© machinewrench.com

The World War II generation may have passed down to their grandchildren the effects of chemical exposure in the 1940s, possibly explaining current rates of obesity, autism and mental illness, according to one researcher.

David Crews, professor of psychology and zoology at the University of Texas at Austin,

theorized that the rise in these diseases may be linked to environmental effects passed on through generations. His research showed that descendants of rats exposed to a crop fungicide were less sociable, more obese and more anxious than offspring of the unexposed.

The results, published today in the

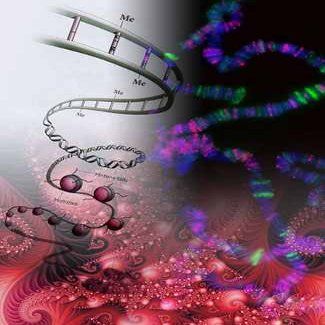

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, are part of a growing field of study that suggests environmental damage to cells can cause inherited changes and susceptibility to disease. Crews said his findings are applicable to humans.

"This, I think, is the first causal demonstration that environmental contamination may be the root cause of the great increase in obesity and the great increase in mental disorders," Crews said in a telephone interview. "It's as if the exposure three generations before has reprogrammed the brain so it responds in a different way to a life challenge."

In the study, a group of rats were exposed once to vinclozolin, a common fungicide used to protect fruits and vegetables. This single contact altered how their genes were activated, and future generations also carried this change, though they never had been exposed to the chemical, Crews said.

Stress ReactionsWhen these descendants were then restrained as adolescents, causing stress, their reactions differed from relatives of unexposed rats. The affected rats also showed less interest in new companions and spent more time in the corners of an open field rather than the middle than rats whose ancestors weren't exposed. Rats related to the exposed animals that weren't stressed were obese, Crews said.

Crews tested the reactions of rats three generations after exposure because humans are that far removed from the debut of new chemicals seven decades ago, he said.

During the 1940s, powerful agricultural chemicals including DDT, the first synthetic pesticide, and new types of plastics were introduced."The chemical revolution started in the 1940s, with World War II and the development of organic chemistry, plastics, detergents, fertilizers," Crews said.

Andrew Feinberg, director of Johns Hopkins University's Epigenetics Center in Baltimore, said Crew's theory may be premature, after reading the paper.

Evidence 'Not Clear'"We should be very careful about overstating what looks like basic science with public health implications," Feinberg said in an interview. "Currently we don't have enough evidence showing that these fungicides are causing common human disease through an epigenetic mechanism. It's research that's well worth doing, but it's clear that that hasn't been shown."

Other studies in epigenetics, a field that investigates the inheritance of cellular changes outside the realm of DNA, have shown chemical exposure can affect fertility. A project by researchers at Washington State University published in

PLoS One in February found that when pregnant rats are injected with common environmental toxins, such as chemicals used in insect repellents, plastics and jet fuel, offspring for three generations have reproductive problems.

Japanese scientists are studying whether descendants of atomic bomb survivors have inherited epigenetic changes that make them more susceptible to cancer and heart disease.

"Diseases like autism, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder are not single gene, or even a few genes, they're complex of genes," Crews said. "It also turns out a lot of these genes that we have identified are epigenetically modified."

--Editors: Angela Zimm, Andrew Pollack

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter