OF THE

TIMES

A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual doom.

I thought the financial destruction of the collective west is the goal of the globalist elitists.

Post-capitalism is not the new feudalism. Feudalism is a person who comes and says, “In the early stages, your body belongs to me, but not as a...

And sometimes they ask me: "But how are new elites created?" When the crisis reaches its peak, new elites emerge with bloodshed. Then new...

Québec is choking on ignorants & pretentious civil servant red-tapers. (Sounds like worms don't it -- they ARE!!) Ottawa is choking on fakes...

Something else.... What are the new rulers of the world preparing for us?the dying roar of the departing class Author: Andrei Fursov There is a...

To submit an article for publication, see our Submission Guidelines

Reader comments do not necessarily reflect the views of the volunteers, editors, and directors of SOTT.net or the Quantum Future Group.

Some icons on this site were created by: Afterglow, Aha-Soft, AntialiasFactory, artdesigner.lv, Artura, DailyOverview, Everaldo, GraphicsFuel, IconFactory, Iconka, IconShock, Icons-Land, i-love-icons, KDE-look.org, Klukeart, mugenb16, Map Icons Collection, PetshopBoxStudio, VisualPharm, wbeiruti, WebIconset

Powered by PikaJS 🐁 and In·Site

Original content © 2002-2024 by Sott.net/Signs of the Times. See: FAIR USE NOTICE

... Note the words used in this article such as "likely," "possibly," these words are the mantra for modern day researchers for the lack of clear information and shows their grand delusion of truth. The basic assumption researchers have made is erroneous and having done that they are trying to fit everything to suit their erroneous assumption. If we start with the assumed reality that 2+2 = 5 then our whole arithmetic, no matter how impressive it is, is going to be wrong in finally. How can a computer model designed today show me what were the conditions thousands of years ago. This is absolute foolishness. They cannot even have a computer model to show me what happened in Uganda last week !!!

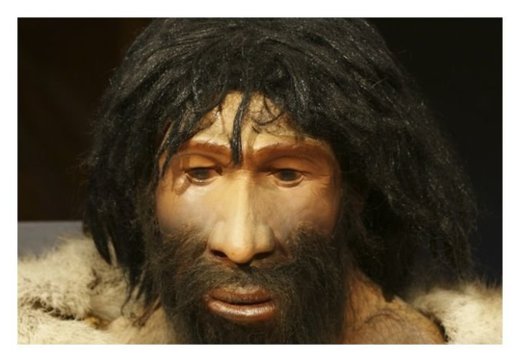

The assumption made by scientists in this case, for the lack of any better proof is that Humans evolved from Neanderthals. Where is the proof of this? They say evolution takes millions of years of gradual change so where is the fossil evidence of 100% Neanderthal leading to a gradual 90% Neanderthal-10% human mix, which should at some time lead to 50% Neanderthal-50% human mix, and gradually 10% Neanderthal-90% human mix, and finally a 100% pure human. This is what I would consider as absolute proof. Not some vague assumption and guess work or speculation.

If you really go looking for hints of genetic similarities, you will see that we also have fish gene as we both have eyes and blood. Science should mean Perfection. No room for guess work and speculation as is the case here.

Sad that the very faith that researchers denounce of religionists of adhering to, is exactly what they demand of their modern day blind followers. Modern day scientists are mostly a few corrupt megalomaniacs hungry for power, recognition and awards - not to mention, they have also claimed the position of God in society, a society as a result that is in absolute misery with no one healthy, happy, fulfilled or satisfied.