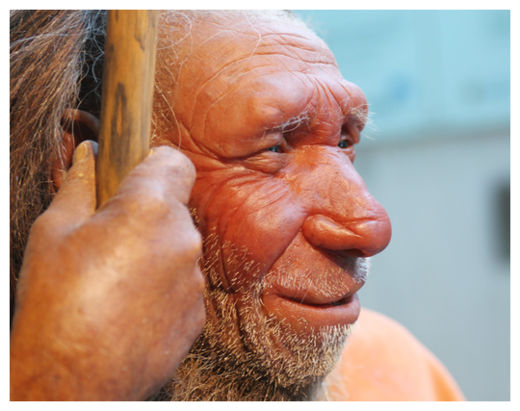

© CorbisA lifelike model of a Neanderthal at the Neanderthal Museum in Mettmann, Germany.

Neanderthals in Western Europe started disappearing long before Homo sapiens showed up, suggesting that cold weather, and not cold-hearted humans, might have been responsible for the species' ultimate demise.

The findings, published in the journal

Molecular Biology and Evolution, suggest that at least one population of Neanderthals was vulnerable to climate change.

Love Dalén, lead author of the paper, told Discovery News that "even if the Neanderthals were capable of surviving periods of extreme cold, the game species they relied on likely could not, so their resource base would have been severely depleted."

Neanderthals appear to have favored hunting wooly mammoths and other big game. Neanderthals were also big-brained, with the ability to make stone tools, construct garments, control fire and find shelter.

For the study, Dalén of the Swedish Museum of Natural History and his colleagues analyzed mitochondrial DNA sequences from 13 Neanderthal individuals, including a new sequence from the site of Valdegoba cave in northern Spain.

The researchers found that Neanderthals from Western Europe, Asia and the Middle East that were older than 50,000 years showed a high degree of genetic variation, on par with what might be expected from a species that had been abundant in those areas for a long period of time.

But Neanderthals from Western Europe younger than 50,000 years ago showed an extremely reduced amount of genetic variation. The scientists believe this means the earlier population of Neanderthals there was dwindling.

"We argue that Neanderthals disappeared in Western Europe for a period of time," co-author Rolf Quam, a Binghamton University anthropologist, told Discovery News.

"Subsequently, the region was re-occupied by individuals from a surrounding region," Quam added. "It is not possible, based on the current genetic data, to determine the geographic region of this new source population."

The scientists suspect that climatic conditions were not as extreme in the surrounding areas at the time, so that Neanderthals were able to move back into Western Europe. At present, there is no clear evidence of

Homo sapiens being in Europe earlier than about 35,000 to 40,000 years ago, according to Quam -- so it seems humans did not play a role in the early Neanderthal population's demise.

The latest findings may shed light on what ultimately happened to Neanderthals.

"The fate of the Neanderthals is one of the greatest mysteries in paleoanthropology," co-author Anders Götherström said. "Two main hypotheses center on climatic factors and competition with modern humans. The results of our study suggest Neanderthals were susceptible to harsh climatic conditions, independently of whether modern humans were present or not."

The last Ice Age could therefore have wiped Neanderthals out.

Still, others believe Neanderthals were simply absorbed into the modern human populations due to the

two groups mating.Julien Riel-Salvatore of the University of Colorado Denver worked on another recent Neanderthal study. He shared that "sequencing of ancient Neanderthal DNA indicates that Neanderthal genes make up from 1 to 4 percent of the genome of modern populations -- especially those of European descent. While they disappeared as a distinctive form of humanity, they live on in our genes."

The Neanderthals are still with us ! They did not "die out" like the jews would have you believe !!!

[Link]