An international team, including scientists at the Max Planck Institute in Germany, carried out a genetic study of a finger bone and a large molar tooth uncovered in Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains, Siberia. They sequenced the genome and found that this ancient human shared 4-6% of its genetic material with some present-day Melanesians.

In March, the team obtained a complete mitrochondrial DNA (mtDNA) sequence for the same finger bone, dated to about 40,000 years ago, showing that it was from neither a modern human nor Neanderthal.

Professor Chris Stringer, human origins expert at the Natural History Museum, comments on this research, 'The recovery of mtDNA from Denisova Cave was an exciting enough development, but this latest work by many of the same team is nothing short of sensational.

'This new work showed that the fossil finger bone female was actually slightly closer genetically to Neanderthals than to modern humans, but something else even more remarkable was revealed: the Denisovan is also related to one group of living humans - Melanesians, who live on some of the islands of south east Asia.'

Early modern humans interbred with Denisovans

'The most plausible explanation for this finding,' says Stringer, 'is that Denisovans were present further south as well as in Siberia, and pre-Melanesian [modern human] populations migrating from Africa through south east Asia must have interbred with some of these Denisovans, picking up an estimated 5% of their genes.'

Interbreeding with other human species

Modern humans (Homo sapiens) migrated out of Africa between 55,000-60,000 years ago. An intriguing question for scientists has been whether they interbred with other human species as they spread out around the rest of the world.

Last May, scientists obtained genetic evidence that showed that modern humans outside of Africa share genetic information with Neanderthals, Homo neanderthalensis, which suggests that they must have interbred (Neanderthals died out about 30,000 years ago). And now Denisova genes have also been added to the human genetic mix. But how much interbreeding went on?

Stringer says 'In terms of actual interbreeding events, on present data there might only have been two: one in the Middle East, perhaps 60,000 years ago, that input about 2.5% Neanderthal genes into recent humans outside Africa; and a subsequent one in south east Asia that added an additional 5% or so of Denisovan DNA into the ancestors of modern Melanesians.

'While these results do not challenge the notion that everyone alive today traces most of their genetic heritage to a recent African origin, as shown by our mitochondria, Y-chromosomes etc, when we get down to the fine resolution of the whole genome, the story has undoubtedly got a whole lot more complicated,' says Stringer.

Who are the Denisovans?

While modern humans left Africa about 60,000 years ago, there were also earlier human migrations, for example Homo erectus from about 1.75 million years ago.

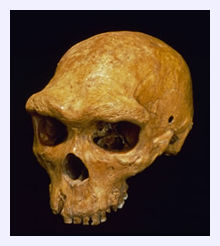

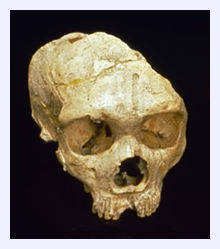

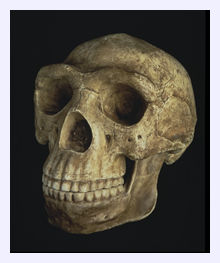

However, Stringer says that the Denisovan lineage probably evolved in parallel with those of Neanderthals and modern humans and after the research in March, he suggested it could have been an early off-shoot of Homo heidelbergensis (whose fossils are known from about 650,000 years ago).

This would also explain the mystery of some unidentified Asian skulls. 'There are various Asian fossils that have been difficult to classify from sites in India (Narmada) and China (for example Dali, Jinniushan),' says Stringer.

'They look different from H. erectus, but they also do not resemble Neanderthals or modern humans, and I have suggested some of them may be late-surviving examples of the species that gave rise to Neanderthals and H sapiens further to the west: H heidelbergensis. Following the first Denisova results, I speculated that this mtDNA might be from a late-surviving heidelbergensis living in Siberia.'

So, in Europe, H. heidelbergensis gave rise to Neanderthals, in Africa they gave rise to us, modern humans, and in Asia, perhaps to the Denisovans.

New questions

Stringer points out that this research raises many fundamental questions about human evolution past and present. Will scientists soon be able to match the Denisovan DNA with more complete human fossils, (such as the Asian fossil finds)? If they do, this will greatly clarify evolution in the region.

What function do the genes have?

And what function could the genes have? Stringer explains, 'As with the presence of small amounts of Neanderthal genes in some people today, there will now be considerable attention to what, if anything, those Denisovan genes might be doing in Melanesians. Are the genes functional, perhaps conferring resistance to disease or having some other effect on the biology of these populations today?

'There will also be a renewed focus on areas like Australia for signs of these genes, as this region has not yet been studied as part of the Denisova research.'

Is it time to reclassify humans?

Should we reclassify Homo sapiens and include ancient humans in the same group? For now, Stringer says no, as other closely related mammal species such as wolves and jackals, and bonobos and chimpanzees, can hybridise (produce viable offspring) too.

Stringer concludes, 'Personally I think that the distinctiveness and separate evolutionary histories of groups like Neanderthals and modern humans warrant their continuing recognition at the species level, provided we remember that this may not preclude some hybridisation.

'However, if genetic data eventually show that such interbreeding events were common and widespread then it will certainly be time to revisit the way we classify human species.'

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter