In the whodunit-style search for the culprit behind drastic sea level rise many thousands of years ago, new research may have cleared one falsely accused party - but, like any good thriller, the story of the exoneration brings with it an ominous twist, and one that has implications for life on Earth today.

The last time portions of the Earth were as warm as they are today was around 100,000 years ago. Over a span of 12 toasty millennia known as the Last Interglacial Period (128,000 to 116,000 years ago), summertime temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere were as much as 9 degrees Fahrenheit (5 degrees Celsius) hotter, and worldwide, sea levels were roughly 21 feet (6.5 meters) higher than they are now.

"The only ways of doing that are thermal expansion of the oceans, and melting of ice," said Anders Carlson, an assistant professor in the department of geosciences at the University of Wisconsin and author of a paper on the ancient sea level rise published today in the journal Science.

"Seas rise over millions of years, driven by the movements of crusts, the building of mountains," Carlson told OurAmazingPlanet, "but this only occurred over a few thousand years and that's too short a time to be explained by tectonics."

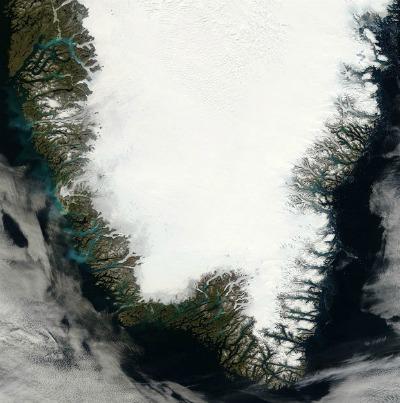

Greenland not guilty

It's fairly well-established that warmer temperatures contributed roughly 1.3 feet (.4 m) to those high ocean waters; water expands as it gets hotter. That leaves melting ice as the only remaining factor, and presented scientists with two main suspects.

"The only viable sources are Antarctica or Greenland," Carlson said. "When we first started this study, I actually thought you could explain most of the sea level rise from Greenland, and then we got these results."

Carlson and his colleagues studied silt that was deposited along the ocean floor during the Last Interglacial Period just south of Greenland. The silt was retrieved by a drilling expedition in 1999.

Isotopes - atomic signatures within the sediment - revealed where on Greenland the sediment originated; the presence or absence of sediment deposits themselves in certain spots beneath the ocean floor indicated if the island was ice-free or icebound during the Last Interglacial Period.

The research is some of the first to provide side-by-side geochemical and sedimentary evidence for the magnitude of ice loss on Greenland at the time. It indicates that on Greenland's southern half, ice indeed retreated 125,000 years ago, but not as much as many scientists estimated. "It's not what I expected," Carlson said.

Dodging a bullet

Good news? Not quite. It means that even the most conservative estimates of ancient sea height can't be explained by ice melt in the Northern Hemisphere alone.

"You need to have Antarctica retreating as well, which is more scary," Carlson said.

To the layman, prehistoric ice melt on a continent at the bottom of the world may not sound all that spooky, but worldwide climate may be well on its way to hitting the repeat button, scientists say.

"This is the most recent period when Northern Hemisphere summers were warmer than they are today, and it has been used as an analogy for what climate could be like at the end of the century," Carlson said.

He said more research is needed to better understand the details of climate 100,000 years ago in the Southern Hemisphere and the coinciding extent of ice melt on Antarctica, however, research does indicate Antarctica appears to be more prone to sudden, unpredictable melting than Greenland.

In fact, portions of Antarctica are already in the grip of pronounced temperature changes.

Research from the National Snow and Ice Data Center at the University of Colorado, Boulder, indicates that the Antarctic Peninsula, a finger of land that points toward South America, is one of the most swiftly warming areas on the planet.

In recent decades, the area has experienced catastrophic ice shelf collapses, which have been shown to speed the melt of glaciers.

Carlson said that although his research studies the far distant past, he does spend time thinking about what it means for the present.

"I think sea level rise is definitely worrisome," he said. The findings from this ancient period inform our understanding of what could happen to the icy island in today's warming world.

"It means Greenland is not as sensitive as people had previously thought," Carlson said. "So it will raise sea level in the future, but not as fast as people estimated."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter