Antibiotic resistance is often seen as a modern phenomenon - an ability generated by bacteria in order to defend against the challenges of modern medicine. This is supported by the fact that bacteria from before the era of antibiotics are often more susceptible to their use. Which is why I found it intriguing that recent studies (ref below) have unearthed bacteria from 30 000-year old permafrost sediment and have found evidence of genes that provide resistance against three of the most common types of antibiotics used in hospitals:

β-lactam,

tetracycline and

glycopeptide antibiotics.

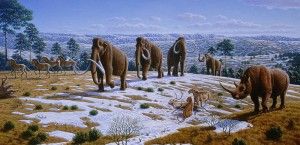

As every microbiologist knows, a good way to get bacteria to stay in an unchanged state is to freeze them. Digging down beneath the surface in areas such as Dawson City in Yukon, Canada reveals layers that have remained frozen since the ice-age and contain, among all the mammoths and toothy-tigers, frozen and uncontamined samples of bacteria.

The researchers focused on

Actinobacteria; a soil bacteria with many strains still around in modern times. As a soil bacteria, modern

Actinobacteria carries a whole arsenal of antibiotic and antifungal agents in order to protect itself in the cut-throat world of soil microbiotica. The researchers were looking to see what kind of antibiotic substances this ancient bacteria would have.

To do this they carried out a set of PCR reactions. These worked by amplifying any sequences of tetracyclin, vancomycin and B-lactam resistance. To the researchers' surprise, all of these genes were present in the ancient bacteria. What's more the vancomycin resistance genes (which were first discovered in bacteria in the late 1980s!) were remarkably similar to the modern ones.

Why is the resistance there? Around thirty thousand years before the NHS the gene that would go on to make

Staphylococcus aureus even more unbeatable was hanging around in the permafrost. The paper doesn't really go into that but I think a good contender for the answer is that while people might not be using antibiotics, other bacteria certainly are. A lot of antibiotics are extracted from soil bacteria in the first place, which use them to defend their living spaces and protect themselves against predatory bacteria or fungi.

I suspect that back in the permafrost days, antibiotics would be exist almost exclusively in soil bacteria. For any bacteria not in this environment antibiotics aren't much more than an unnecessary load on the genome. Nowadays, however, by strongly selecting for any bacteria that carry resistance, humans have helped those genes to spread out of soil bacteria and into more pathogenic strains.

Bacteria have been fighting each other with antibiotics for millions of years. It's only recently we've begun to steal their weapons.

-

D'Costa VM, King CE, Kalan L, Morar M, Sung WW, Schwarz C, Froese D, Zazula G, Calmels F, Debruyne R, Golding GB, Poinar HN, & Wright GD (2011). Antibiotic resistance is ancient. Nature PMID:

21881561About the Author: A biochemist with a love of microbiology, the Lab Rat enjoys exploring, reading about and writing about bacteria. Having finally managed to tear herself away from university, she now works for a small company in Cambridge where she turns data into manageable words and awesome graphs. Follow on Twitter

@labratting.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter