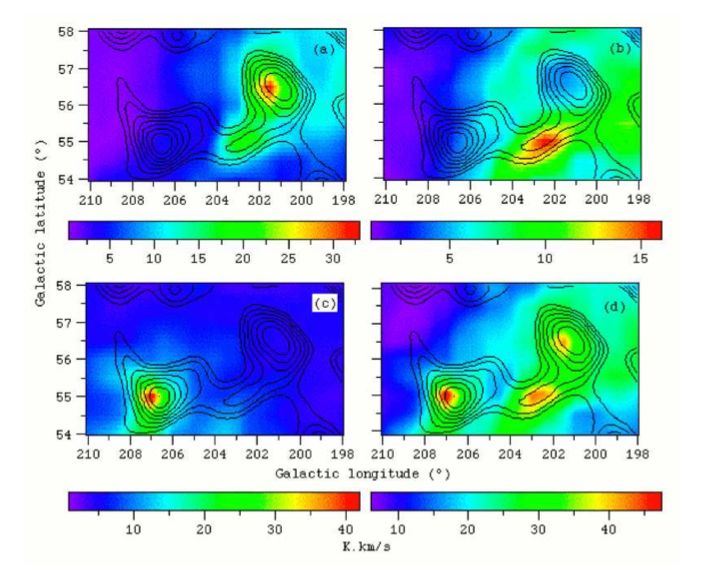

Verschuur's radio maps of hydrogen surrounding our local stellar neighborhood out to a few hundred light-years appear to have an uncanny match-up to the mottled structure of the cosmic microwave background that is 13.7 billion light-years away.

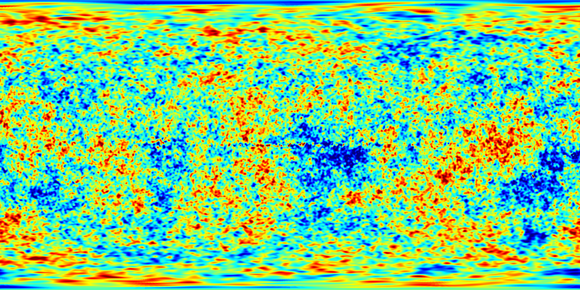

NASA's Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) mapped the CMB in exquisite detail in 2003. The data show the slight temperature fluctuations in the early universe that are believed to be the seeds of galaxy formation. It is a landmark observation that is considered the "blueprint" for the subsequent evolution of the universe.

Verschuur is quick to applaud the WMAP team for a "brilliant experiment" to attempt to resolve the structure of the primeval universe as encoded in ancient microwave radiation. But he suggests that the team failed to subtract all the foreground radio phenomena that may have contaminated the data.

© NASA, G. Verschuur

In a moment of serendipity, Verschuur found that his contour radio maps of cold hydrogen in interstellar space seem to fit the false-color speckled microwave background pattern (shown above). It's like a child putting a puzzle piece into a pre-shaped slot.

Peaks in the foreground radio emission appear to overlay the peaks in the warmest region of the background, or appeared slightly offset.

In 2007 and 2010, Verschuur

published a list of over 100 apparent matches between the CMB pattern and his interstellar hydrogen pattern.

Verschuur would have dismissed this as an odd coincidence until he realized that small interstellar clouds of hydrogen collide and jostle electrons to generate high-frequency radio emissions.

Like other foreground sources this would overlay the CMB. Because the WMAP team didn't consider or know about the contribution of such a phenomenon they didn't try and subtract it as they did numerous other electromagnetic "contaminants" in their data reduction, says Verschuur.

If Verschuur's theory is correct, the consequences would send seismic waves through the cosmology community. It implies that at least some of the small-scale structure in the CMB map doesn't exist at all.

But hold on. Detailed analysis of the angular diameter of CMB blobs yield a

power spectrum that exactly fits theoretical predictions. The first peak in the spectrum shows a geometrically flat universe. The next peak determines the density of normal matter. The third peak provides information about the density of dark matter. And it all fits together beautifully.

Verschuur shrugs off the interpretation, saying that astronomers can analyzed the data and then stop when, "they find what they are looking for.

© NASA, G. Verschuur

Cosmologists have also said that Verschuur's claim needs a detailed statistical analysis. But Verschuur is equally dismissive: "astronomers who study interstellar structure do not use statistics to show associations between different forms of matter ... they go by what the data look like."

Astrophysicists Kate Land and Anze Slosar conducted an analysis of Verschuur's study that was published in the Dec. 10, 2007, edition of The Astrophysical Journal.

In an email to Wired, they concluded that Verschuur's correlation of the radio emissions from nearby hydrogen and the WMAP data was nothing more than a coincidence.

"Notoriously, by eye, one can often think they see correlations between patterns," Land told Wired. "But one doesn't really see the anti-correlations. So two maps (of the sky) that just fluctuate randomly can appear correlated."

This wouldn't be the first time that random fluctuations in the CMB have led researchers to claim that they have seen patterns,

only for their claims to be refuted and found flawed.

Observations from the European Space Agency's Planck mission that is now measuring the CMB promises to yield a more detailed all-sky map than WMAP. Assuming the datasets between the missions agree at some level, this would rule out Verschuur's claim as simply being an over-interpretation of his radio observations -- agreeing with Land's 2007 rebuttal.

However, if Verschuur is right, WMAP cosmologists might not have seen the forest for the trees.

"The idea is so unbelievable that it's little wonder that cosmologists have largely ignored his work that has been published over the last few years."

It's only unbelievable to the scientific priesthood, who demand obeisance to their Big Bang theory.